Introduction

Linux firewalls form the critical security perimeter of modern infrastructure, protecting servers, networks, and cloud environments from unauthorized access and malicious traffic. At the heart of this protection lies the Netfilter framework, a sophisticated kernel-level infrastructure that intercepts and processes network packets at strategic points in the networking stack. iptables, the user-space command-line utility, provides administrators with granular control over firewall policies, enabling the creation of stateful, rule-based security architectures. Understanding how these technologies work—their architecture, packet processing flow, connection tracking mechanisms, and practical applications—is essential for Linux security professionals, penetration testers, DevOps engineers, and system administrators responsible for network security. This article provides a comprehensive technical exploration of Netfilter and iptables, moving from foundational concepts through advanced configurations used in real-world scenarios.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this article, readers will understand:

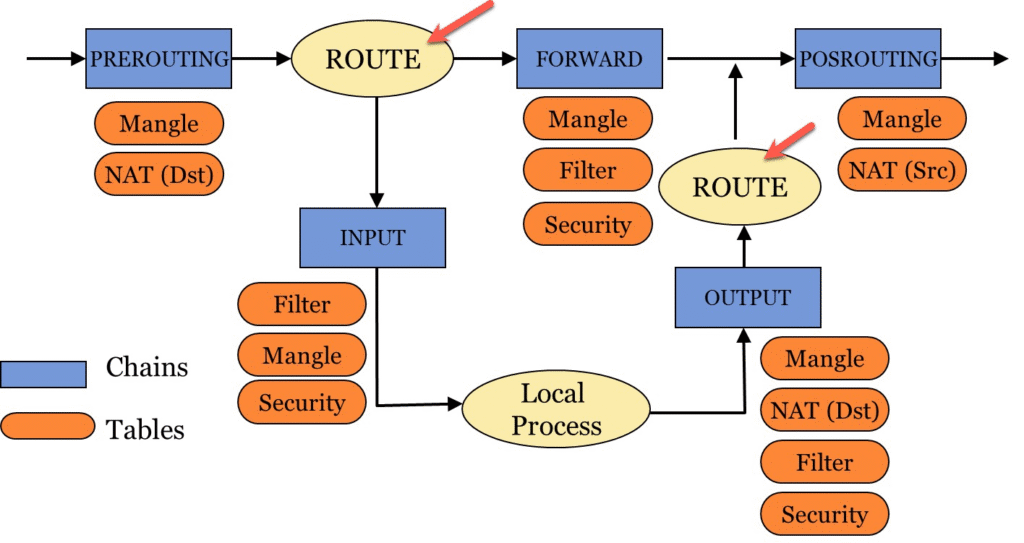

- The architectural foundation of the Netfilter framework and its five strategic packet processing hooks

- How iptables organizes firewall rules through tables and chains, and the hierarchical relationship between them

- The complete packet traversal flow for incoming, outgoing, and forwarded traffic through multiple tables and chains

- How connection tracking (conntrack) transforms iptables from a stateless packet filter into a sophisticated stateful firewall

- The purpose and functionality of each table—filter, nat, mangle, and raw—and their appropriate use cases

- How to implement advanced configurations including Network Address Translation (NAT), port forwarding, Quality of Service (QoS) marking, and SYN flood protection

- Practical debugging techniques, performance optimization strategies, and best practices for firewall design

- The transition from iptables to nftables and considerations for modern Linux deployments

What is the Netfilter Framework?

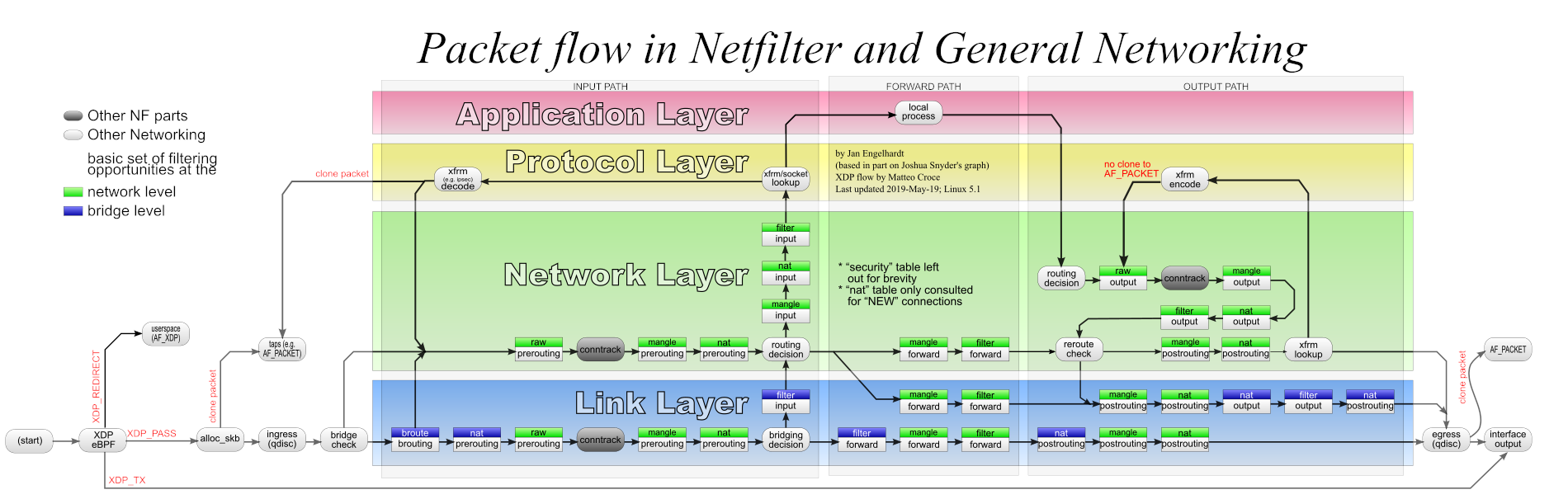

The Netfilter framework is a sophisticated kernel-level infrastructure integrated into the Linux kernel that provides packet filtering, network address translation, and stateful connection tracking capabilities. Rather than implementing firewalling as a monolithic kernel module, Netfilter uses a hook-based architecture that allows multiple kernel modules to register processing functions at strategic points where packets pass through the networking stack. This revolutionary design approach, developed and maintained by the Netfilter project, fundamentally changed how Linux systems handle network security by introducing a modular, extensible framework that doesn’t require constant kernel recompilation when firewall policies change.

The hook-based architecture represents a critical innovation in network packet processing because it decouples firewall policy from the core kernel networking code. Instead of embedding firewall logic directly in the network stack, Netfilter provides well-defined attachment points where external modules can inject processing logic. This separation of concerns enables administrators to load, unload, and modify firewall rules without recompiling the kernel, while simultaneously allowing multiple independent modules to process the same packet without interfering with each other. The framework became the de facto standard for Linux network security precisely because of this flexibility and modularity, enabling everything from simple packet filtering to complex network address translation and stateful connection tracking.

The Five Netfilter Hooks

Netfilter defines five primary hooks where network packets can be intercepted and processed. These hooks are strategically positioned at different stages of the packet’s journey through the Linux networking stack, each corresponding to a critical decision point in packet handling:

- NF_IP_PRE_ROUTING: Packets are intercepted immediately after arriving at the network interface, before any routing decision is made by the kernel. This hook processes incoming traffic at the earliest possible stage, before the kernel determines whether packets are destined for the local system, should be forwarded to another network, or should be rejected outright.

- NF_IP_LOCAL_IN: After the routing decision has been made and the kernel has confirmed that a packet is destined for the local system, packets reach this hook. This is where locally-delivered traffic is processed immediately after the routing engine accepts the packet but before it reaches the network applications listening on local ports.

- NF_IP_FORWARD: Packets that require forwarding through the system to reach a destination on a different network are processed at this hook. This is the critical point for implementing firewall policies on routers and gateways, where decisions must be made about whether traffic should be allowed to transit the system or should be blocked to prevent unauthorized network routing or data exfiltration.

- NF_IP_LOCAL_OUT: Packets generated by local processes and applications running on the system are processed at this hook before they undergo routing decisions and are sent to their destination networks. This allows filtering and modification of outbound traffic from the system itself, enabling administrators to control what data applications are allowed to send, prevent data exfiltration, or implement outbound access controls.

- NF_IP_POST_ROUTING: The final hook processes all traffic—both forwarded and locally-generated—after routing decisions have been made and before packets leave the system through network interfaces. This is where source network address translation (SNAT) and masquerading rules are applied, allowing multiple internal systems to appear as a single external IP address.

Hook Registration and Priority

Kernel modules register callback functions at each hook using priority numbers that determine the execution sequence. The kernel executes these callbacks in priority order, with lower numbers executing before higher numbers, enabling deterministic and predictable packet processing even when multiple kernel modules need to handle the same hook. This priority-based execution model is essential for maintaining consistent behavior in complex firewall configurations where packet filtering, connection tracking, NAT, logging, and other functions must all operate on the same packets in a specific order. The design allows firewall modules, logging modules, connection tracking modules, and NAT modules to coexist without interfering with each other’s functionality, each processing the packet in sequence and either passing it forward to the next module or terminating processing based on the module’s verdict.

The Netfilter Subsystems

Several core kernel subsystems operate through the Netfilter hooks, each providing distinct network security and manipulation capabilities:

- nf_conntrack: The connection tracking module that maintains detailed state information about network flows and conversations between systems. This subsystem transforms iptables from a simple stateless packet filter that evaluates each packet in isolation into a sophisticated stateful firewall that understands connection context and can make decisions based on whether a packet belongs to an established conversation, a new conversation attempt, or a related side-channel conversation like ICMP error messages.

- nf_nat: The Network Address Translation module providing both source network address translation (SNAT) and destination network address translation (DNAT) functionality. This subsystem allows systems to transparently modify packet headers while maintaining connection state, enabling applications to communicate with systems that appear to have different IP addresses than their actual addresses.

- nf_queue: An optional subsystem that allows user-space applications to process packets through the NFQUEUE target, enabling sophisticated inspection and decision-making outside the kernel. This capability is particularly valuable for implementing intrusion detection systems, complex content filtering, and custom packet processing logic that would be inefficient or inappropriate to implement as kernel modules.

- nf_log: The logging infrastructure that provides standardized packet logging and inspection capabilities, allowing administrators to record detailed information about packets matching specific criteria. This subsystem is essential for debugging firewall rules, forensic analysis of network traffic, and understanding packet flows during development and testing of firewall policies.

- nf_tables: The newer framework underlying nftables, representing the modern successor to the original iptables implementation. While iptables was historically the primary user-space interface to Netfilter, nftables provides a more efficient, unified, and elegant approach to firewall rule management with improved performance characteristics and support for more sophisticated data structures like sets and maps.

How iptables Processes Packets Works?

Tables and Chains Organization

iptables organizes firewall rules hierarchically into tables and chains, creating a sophisticated two-level categorization system that separates rules by both functional purpose and processing location within the packet’s journey. Each table serves a specific and distinct functional purpose and contains multiple chains that correspond directly to the netfilter hooks where rules are evaluated. This hierarchical organization allows administrators to understand and maintain complex firewall configurations by grouping related rules together—all rules affecting packet filtering can be found in the filter table, while all rules related to address translation can be found in the nat table. The relationship between tables and chains forms the architectural backbone of iptables, enabling both novice administrators to start with simple configurations and expert practitioners to build sophisticated, multi-layered security policies that operate across all stages of packet processing.

The Four Primary Tables

The iptables framework provides four distinct tables, each designed for a specific category of network operations, and understanding the proper use of each table is fundamental to writing effective and maintainable firewall policies:

- filter table: The default and most commonly used table in iptables, handling the fundamental access control decisions that form the core of firewall functionality. It contains only three chains: INPUT, FORWARD, and OUTPUT, corresponding to the primary packet flow paths. This table determines which packets are accepted to proceed to their destination, rejected with an error message sent back to the sender, or dropped silently without any notification.

- nat table: Dedicated to handling Network Address Translation operations, this table allows modification of both source and destination IP addresses while transparently maintaining connection state so that return traffic is correctly routed back. It contains four chains: PREROUTING for destination address translation before routing decisions, INPUT for address translation of locally-destined packets, OUTPUT for translation of locally-generated packets, and POSTROUTING for source address translation after routing.

- mangle table: Enables advanced packet manipulation operations beyond simple filtering, including header modification, Quality of Service (QoS) marking for traffic prioritization, packet marking for policy-based routing decisions, and manipulation of Time-To-Live (TTL) values. Unlike the filter and nat tables which focus on allowing or denying traffic, the mangle table allows modification of packet metadata and headers.

- raw table: Provides a specialized and narrow-focused mechanism to bypass the connection tracking system entirely for specific packets or protocols that would be inefficient or problematic if tracked. It contains only PREROUTING and OUTPUT chains and uses the NOTRACK target to explicitly exclude packets from the nf_conntrack connection tracking subsystem. The raw table is particularly valuable for protocols like IPSec that maintain their own connection state management or for high-performance scenarios where connection tracking overhead would create unacceptable latency or CPU usage.

Built-in Chains

Each chain corresponds directly to one of the five netfilter hooks, serving as the integration point where iptables rules are evaluated. Understanding the precise location and timing of each chain within packet processing is essential for writing rules that have the intended effect:

- PREROUTING: Processes packets immediately upon arrival at the network interface, before any routing decision is made by the kernel. This is the earliest point in packet processing where rules can be applied and is the mandatory location for destination NAT (DNAT) rules that must affect the routing decision.

- INPUT: Processes packets that have been determined by the routing engine to be destined for the local system, after PREROUTING processing but before the packets reach local applications and services. This chain is where administrators implement access controls for incoming connections to local services.

- FORWARD: Processes packets that have been determined by the routing engine to need forwarding to other networks, allowing administrators to control which traffic is allowed to transit the system. This chain is essential on systems acting as routers or gateways.

- OUTPUT: Processes packets that have been generated by local processes and applications running on the system, before those packets undergo routing decisions. This chain enables administrators to control what traffic local applications are allowed to send and prevents compromised applications from making unauthorized outbound connections.

- POSTROUTING: Processes all traffic—both forwarded and locally-generated—after routing decisions have been finalized and immediately before packets leave the system through network interfaces. This is where source NAT (SNAT) and masquerading rules must be located to affect all outbound traffic.

Packet Traversal Through Chains and Tables

Understanding packet flow through the complete iptables framework is absolutely fundamental to writing effective firewall rules that produce the intended results. The kernel processes packets through tables in a strictly enforced and invariant specific order that never changes: raw → mangle → nat → filter. This ordering is critical because it ensures that connection tracking bypass decisions (raw table) occur before connection tracking happens, packet marking (mangle table) occurs before routing decisions that depend on those marks (nat and filter), and finally the definitive allow/deny decision (filter table) occurs last after all other processing. Deviating from this understanding or attempting to apply rules in the wrong table will result in rules that have no effect or unexpected behavior.

Incoming Packet Processing

When an external host sends a packet to the system destined for a local service or forwarded through the system to another network, the packet undergoes a complex series of processing stages across multiple tables and chains. Understanding this complete flow is essential for predicting how firewall rules will behave:

- The packet arrives at the network interface from the external network and immediately enters the PREROUTING hook, the earliest point in the packet processing pipeline.

- The raw table PREROUTING chain rules are evaluated first, allowing administrators to make decisions about connection tracking bypass using the NOTRACK target before any connection tracking occurs.

- The mangle table PREROUTING chain rules are evaluated next, allowing modification of packet metadata, TTL values, and packet marking that might affect subsequent routing or NAT decisions.

- The nat table PREROUTING chain rules are evaluated, where destination NAT (DNAT) translations occur to rewrite the destination IP address before the routing engine makes its forwarding decision based on the translated address.

- The kernel’s routing engine makes a critical routing decision: should this packet be delivered to a local process on this system, or should it be forwarded to another network? This decision is based on the packet’s destination address (which may have been modified by DNAT in the previous step) and the system’s routing table.

- If the routing decision determines the packet is destined locally, the packet enters the INPUT hook and the filter table INPUT chain rules are evaluated, where the firewall’s primary access control policy is enforced.

- If all filter table INPUT chain rules pass and no rule drops or rejects the packet, the packet reaches the local application listening on the destination port and is processed by the application.

- If the routing decision determined the packet should be forwarded to another network, the packet enters the FORWARD hook and the filter table FORWARD chain rules are evaluated, allowing the firewall to control which traffic is permitted to transit the system.

- Regardless of whether the packet was destined locally or forwarded, the packet reaches the POSTROUTING hook where the mangle table POSTROUTING chain rules are evaluated first, allowing final packet modifications.

- The nat table POSTROUTING chain rules are evaluated, where source NAT (SNAT) and masquerading rules translate the packet’s source address to implement network address translation scenarios.

- Finally, the packet leaves through the appropriate outbound network interface on its journey toward the destination.

Outgoing Packet Processing

When a local process or application running on the system generates network traffic and sends it to a destination on another network, the outgoing packet must traverse a similar but distinct processing path through the iptables framework:

- The packet is generated by the local application or process and immediately enters the OUTPUT hook, representing the earliest point in the outbound packet processing pipeline.

- The raw table OUTPUT chain rules are evaluated first, allowing decisions about whether this packet should bypass connection tracking using the NOTRACK target.

- The mangle table OUTPUT chain rules are evaluated next, allowing modification of outbound packet metadata, TTL values, and DSCP values for quality of service prioritization.

- The nat table OUTPUT chain rules are evaluated, allowing modification of the packet’s destination address (destination NAT) before the routing engine processes it. This is less common than PREROUTING DNAT but is essential for certain scenarios.

- The kernel’s routing engine makes the routing decision determining which network interface the packet should leave through, based on the destination address (possibly modified by OUTPUT chain DNAT rules) and the system’s routing table.

- The filter table OUTPUT chain rules are evaluated, where access control policies for outbound traffic can be implemented. Importantly, the filter table INPUT policy does NOT apply to locally generated outbound traffic—the OUTPUT chain is specifically used for this purpose, and administrators must explicitly create OUTPUT rules to control local application behavior.

- The mangle table POSTROUTING chain rules are evaluated, allowing final packet modifications after the routing decision.

- The nat table POSTROUTING chain rules are evaluated, where source NAT (SNAT) and masquerading rules translate the packet’s source address if needed. This ensures that the packet appears to come from the gateway system’s IP address rather than the internal system’s IP address.

- Finally, the packet leaves through the appropriate outbound network interface toward its destination, completing the outbound packet processing pipeline.

Connection Tracking and Stateful Filtering

Connection tracking is an exceptionally sophisticated kernel subsystem that fundamentally transforms iptables from a simple, stateless packet filter that evaluates each packet in complete isolation into a powerful stateful firewall that maintains contextual information about network conversations and can make decisions based on connection context rather than individual packet characteristics. The nf_conntrack kernel module maintains detailed state information about all active network flows, tracking which packets belong to which connections and remembering whether a connection is in its initial setup phase, actively exchanging data, or in process of termination. This stateful approach enables firewall administrators to write policies that are far more intuitive and secure than stateless filtering would allow, as administrators can write a single rule accepting “established connections from anywhere” rather than enumerating all valid response traffic patterns for each service.

Connection tracking assigns each packet to one of several distinct states that reflect the packet’s relationship to known connections:

- NEW: The first packet of a connection that the connection tracking system has never seen before, typically exemplified by a TCP SYN packet initiating a new connection. The system has no prior record of this connection in its connection tracking table.

- ESTABLISHED: Packets belonging to a confirmed, bidirectional connection where data has been successfully exchanged in both directions and the connection is actively operational. These packets are guaranteed to be legitimate replies to traffic initiated by the local system.

- RELATED: Packets that are logically associated with an existing connection but are not direct replies to the original request, such as ICMP error messages generated in response to packets in an existing connection, or data channel connections in protocols like FTP where the control connection initiates data channel connections. These packets are permitted because they are legitimately associated with authorized connections.

- INVALID: Packets that the connection tracking system cannot classify into any valid state, indicating that they are malformed, violate protocol specifications, or appear to be attack attempts. These packets typically indicate protocol violations or potentially malicious traffic and should almost always be dropped.

- UNTRACKED: Packets that have been explicitly excluded from connection tracking through the raw table’s NOTRACK target. These packets bypass all connection tracking overhead and are evaluated only by stateless rules.

Connection tracking enables remarkably powerful and elegant stateful rules. The following single rule accepts all return traffic from connections initiated by local processes, dramatically simplifying firewall policy and reducing the number of explicit rules required:

iptables -A INPUT -m conntrack --ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPTThis rule leverages connection tracking to automatically accept any packets belonging to connections that the local system initiated or related to those connections, while still requiring explicit rules for new incoming connections initiated by external systems.

Rule Matching and Actions

Each iptables rule consists of two fundamental components: matching criteria that determine which packets the rule applies to, and an action (called a “target”) that determines what happens to packets matching those criteria. The kernel evaluates rules sequentially within a chain, examining packets against each rule in order until finding a matching rule that specifies an action. Once a match is found, the kernel takes the specified action and does not evaluate any subsequent rules in that chain (unless the action is LOG, which does not terminate rule evaluation). If the kernel evaluates all rules in a chain without finding a match, the chain’s default policy is applied, typically either DROP (deny the packet) or ACCEPT (allow the packet to proceed).

The most commonly used targets that determine what happens to matching packets are:

- ACCEPT: Allow the packet to proceed to the next stage of processing or to the destination application, permitting the network traffic to complete successfully.

- DROP: Silently discard the packet without sending any notification to the sender, allowing the connection attempt to simply time out. This is often preferred over REJECT for security reasons as it provides no information to potential attackers.

- REJECT: Discard the packet and send an error message (typically an ICMP destination unreachable message or TCP reset) back to the sender, informing them that the connection was refused. This provides explicit feedback but reveals that the system exists and is filtering traffic.

- LOG: Log detailed information about the packet to the system logs without affecting whether the packet is accepted, rejected, or dropped. The LOG action allows continuation to the next rule, enabling logging without terminating rule evaluation.

- MARK: Mark the packet with metadata for use in quality of service (QoS) decisions or policy-based routing, allowing the packet to be handled differently by network queues or routing engines based on the mark value.

- SNAT/DNAT: Translate the packet’s source or destination IP address, modifying the packet’s header to implement network address translation. These actions are only valid in the nat table.

- NFQUEUE: Send the packet to a user-space application for processing through the netfilter queue mechanism, allowing sophisticated application-level inspection and decision-making outside the kernel.

- NOTRACK: Exclude the packet from the connection tracking system entirely, bypassing all connection state tracking overhead. This action is only valid in the raw table and is used for protocols that maintain their own state management.

If no rule within a chain matches a packet, the kernel applies the chain’s default policy, which is typically DROP (deny by default) for the INPUT and FORWARD chains for security, and ACCEPT for the OUTPUT chain to allow local applications to communicate. Additionally, administrators can create custom chains that are not built-in hooks but are referenced from built-in chains, allowing the creation of reusable rule groups and more maintainable firewall configurations.

Common and Advanced Use Cases and Configurations

github.com/HalilDeniz: Bash Script for Managing iptables Rules

Basic Stateful Firewall Configuration

Establishing a robust security posture with iptables typically begins with a default-deny approach, in which all traffic is denied unless specifically permitted by an explicit rule. This configuration sets the baseline by enforcing strict policies that only allow traffic deemed safe by the administrator while blocking all other connections. Such an implementation is considered a fundamental best practice and dramatically reduces the system’7s exposure to unsolicited or potentially malicious traffic. By starting with a DROP policy on the INPUT and FORWARD chains and only permitting critical services such as loopback communications, ongoing connections, essential administrative protocols like SSH, and common web services, administrators create a controlled environment that is resistant to the majority of unsophisticated attack vectors.

This principle of minimal exposure means the firewall accepts only the traffic vital for system operation, like the loopback interface, and uses connection tracking to facilitate seamless communication for packets belonging to established or related connections. This approach allows network services and users to maintain ongoing sessions without interruption while ensuring that new, unauthorized access attempts are blocked unless an administrator has expressly allowed them. The overall process streamlines rule management and monitoring, increases clarity in audits, and simplifies troubleshooting for legitimate traffic.

A fundamental security posture implements default-deny policies with explicit allow rules:

# Set default policies to DROP

iptables -P INPUT DROP

iptables -P FORWARD DROP

iptables -P OUTPUT ACCEPT

# Allow loopback traffic (required for system functionality)

iptables -A INPUT -i lo -j ACCEPT

iptables -A OUTPUT -o lo -j ACCEPT

# Allow established and related connections

iptables -A INPUT -m conntrack --ctstate RELATED,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

# Allow SSH from administrative network

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 22 -s 192.168.1.0/24 -j ACCEPT

# Allow HTTP and HTTPS

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 80 -j ACCEPT

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 443 -j ACCEPT

# Drop everything else (implicit by policy)Network Address Translation and Port Forwarding

Network Address Translation (NAT) serves as a potent mechanism for obscuring the internals of complex networks. It enables multiple devices within a private network to communicate with external networks using a common public IP address while maintaining session integrity and seamless bidirectional communication. Source NAT (SNAT) is generally employed to mask internal addresses during outbound connections, providing anonymity and easy management for environments where client IPs may change frequently, such as corporate offices and home networks with DHCP-assigned addresses.

Destination NAT (DNAT), on the other hand, is foundational for implementing port forwarding and enabling external access to internal services. By rewriting the destination address of arriving packets, DNAT helps to transparently relay traffic from outside the firewall to servers and services hidden within the protected network. This combination of NAT techniques not only facilitates scenarios like remote web or SSH access to internal machines but also supports advanced architectures including load balancing and multi-tier application deployments where multiple servers share public-facing responsibilities without exposing their private addresses directly to the internet.

Source NAT (SNAT) masks internal IP addresses when traffic exits:

# Masquerade all internal traffic through eth0

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o eth0 -j MASQUERADE

# Fixed source address translation

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o eth0 -j SNAT --to 203.0.113.50Destination NAT (DNAT) implements port forwarding:

# Forward external port 8080 to internal web server

iptables -t nat -A PREROUTING -i eth0 -p tcp --dport 8080 -j DNAT --to-destination 192.168.1.100:80

# Corresponding filter rule to allow the forwarded traffic

iptables -A FORWARD -i eth0 -d 192.168.1.100 -p tcp --dport 80 -j ACCEPT

iptables -A FORWARD -i eth1 -s 192.168.1.100 -p tcp --sport 80 -j ACCEPTQuality of Service and Traffic Marking

Advanced security and network management often involve prioritizing certain types of traffic or ensuring that bandwidth-consuming data flows do not degrade the quality of essential services. The mangle table empowers network administrators to manipulate traffic at the packet level by marking packets for high-priority processing or adjusting header values that influence how routers and switches treat these packets through core networks. Marking packets from specific subnets can establish policies for fast-lane routing or ensure that voice, video, and other real-time communications maintain acceptable performance levels even during periods of congestion.

Leveraging DSCP and QoS markings directly in iptables rules ensures that mission-critical flows, such as those required for VoIP or latency-sensitive applications, retain preferential treatment end-to-end, while bulk data transfers and peer-to-peer traffic can be deprioritized, preserving bandwidth and service integrity for business-critical communications. Such granular control is especially relevant in multi-tenant cloud and enterprise settings where resource contention is frequent and quality of service differentiation is necessary.

The mangle table enables QoS through packet marking and DSCP modifications:

# Mark packets from specific subnet for priority routing

iptables -t mangle -A PREROUTING -s 192.168.1.0/24 -j MARK --set-mark 0x10

# Prioritize VOIP traffic via DSCP

iptables -t mangle -A POSTROUTING -p udp --dport 5060 -j DSCP --set-dscp 46

# Deprioritize bulk transfers

iptables -t mangle -A POSTROUTING -p tcp --dport 6881:6889 -j DSCP --set-dscp-class cs1SYN Flood Protection with SYNPROXY

Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks leveraging TCP SYN floods can quickly overwhelm a server, exhausting its connection table and rendering legitimate services unreachable. The SYNPROXY target in iptables functions as a highly specialized mitigation technique by intercepting SYN packets and completing the handshake independently, serving as a proxy for the backend server. Only genuine connection attempts that successfully complete the handshake are relayed to the application, while incomplete SYN flood packets are dropped, greatly reducing the likelihood that attackers can overwhelm server resources.

Configuring SYNPROXY requires integration with both conntrack and raw tables, along with careful tuning of kernel parameters to enforce strict state validation. This multilayered defense strategy not only blocks large-scale, automated attack traffic but also preserves service availability and reduces noise that can interfere with routine network operations. SYNPROXY is especially effective for protecting publicly accessible services like web and mail servers that are more likely to be targeted in volumetric DDoS campaigns.

SYNPROXY mitigates SYN floods by acting as a TCP proxy, preventing connection exhaustion:

# Mark SYN packets for special handling in raw table

iptables -t raw -I PREROUTING -i eth0 -p tcp --syn --dport 80 -j CT --notrack

# Enable strict conntrack for marked invalid packets

sysctl -w net/netfilter/nf_conntrack_tcp_loose=0

# Apply SYNPROXY to protected traffic

iptables -A INPUT -i eth0 -p tcp --dport 80 -m state --state INVALID,UNTRACKED -j SYNPROXY --sack-perm --timestamp --wscale 7 --mss 1460

# Drop remaining invalid packets

iptables -A INPUT -m state --state INVALID -j DROP

# Enable TCP timestamps for SYN cookies

sysctl -w net/ipv4/tcp_timestamps=1Rate Limiting and Connection Limits

Controlling the rate at which connections are initiated and managed is vital for defending against brute force attacks, credential stuffing, or aggressive network scans. Iptables offers rich modules such as limit, hashlimit, and connlimit, each designed for a different aspect of traffic metering. Simple rate limiting can cap the absolute number of packets accepted per minute, thwarting unintentional log flooding and curbing resource exhaustion due to abnormal client behavior.

More granular enforcement can be achieved through hashlimit, ensuring that individual IP addresses, users, or services cannot exceed configurable thresholds of connection or request rates, while connlimit allows setting hard upper bounds on the simultaneous connections from a source IP. These techniques empower administrators to maintain stable service levels and block abusive clients while still supporting legitimate users and sessions without compromise or unnecessary service downtime.

Protect services from abuse through rate limiting and per-source connection limits:

# Simple rate limiting (5 packets per minute)

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 80 -m limit --limit 5/m --limit-burst 10 -j ACCEPT

# Per-source hashlimit (10 connections per second per IP)

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 80 -m hashlimit --hashlimit 10/sec --hashlimit-mode srcip --hashlimit-name http -j ACCEPT

# Reject sources exceeding 80 concurrent connections

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 80 -m connlimit --connlimit-above 80 -j REJECT --reject-with tcp-resetAdvanced Matching: String Inspection

Deep packet inspection through iptables’ 27 string module addresses the need to block high-risk payloads, such as requests containing known malware signatures or DNS queries for black listed domains. When conventional header-based matching falls short, string inspection delves into the actual packet content to instantly identify and block flows associated with malicious activity, phishing attempts, or data leaks.

By leveraging algorithms like Boyer-Moore (bm) and Knuth-Morris-Pratt (kmp), iptables rules can efficiently scan payloads for specific patterns without causing undue performance issues, making string inspection a practical line of defense in security-conscious environments where traditional firewalling alone may leave gaps in protection.

The string module enables payload-level inspection:

# Block HTTP requests containing malware signatures

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 80 -m string --algo bm --string "malware_signature" -j DROP

# Block DNS queries for known malicious domains

iptables -A OUTPUT -p udp --dport 53 -m string --algo kmp --string "malicious.domain" -j DROPTCP Flag Matching for Protocol Anomalies

Detecting anomalous packet structures—such as those utilized in network reconnaissance or probing—requires monitoring not only connection states but also the specific combinations of TCP flags set within each frame. Iptables provides fine-grained matching for SYN, FIN, and other flag combinations to mitigate common scanning tactics including Xmas and Null scans.

Such detailed anomaly detection and filtering capabilities help network operators identify and proactively block packets characteristic of penetration tests or pre-attack reconnaissance, significantly reducing surface area and alerting administrators to ongoing suspicious activities targeting critical infrastructure components. Blocking nonstandard flag combinations is a proven technique for raising the bar and deterring low-effort intrusion attempts.

Detect and block suspicious TCP combinations:

# Drop packets with SYN and FIN flags (port scanning/network reconnaissance)

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --tcp-flags SYN,FIN SYN,FIN -j DROP

# Drop packets with all flags set (Xmas scan)

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --tcp-flags ALL ALL -j DROP

# Drop packets with no flags set (Null scan)

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --tcp-flags ALL NONE -j DROP

# Drop TCP packets that lack the ACK flag in response sequences

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp ! --tcp-flags ACK ACK -m conntrack --ctstate NEW -j DROPLogging with Rate Limiting

Logging is a double-edged sword in firewall management: while it offers valuable insight into ongoing network activity and policy effectiveness, excessive or unregulated logging risks overwhelming system resources or obscuring useful information amidst a flood of benign events. dedicating a dedicated logging chain in iptables, complemented by targeted use of the limit module, ensures that only important events are recorded at digestible rates.

Structured syslog entries with context-rich prefixes facilitate rapid correlation and incident response, while log chains provide flexible points of inspection that administrators can update in real-time as new threats or auditing requirements arise. Careful configuration of logging rules helps maintain system performance while supporting compliance, forensic analysis, and proactive threat mitigation efforts.

Logging without rate limiting can overwhelm system resources:

# Create dedicated logging chain

iptables -N logdrop

iptables -A logdrop -m limit --limit 5/m --limit-burst 10 -j LOG --log-level info --log-prefix "DROPPED: "

iptables -A logdrop -j DROP

# Use the logging chain in rules

iptables -A INPUT -i eth0 -p tcp --dport 1234 -j logdropNFQUEUE for User-Space Processing

NFQUEUE stands out as a specialized target for advanced scenarios that require user-space packet processing, such as custom intrusion detection and prevention systems (IDS/IPS), real-time network manipulation tools, or complex policy engines. By delegating selected traffic to applications via libnetfilter_queue, administrators can inject rich context and application logic into firewall workflows, extending decision power beyond kernel modules.

Queue balancing and round-robin distribution to multiple parallel user-space handlers allow for scalable, high-throughput implementations that meet the needs of contemporary enterprise, cloud, and carrier operations, supplementing the core firewall framework with bespoke capabilities and adaptive response mechanisms.

Delegate complex packet decisions to user-space applications:

# Send suspicious traffic to user-space IDS

iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 80 -j NFQUEUE --queue-num 0

# Distribute across multiple queues for parallel processing

iptables -A FORWARD -j NFQUEUE --queue-balance 0:3Kernel Connection Tracking Optimization

High-performance and high-availability environments with immense connection loads, such as web hosting platforms and cloud datacenters, often require careful tuning of connection tracking tables and kernel parameters to avoid resource exhaustion and unintended service interruptions. Increasing maximum connection tracking entries, reducing TCP FIN_WAIT and TIME_WAIT timeouts, and periodically recalibrating bucket allocations help maintain responsiveness and ensure stability under volatile or unexpected workloads.

Making these changes persistent through sysctl.conf and monitoring their effects over time supports proactive scalability planning, resilient service delivery, and prompt adaptation to changing business requirements, traffic patterns, and security postures.

For high-traffic systems, tune connection tracking parameters:

# Increase maximum tracked connections

sysctl -w net.netfilter.nf_conntrack_max=1048576

sysctl -w net.netfilter.nf_conntrack_buckets=1048576

# Reduce timeout for FIN_WAIT state (from 120 to 30 seconds)

sysctl -w net.netfilter.nf_conntrack_tcp_timeout_fin_wait=30

# Reduce timeout for TIME_WAIT state

sysctl -w net.netfilter.nf_conntrack_tcp_timeout_time_wait=30

# Make changes permanent

echo "net.netfilter.nf_conntrack_max = 1048576" >> /etc/sysctl.conf

echo "net.netfilter.nf_conntrack_buckets = 1048576" >> /etc/sysctl.confDebugging Firewall Rules with TRACE

Firewall debugging represents a unique challenge given the complexity and dynamism of packet processing workflows. The TRACE target in iptables arms administrators with deep visibility into every step a packet takes through chains and tables. By enabling granular tracing for specific flows, such as ICMP packets or critical service ports, and correlating kernel log messages with operational timelines, it becomes possible to pinpoint rule-matching behavior and swiftly identify errors, omissions, or unexpected consequences in complex rule sets.

Combining trace outputs with real-time log analysis tools and proactive auditing routines ensures that misconfigurations are detected early and quickly resolved, optimizing performance and reliability without compromising security.

The TRACE target reveals exact packet processing paths through tables and chains:

# Enable tracing for ICMP packets

iptables -t raw -I OUTPUT -p icmp -j TRACE

# View kernel logs showing packet traversal

dmesg | grep TRACE

# Check system log directly

tail -f /var/log/syslog | grep TRACEOutput appears as: TRACE: filter:INPUT:policy:ACCEPT rulenum=5

Inspecting Rule Counters and Statistics

Rule counters and byte statistics are indispensable for tracking the effectiveness of security policies. Monitoring these metrics provides insight into usage patterns, identifies misapplied or redundant rules, and supports data-driven tuning of firewall configurations. Regular viewing and resetting of counters simplifies iterative development, precision troubleshooting, and compliance reporting, allowing for the continuous improvement of security postures based on actual network activity.

Monitor rule effectiveness through packet and byte counters:

# Display rules with hit counters

iptables -L -v -n

# Reset counters

iptables -Z

# Export rules with counters in machine-readable format

iptables-save -cConclusion

The Netfilter framework and iptables represent a mature, production-proven approach to Linux network security. Their hook-based architecture, combined with sophisticated connection tracking, enables the creation of stateful firewalls that protect modern infrastructure from unauthorized access, DDoS attacks, and malicious traffic patterns. Understanding the five netfilter hooks, the organization of tables and chains, the complete packet traversal flow, and the nuances of connection tracking provides the foundation for implementing robust security architectures. From basic stateful filtering through advanced configurations including Network Address Translation, Quality of Service marking, SYN flood mitigation, and rate limiting, iptables scales from small embedded systems to large-scale data center deployments. Practical mastery requires not only knowledge of rule syntax but also understanding packet flow, debugging techniques, performance optimization, and security implications. While nftables represents the modern successor with improved performance and unified syntax, iptables remains widely deployed across production systems and continues to be the de facto standard for Linux firewall administration. For security professionals, penetration testers, and system administrators responsible for infrastructure protection, deep expertise in netfilter and iptables is essential knowledge that forms the foundation for advanced network security practices, incident response operations, and infrastructure hardening initiatives.

By combining foundational understanding with hands-on practice configuring rules, debugging packet flows, and optimizing performance, practitioners develop the expertise to build firewalls that serve as effective security perimeters while maintaining system performance and availability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

A: DROP silently discards packets without notifying the sender, causing connection attempts to timeout without any feedback. This provides minimal information to attackers about whether the system is filtering traffic. REJECT sends an explicit error message back to the sender (typically ICMP destination unreachable or TCP reset), which is more informative for legitimate users but reveals that the system exists and is filtering. Use DROP for external threats and unknown attackers, while REJECT may be appropriate for administrative access policies where providing explicit feedback improves user experience.

Connection tracking enables stateful firewalling where administrators write a single rule accepting “established and related connections” instead of creating complex rules for every valid response pattern. In stateless filtering, every packet must be evaluated against the entire rule set independently. Connection tracking reduces rule complexity, improves performance by allowing quick decisions for return traffic, and provides better security by distinguishing between legitimate responses to outgoing requests and unsolicited incoming traffic. This makes the firewall more efficient and easier to manage.

The raw table allows excluding specific packets from connection tracking using the NOTRACK target. This is useful for protocols like IPSec that maintain their own state management, making connection tracking overhead unnecessary. In high-performance scenarios processing millions of packets per second, bypassing connection tracking reduces CPU consumption and latency for specific traffic flows. Using the raw table to NOTRACK non-critical traffic allows administrators to optimize firewall performance while maintaining full connection tracking for traffic that benefits from it.

Use iptables-save and iptables-restore utilities to export and restore firewall rules. Execute iptables-save > /etc/iptables/rules.v4 to save current rules, then configure your system to run iptables-restore < /etc/iptables/rules.v4 at boot time. Most distributions provide convenience packages like iptables-persistent that automate this process. For IPv6, use ip6tables-save and ip6tables-restore, or use modern systemd units that handle both IPv4 and IPv6 persistence automatically.

Yes, rule evaluation imposes performance overhead. Optimize by ordering rules by frequency of matching (most-matched rules first), tuning connection tracking parameters (increasing nf_conntrack_max and nf_conntrack_buckets), reducing TCP timeout values, and using the raw table to bypass connection tracking for non-critical traffic. For extremely high-traffic scenarios, nftables provides more efficient algorithmic properties with sets and maps that process thousands of rules more efficiently than iptables’ linear evaluation.

Create a safety mechanism to automatically flush rules after a timeout period using at scheduling. Use INSERT (-I) instead of APPEND (-A) to place test rules at the beginning of chains where they execute first. Enable the TRACE target in the raw table to see exactly which rules packets match and their path through tables and chains. Test on isolated systems or virtual machines first, and use iptables -L -v -n to identify rule hit counts and identify ineffective rules before deployment.

nftables is the modern successor to iptables with significant improvements: unified syntax consolidates iptables, ip6tables, arptables, and ebtables into one framework; improved performance through efficient data structures like sets and maps; atomic updates prevent partially-applied configurations. However, nftables adoption requires ecosystem migration. For new projects on modern Linux systems (kernel 3.13+), nftables is strongly recommended. Use iptables-translate to convert existing rules. For legacy environments with extensive iptables expertise, continuing with iptables remains viable but nftables represents the future direction

References: